Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Thinking of the dried-up river near the hill that once used to be full of water and remembering how Hanumant’s grandfather had said that for some reason the river had become angry and gone underground, I suggested that Hanumant and I should go up the hill to look around. I found this story of the angry river very intriguing.

We started the next day. It would take us about one hour to reach the hill. It was not very high and we hoped we could climb it with ease. I asked him, ‘Have you ever gone to the top of the hill?’

‘Many times,’ he said. ‘There was a king’s palace at the top. Now, only a few broken walls are left.’

‘Where has the king gone?’

‘Where would they go? All of them died fighting each other. Baba says that two of his sons fought to become the king and both died.’

This time, we had taken some food with us. I had somehow managed to convince Ma to accept our plan of spending the whole day exploring the hills until evening. Papa had spoken to Bisu Sardar who had told him not to worry. ‘Hanumant knows the surroundings and the people living in the village will also look after Bharat.’

We started climbing the hill. A rough trail, trees and stones helped us in our climb. It was beautiful when we reached the top. We could see the dry riverbed and the village with its dollhouses from this height.

‘Does no one stay here?’ I asked.

‘No. This is known as the hill of the king. It is said that no one should spend the night here. The villagers leave before it gets dark!’

‘What are they afraid of? Are there ghosts here?’

‘Baba says that the king’s treasure is buried here. It is guarded by the snake god. Seeing anyone near this place angers the snakes.’

I didn’t really believe what he said, but I still had to caution him. ‘Look, Hanumant, don’t say this in front of my mother. Otherwise, she’ll stop me from going out with you.’

He understood my concern, nodded and smiled.

Two or three walls were all that was left of the king’s palace, all of which was broken. How old was the palace? One could not tell. At one time, it would have been full of people and activity, but today it was a lonely, deserted ruin in a jungle.

After the climb, both of us were feeling tired and hungry. We shared the sandwiches I had brought and the gur, chivda and chana he had got for the day. I ended up eating most of the food he had brought. He looked at the sandwiches made by my mother and then asked, ‘What’s in them?’

‘Elephants and horses! Eat, try it!’

I’m not afraid of eating an elephant or a horse!’ he replied. ‘Try it. There is chicken in it,’ I urged, but by this time he had already bitten into one, along with a green chilli he had brought with him. He seemed to like the combination very much, because he ate four or five and then said, ‘I will tell you something, but first promise you will not tell anyone.’ ‘Papa says that one should not promise anything without first knowing what it’s about,’ I replied.

‘No, it is nothing bad. If you don’t like it, don’t think about it, but don’t tell anyone.’

‘Well ... I promise. I will not tell anyone!’ I said, curious to know what he wanted to tell me. ‘There is a nag here. I have seen it!’

‘Nag? You mean a snake?’ Then I remembered. ‘You said that the king’s treasure is buried here and a snake king looks after it—the same nag?’

‘Treasure is what they say, but I have seen the nag ... and he is my friend!’ he said and stared, as if to check if I believed him.

‘A snake is your friend? You are a wonderful person—you are like a monkey and you make friends with a snake!’

I actually couldn’t believe him and thought it was all a joke.

No,’ he insisted. ‘What I am saying is true. He sees me and never harms me. When I come here, I bring some milk for him and pour it out for him to drink.’ Saying this, he brought out a small bottle from a cloth tied around his waist, with milk in it. ‘Bharat, I’m going to the other side of the old broken wall. You can come with me—I will then go alone to the other side, as the nag lives there. He does not know you, so you should only see him from far.’

‘He will not bite you?’

Now I was getting scared. Hanumant was clever, but he was also reckless. Who knew what might happen. And the snake made me fearful.

Hanumant was already headed towards the broken wall, and I followed. I was not going to stay behind alone. He stopped near the wall, turned towards me, signalling for me to stay there, and then started advancing further.

The old walls of the broken palace were in front of us, and the surrounding area was scattered with crumbling stones that had plants growing out of them. Hanumant, after crossing the broken walls, placed the milk in a mud cup and put it under a tree. He pursed his lips and made a sound like a whistle. After some time, from between the two stones, a snake slowly slithered out. It was black and quite long.

It came straight towards Hanumant, stopped in front of him, raised itself and spread its hood wide, swaying slightly. I would have run away in fear if my feet had not felt like they were stuck to the ground. I just stood there, transfixed, and I watched. Hanumant started talking to him, shaking his head. What he was saying, I could not hear, but I saw the snake bring his head closer. After some time, Hanumant folded his hands, offered a namaskar and gradually stepped away.

I too wanted to retreat, but my legs started to shake. I managed to go back a few steps, and found a stone to sit on.

Hanumant stood there, watching the snake for a while and then he came towards me.

