Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

In addition to the gharial, plenty of mugger crocodiles live in the Chambal and we see them basking at the water’s edge, as well as higher up on grassy mudbanks. Though they feed mostly on fish, muggers also prey on mammals that come down to the water to drink. We often forget that crocodiles are the largest predators in India, half again as long as a tiger and considerably heavier. At one point, we come upon a villager walking along the riverbank. He is searching for one of his goats and I ask him if the crocodiles ever feed on his flocks. With a frustrated shrug, he tells me that he has lost several animals to muggers and that they kill cows and young buffaloes as well as goats.

Later on, we pass a broad sandbar, half a metre above the water. Three gharial and a mugger are sunning themselves. The two species appear to coexist peacefully. All of the gharial have their mouths wide open, which gives them an intimidating appearance, though it is not a sign of aggression. About a metre away from the crocodiles, Bachchu points out two species of turtles. The larger of these is the Indian softshell turtle with a leathery carapace three-quarters of a metre long. It is a greenish, grey colour, similar to the wet mud on the riverbank. The pale, wrinkled neck tapers to a point, with two beady eyes and a pair of tubular nostrils. Its large, webbed flippers, with sharp claws, help it swim through the slow-moving waters. Feeding on fish and amphibians mostly, it also scavenges on carrion, including human remains near cremation ghats. Softshell turtles are revered as the vahana of the goddess Yamuna.

The second turtle is about a third the size of the Indian softshell, roughly 35 centimetres long. It has a much harder carapace, with a ridge down the middle and uneven markings that look like slate tiles. But its neck and head are the most remarkable features with bright red, blue, and yellow stripes that converge on a scarlet chapeau. Known as the red-crowned roof turtle, or painted roof turtle, it is one of the rarest reptiles in the Chambal and critically endangered. From its brilliant colouring we can tell this is a male. Females are about twice as large and do not have the bright stripes on their necks. This turtle’s face is different from the softshell’s pointed features; it has a blunt snout and upturned nose. The black pupil and pale iris that study me with suspicion are larger than the softshell’s eye. As our boat moves closer, both turtles scramble into the water and disappear.

The Chambal is home to eight different species of Testudines. In Hindu mythology, Kurma the turtle is the second of Vishnu’s ten avatars, through which he preserves and protects the earth. Kurma is believed to support the world on his shell. He also served as the fulcrum for churning the ocean, when gods and demons sought to extract nectar from the primordial sea. Seeing the turtles basking on the riverbank, it is easy to understand how they might be employed as metaphors of stolid endurance, being species that have survived for many millions of years with their strong, protective shells. At the same time, they live on the edge, both literally and figuratively, emerging from the water to absorb the warmth of the sun but retreating into their fluid world for nourishment and safety.

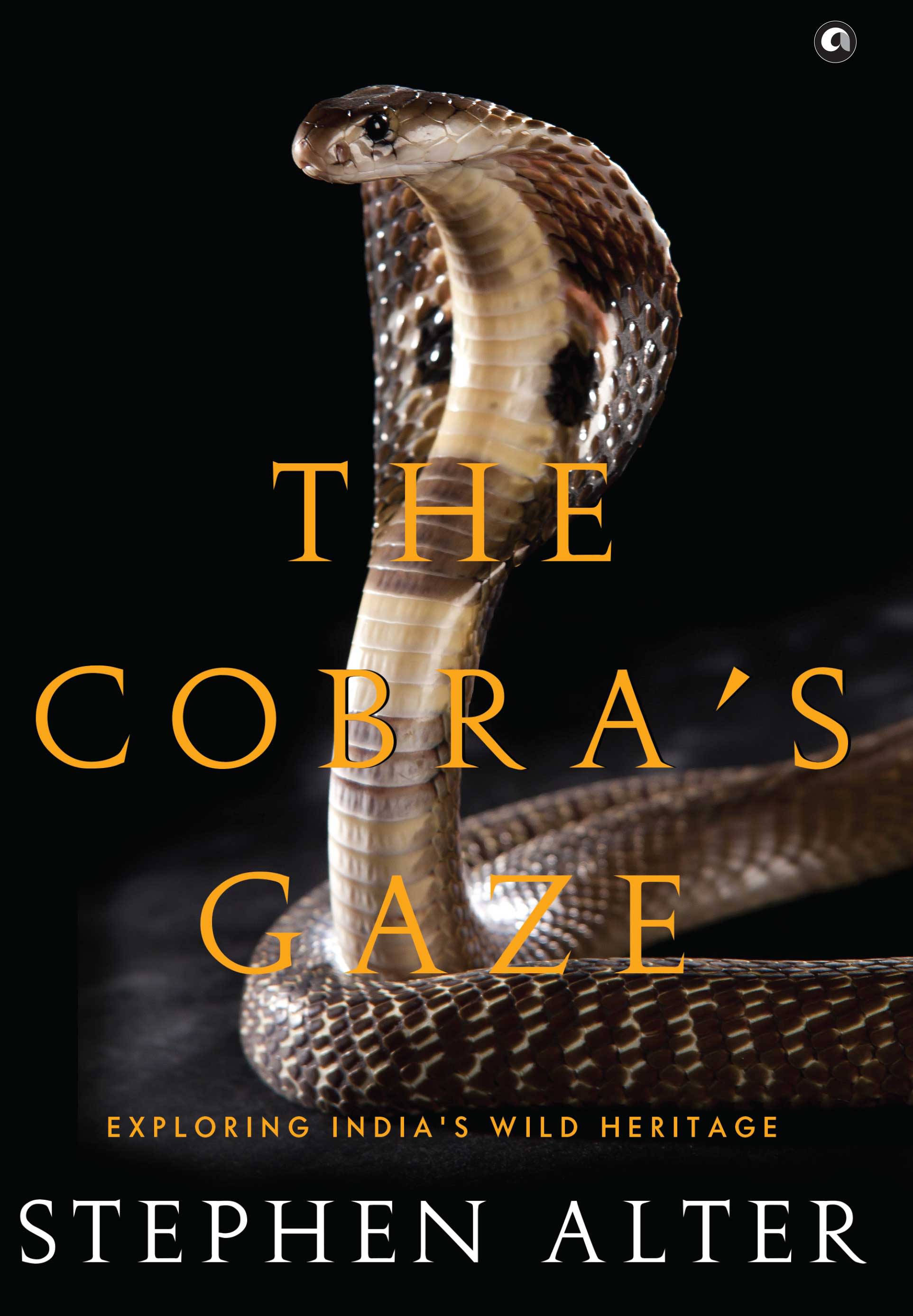

This excerpt from The Cobra’s Gaze: Exploring India’s Wild Heritage by Stephen Alter is reprinted by permission of Aleph Book Company.