Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

The Way of the Chakhesang

It was nearly dusk. The clouds made the forest appear a silvery grey and fireflies glowed intermittently in the drizzle. Frogs were croaking in chorus. But Medolo was listening for a different sound.

He was perched on a rock, with the cold metal of a gun pressed against his arm. It was a rusted old air gun inherited from his father, but it did the job. Indeed, he must have shot more creatures than any other youth in Chizami village. These days, though, that didn’t bring the same respect as it had in the past.

Tweet tweet. A bird! Medolo’s experienced eyes quickly spotted a flash of red and black on the branch of a tree. Quietly, he aimed his gun. But with his finger on the trigger, he paused. There were too many thoughts churning through his head. He kept thinking about a certain squirrel. He tried to slow down his breath and steady his hands. But he had hesitated a bit too long. There was a shout from behind him and the bird took flight.

The person who had cheated him of his shot was Zoweu, a girl from Chizami.

‘Ah!’ said Medolo. ‘An Eco Club member. Just my luck…’ “Yes. Your luck that I stopped you from taking a life. What were you going to do with it anyway? There wasn’t even enough meat on the poor bird,” said Zoweu. “It is July. Hunting is allowed for these two months,’ said Medolo. ‘It is only allowed so that people can stop boars and other animals from raiding their fields. You can’t misuse the rule!” she said.

“Well, what are you going to do? Follow me around all day to shoo away birds?’

Zoweu and Medolo had been friends since they were kids. But lately, like all members of the Eco Club, she too, had taken an oath to not eat wild meat. They hadn’t spoken in quite some time.

“I won’t have to. If you had wanted to kill it, you would have done so already.”

Medolo knew she could see that something had held him back from taking that shot.

Just then, Wekhro and Tekhe, boys who had been hunting with Medolo, came over. “Zoweu!” said Wekhro. “This is Nagaland. We are Chakhesang. Hunting has been in our tribe since generations! How can you forget that? Aren’t you a Naga?’‘

“Eating wild meat does not make me Naga!’ Her eyes flashed. As he watched her walk away, Medolo thought that Zoweu was truly what her name meant — the beautiful one.

It was getting dark. Usually, in the drier seasons, Medolo and his friends used to come in big groups – five, ten, even twenty people at times. The boys hunted birds, squirrels, rodents or deer. The girls collected fruit, frogs and other edibles. They spent many nights in the forest, sleeping around a fire. He remembered how Beto had taught him to make bamboo traps for catching birds. The same Beto didn’t even eat wild meat any more.

“Morning, Adzu keri,” Medolo greeted his elder brother.

Beto looked at the gun near the door. “You went hunting yesterday,” he noted. “Yes,” said Medolo, feeling defensive. “What about you? Were you out planting trees or sweeping floors?” he mocked. Beto’s response was cut short when their younger sister ran inside, shouting, “Beto, look! There’s a Golden Emperor Moth right outside.” She was learning to identify birds and insects using the books Beto had given her.

Beto turned to Medolo. “See, Atshi Kezu. Nagaland is so rich in diversity! We could lose all this if you and the other boys continue this way. You hunt for fun… and to sell the meat for pocket money! You have changed so much since Mother passed away. You don’t want to study, nor focus on football. You used to be such a good player, you could have played professionally.”

The Chizami village church was a gigantic structure at the edge of the village that could seat hundreds of people. Today being Sunday, almost the entire village was on its way for morning mass. As was customary, the women wore traditional woven skirts, and the men donned woven shawls. People looked their best on Sundays. But Medolo was headed somewhere else. Along the main street, he saw a few people still finishing up their morning chores — feeding chicken, stacking firewood, watering plants. He walked on towards the forest just outside the village.

Finally, he reached the spot where he had shot a squirrel a few days ago. He hadn’t realised at the time that it was a mother. When he had found the nest of squealing baby squirrels, he had felt miserable. Since then, he had been coming here to feed the babies. He must have killed hundreds of squirrels till now. But he seemed to be changing. Last evening, before he had been interrupted, he had not been able to shoot…

He observed the squirrels for a long time, loving how they ate from his hand. He climbed down to the village and started towards home. ‘Howe!’ The shout came from Wete Sir, his former schoolteacher.

“Walk with me, Medolo?” They fell in step as they navigated the winding street. “Wete Sir,” said Medolo after a while. “Do you think hunting will destroy our forests?” Wete Sir slowly turned to look at him. “Medolo, our Chakhesang tribe has always lived here. We have systems. Can you see that mountain top over there? That is a rich, dense forest. That’s where our water sources are. Just below that are the jhum fields for shifting cultivation. And below those, are the forests from where we take our firewood. Then we have our village, here, and below us, as the hills flatten out, are the paddy fields.” He pointed to the terraced fields where some women were busy transplanting paddy.

“If you were to disturb this balance…” Medolo knew what he was getting at. Some villagers had started talking about how they no longer had the huge trees they used to have earlier. Too much wood was being cut. This had even affected their water sources. They had to be careful about which trees to cut, which to plant, what fertilisers to use…

Wete Sir continued, “The forest depends on its creatures, Medolo. You know very well that birds disperse seeds, bees pollinate… We have to let them live and do their job.” Medolo said nothing. They had reached the village square, where a few children were cleaning the streets. The students’ union did regular cleanliness drives and tree plantations. Beto was their leader.

