Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Alarm. Hour 3500.

By Hour 3500 of The Deluge, the murky water had reached the topmost step of Flory’s porch. It seemed a strange signifier of time having passed, in a grey world of incessant rain. The local authorities had set up a blaring alarm that announced what hour of the Downpour, and now the Deluge, we were in— an odd exercise in timekeeping, fruitless in the face of the ceaseless monsoon.

The Downpour had signalled the end of Flory’s morning ritual, the endless rain disintegrating the breadcrumbs left out for birds that no longer seemed to exist. Flory still sang in the morning. I would see her pottering about her wild little garden, lips moving– almost like she was speaking to the plants. I could hear nothing but the sound of the torrential rain. I was terrified of the weather, and the weather was constant, so I was constantly terrified.

Most days, I found myself feeling alone, and helpless, and angry– with nothing to do, nothing that could be done. I would sit for hours, days, 500 alarms (Who even knew anymore?) watching Flory’s forest from my window.

It had thrived when the rains came, if only for a while. In the 100th hour of The Downpour (which seems an entire distressing eternity ago now), a swift, dark, buzzing cloud marked the exodus of the bees from the beehive. In the 300th hour, the branch holding the empty hive, bereft of its inhabitants, crashed through the undergrowth, taking several of the tiles from her roof with it. Flory’s songs had grown wistful, a hoarse whisper barely escaping as she craned her neck to squint through the rain at the grey sky, no longer hidden by the intricate canopy of her once thriving garden. She had worn black since the day the beehive fell, and the rumours of witchcraft had only grown louder and more venomous.

By the time The Deluge was upon us, the forest looked like a swamp. The rain, when it fell in The Downpour, was clear, but the floodwater of the Deluge was like murky blood, thick with the red soil of the land.

Flory’s forest had died, the salinity of the floodwater choking the last of her garden plants around the 600th hour of The Deluge. I wondered what would happen to Flory now, a concern not wholly unselfish – what would I do now?

Flory proved resilient, and within weeks her home had transformed into a new kind of forest. Earthen pots, darkened with moisture and speckled with salt, lined Flory’s partly submerged porch wall, with strange waxy plants peeking out. Dark green seaweed hung from the wall, and swayed in the saline stream below. Old empty jars with rusty lids and muddy contents sat haphazardly on the windowsills, herbariums with saplings so small, I couldn’t recognize what they were. Then, in the 800th hour of the Deluge, I watched Flory gently transplant the saplings into a row of partly submerged pots in the flooded garden. Mangroves. Bonsai mangroves with small, stilted roots– when Flory glanced hopefully up at the dark clouds, I wondered if she saw me, smiling for the first time in 800 hours, at a freshly planted row of stunted trees.

Alarm. Hour 3999.

Around the time the beehive had fallen, someone had spray painted the word ‘WITCHRAFT’ in gaudy neon yellow across Flory’s porch wall. I had wondered, the day it appeared, if the spelling mistake was intentional, or an accident resulting from hurried vandalism, children scared of being caught by someone they seemed to think was a witch. It bothered me either way, but not as much as the fact that Flory had never painted over it, or tried to clean it off.

It is the 4000th hour of The Deluge, and the paint has finally begun to run. Flory is sitting on her porch, bare feet in the water, talking to the mangroves, with the word ‘WITCHRAFT’ dripping down the wall behind her.

Alarm. Pause.

“Hour 4000 of The Deluge.”

Pause.

Alarm.

Again?

“In the 4040th hour, the evacuation boats will be arriving in your area to take you to the Afterlife. Please carry government issued identification. Do not pack anything. Be prepared to leave by the 4040th hour. Help is on its way. Thank you.”

Help is on its way. I test the phrase in my mouth.

A sudden unease in my stomach forces me to sit down. What’s the point? What had survived The Deluge anyway? What would this new world, the AfterLife, look like? What would I do there? What if –

Fighting the spreading anxiety, I desperately turned to look at Flory, still sitting on her porch, feet in the water. She seems unaffected by the unexpected announcement. My dread turns to frustration, and prompts me to walk towards my front door. I pull on my gumboots, untouched since the early days of The Downpour, and find myself making my way through the murky water towards Flory’s house.

I push open the gate, rusted to near immobility by moisture and disuse. Something bumps against my toe, and nips it. Startled, I glance down to see a tiny fish nibbling at the edge of my foot.

Fish… Wait. Fish?! Not since the early days of The Deluge…

“How?” I gasp aloud.

“The plants.”

The voice above me momentarily shifts my attention away from the wondrous little creature at my foot. Flory steps off her porch and into the flooded garden. The lace hem of her black dress swirls in the water at her calves, as she wades effortlessly through the water.

“They come because of the plants. They are because of the plants,” she offers by way of explanation.

I nod silently, unsure what to do besides watch the fish.

“Let it feed,” she smiles, “Got all this extra skin, without much use for it anyway.”