‘What’s the matter, Bharat? Don’t be afraid-that nag will not harm you. Now let us go down,’ he said, holding my arm as he helped me up.

We walked along for some time quietly. After a while, I asked, ‘How did you become friends with this snake?’

‘One day I had come to the top of this hill and was wandering around. Suddenly, it came out and stood before me with its head held high. I am telling you, truly, I was very scared, but I stood quietly before him. Baba says that a nag never attacks anyone for no reason. Our tribe has been living near this jungle for a long time. We worship the nag. It is said that the nag knows what you are thinking. It looked at me for some time and then went away quietly, and since then, my fear has also gone.’

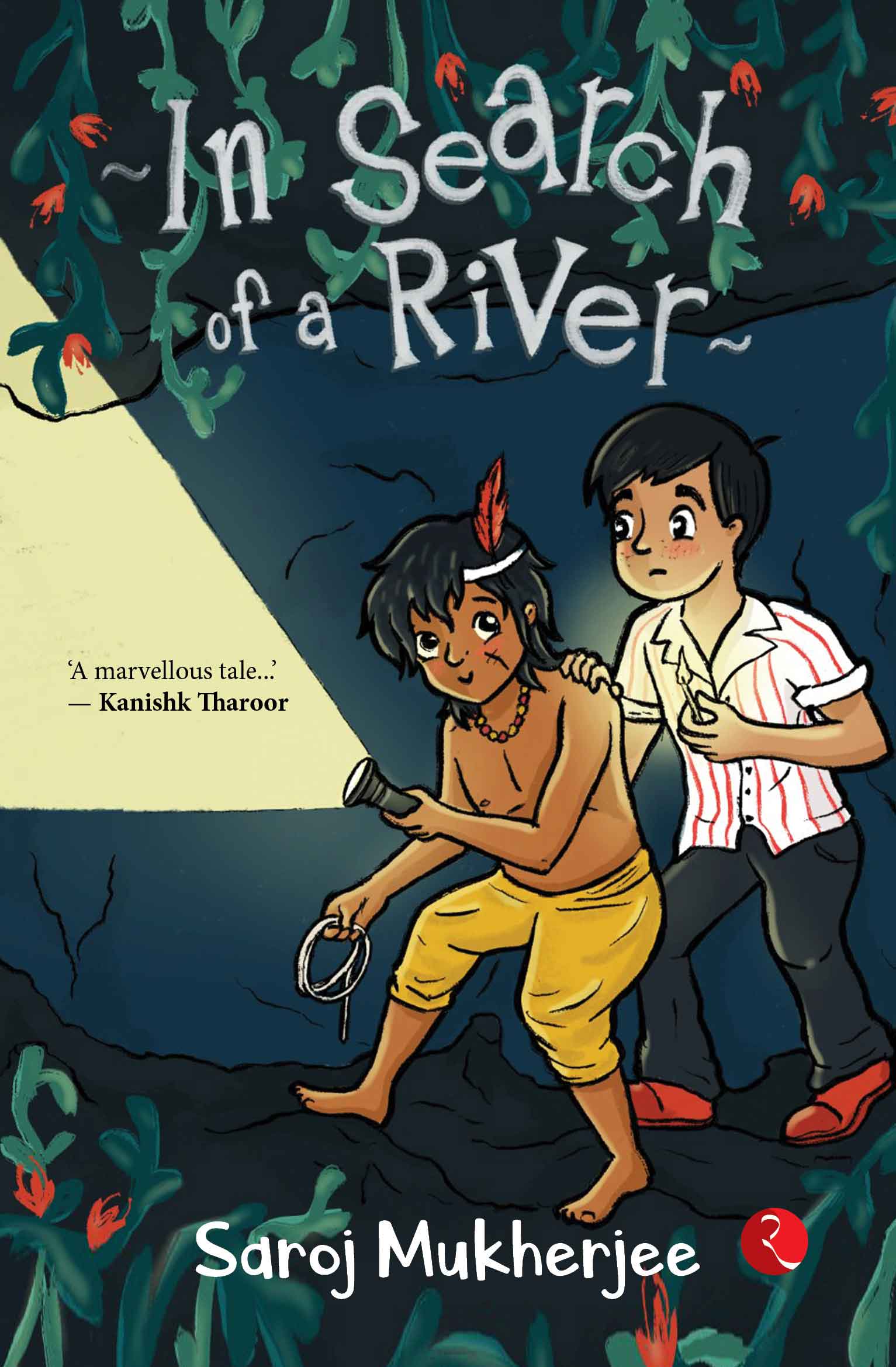

Excerpted with permission from In Search of a River, written by Saroj Mukherjee and translated by Dr. Tilottama Tharoor, published by Rupa Publications, Price Rs 195.