Medolo thought about what his teacher had said. Many people in the village were now against hunting. In fact, the village council had made regulations to ban it for most of the year.

“Hey Medolo!” one of the kids called from the village square. “We’re getting together to watch the match this evening. Join us. Man U is sure to win today!” David was one of the children in the Eco Club. Right now, he was intently looking at a clump of bamboo through a pair of binoculars. “What do you see?” called out Medolo, walking up behind him. “Medolo!” David looked at him in surprise. “What are you doing here?” Medolo plonked on the grass beside him and let out a sigh. “In the last few days, I have been questioning a lot of things. I feel my brother may be right.”

There were many children in the field around them, each one with binoculars, a camera or a notepad, silently observing. “So, is this what you do at Eco Club? Look at birds?” “Yes. And we identify them. Look through this,” said David, handing the binoculars to Medolo. “See that bird? That’s a pipit.” “Interesting,” said Medolo, quite fascinated by the binoculars.

“I have learnt so much at the Eco Club, Medolo. We learnt about birds, frogs, snakes… about food chains and the web of life!” Medolo couldn’t help but smile at the children’s enthusiasm.

*

Night had fallen and Medolo was returning home when he came to the thatch-roofed community hut. His grandfather and a couple of other village elders were telling stories to a group of young children huddled around a fire.

Medolo was very fond of this tradition in his village, and he walked in to listen to the familiar Chakhesang folktales. When the people finally began filing out, he went to his grandfather. “Apfu se, I need to ask you something. You were once a great hunter, were you not?”

His grandfather gave a wide smile, making the wrinkles on his face stand out. “So it was, Medolo. But you already knew that. What is it you really want to ask?”

“Apfu se, I need to know if I am doing the right thing. People nowadays say hunting is wrong. Don’t you feel such beliefs are against our tradition?”

His grandfather smiled again. “Medolo, there is much you do not understand… so much you must learn. When I was younger, we were taught everything by the birds and animals. In winter, they slept and it was leisure time for us humans… no agriculture. But by February, an insect would start making a sound. It was asking us to dig water channels to the fields. By the end of March, the kekurhe bird came and told us to tie up our spades. Later, the chirping of the bird kuti told us it was time to sow seeds. By May, the insects jonyi and lilinyi came to indicate that it was time to prepare the wet terrace fields for paddy. In June, a white flower bloomed and it was time to transplant the paddy. When it was time to harvest millet, fuzi would go and pick up a stalk.”

“What does all that have to do with hunting? Everything! We never hunted the way you boys do. Only ten to twelve people in the village hunted. We looked for the biggest animal and hunted that. We didn’t kill everything in sight!” Medolo listened, still confused.

“We didn’t hunt all the time,” his grandfather went on. “Only twice in the year— once before agriculture, as the meat helped us remain strong for work and once when wild fruits fell, as the animals that ate them were healthy. In my youth, these forests were teeming with thousands of creatures. But now, where are they? You must bring them back, Medolo. You hunt because you are too lazy to work in the fields. That kind of hunting was never our tradition! Seeing the forest with all our five senses, listening to what the animals teach us — that is the way of the Chakhesang.”

“I understand, Apfu se,” said Medolo, smiling. “You must listen, my child. The forest will teach you everything!”

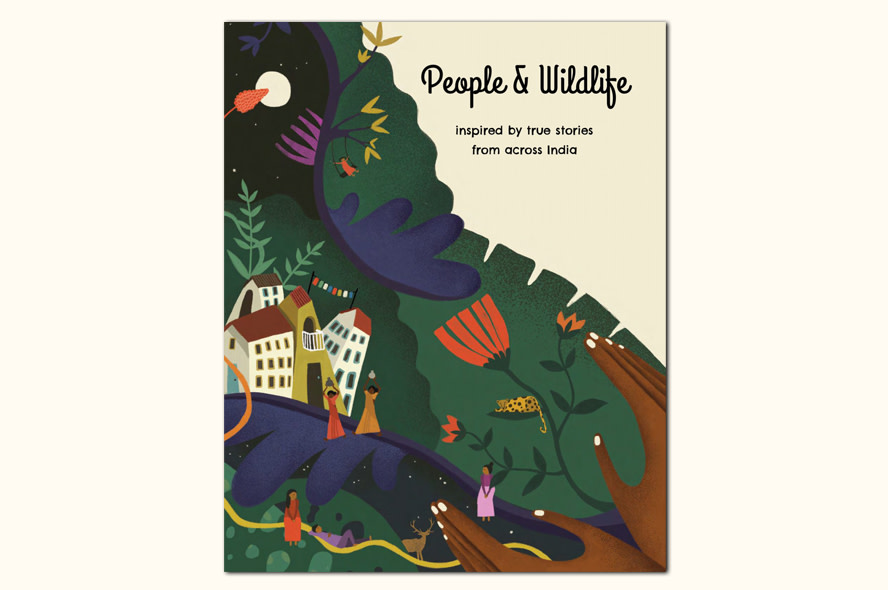

Excerpted with permission from People & Wildlife, published by Kalpavriksh, 2018. Pages: 65. Price: Rs 200.