I find myself nodding solemnly as I look back up at her face smiling back at me. I walk toward her, letting the fish trail along with me, occasionally getting a nibble at my heels.

“I don’t know if you heard,” I say, “The rescue boats are coming to take us to The Afterlife.”

Flory chuckles softly, and I realise I like the calm amusement in her laugh – “How could I not? They blast that bloody alarm every hour, like the passage of time means anything without the setting sun, or migrating ibises, or falling leaves…”

Alarm. As if on cue.

Her voice trails off, but I almost feel the grief in her voice settle softly in the water around us, sending ripples to the edges of the garden.

“Maybe people would be less mean if you didn’t do things like sing to plants, and grow seaweed from your window panes.”

“Maybe people would be less mean if they sang to plants and grew seaweed from their window panes too.”

“What do you even talk to plants about?”

“The weather.” Flory grins, and I can’t help but smile back.

“Plants love singing, that’s why the birds did it, the bees did it, and when the cicadas emerged – they sang to the trees too. Remember how noisy the squirrels used to be?”

I feel oddly satisfied with this answer, this shared memory of the sounds of our home keeping time. I find myself wanting her to come to the AfterLife, with her strange plants and reassuring answers.

“Will you go?”

“I suppose I will go, but only because, well, what else is there to do?”

“But you don’t see the point?”

“Not really. I doubt there’ll be anything there, anything salvaged from this.”

“When this world started changing, when your garden died, how did you continue to care?”

“What else is there if not hope?”

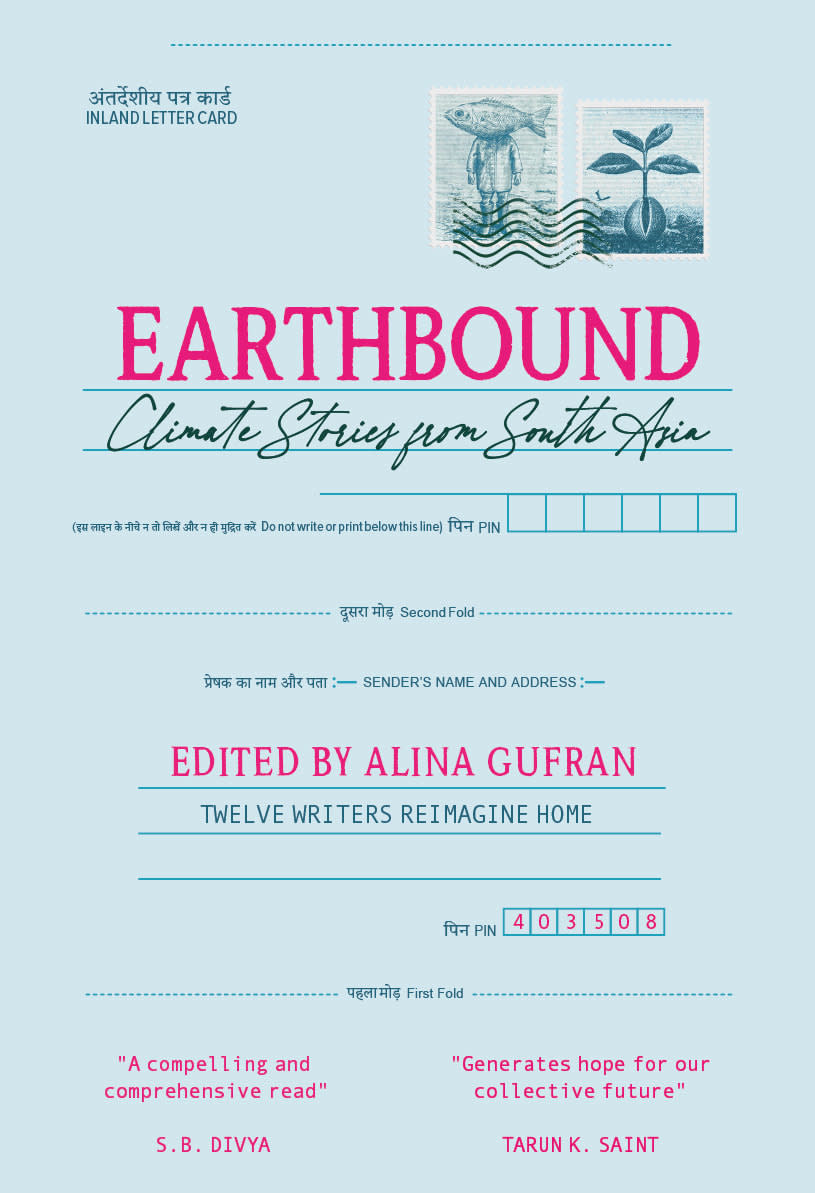

Excerpted with permission from the story ‘Afterlife’ by Rhea Lopez from the anthology ‘Earthbound: Climate Stories from South Asia’ edited by Alina Gufran, published by Storiculture, Price Rs 599.