Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

It is through the power of observation, the gifts of eye and ear, of tongue and nose and finger, that a place first rises up in our mind; afterward it is memory that carries the place, that allows it to grow in depth and complexity. For as long as our records go back, we have held these two things dear, landscape and memory. Each infuses us with a different kind of life.

The one feeds us, figuratively and literally. The other protects us from lies and tyranny.

-- Barry Lopez, About This Life

The horizon flashes intermittent neon in the dark, silhouetting ghostly clouds.

‘Those scattered clouds are called kanthi,’ Chhattar Singh says. ‘If they come together with the promise of rain, they will change to ghataatope. And should the clouds become very dense, they will be called kalaan.’

That night, the kanthi does not build. It does not rain.

As life stirs awake the next morning, Chhattar Singh and I sit with cups of chai and watch the wind ripple through a feathery, fruit-laden khejri tree. He points to the tufts of white cloud trailing in arcs and lines all the way to the horizon. ‘Teetar pankhi,’ he says. The analogy is breathtakingly apt – the wispy clouds are, I notice, akin to the patterns on the primary feathers of a partridge.

I am tempted to ask Chhattar Singh to cycle through the names the desert people have for various types of clouds. But language does not work that way; it is not learned overnight. You need to invest time and patience to listen, to observe, to see and touch and feel, to experience the land with all your senses.

A soft, warm wind picks up. The teetar pankhi clouds flock together into a light cottony blanket overhead. They have a name for that too. Paans.

It is said that the Inuit people of the Arctic region have forty names for snow – which makes sense, since they are surrounded by snow all year and have an intimate acquaintance with all its variations. The people of the Thar get only forty cloudy days in a year, and yet they have as many names for clouds.

The deep western part of the Thar desert lies in Jaisalmer district. It is bounded in the north and west by Pakistan, in the east by Jodhpur, with Barmer to the south and Bikaner to the northeast. The average rainfall is a meagre 100 millimetres in a good year, about a tenth of the national average and a pitiful 2 per cent of the rainfall Kerala and some of the wettest areas in India receive. For the people of the Thar, a sighting of clouds is a memorable event, worth commemorating in a special lexicon, as these moments hold the key to their very existence.

Traditional desert dwellers, many of whom are shepherds, have an intimate knowledge of this vast and differentiated land. They map it not in kilometres but on a much more minute scale. The land slopes gently, barely perceptible to us used to hurtling around in motorized vehicles, rising about a foot over a kilometre.

Yet these barefoot geographers can sense and use this incline to great effect.

We head southwards from the village we are in, under eyloor skies. Kair trees are in full bloom; some have begun to bear fruit. A babbler pokes its beak eye-deep into the coral-coloured kair flower for its nectar, a natural sweetener widely used in the local cuisine. A whistling wind bends the branches of a khejri tree, feathery and laden with long pods of sangri fruit. A husband and wife, camel cart in tow, harvest the fruit with long hooks.

The caper-like kair fruit and the fruit of the khejri tree, sangri, are invaluable additions to a summer menu. In the months before the rains, shepherds also harvest pilu, the tiny fruit of the jaal tree. A mid-summer walk with Chhattar Singh includes frequent halts under jaals to pick and eat pilu, which look like tiny, perfectly round grapes, red when ripe, with a subtle sweetness minus the tartness of the fruit it resembles.

Mushrooms that grow under the lana plant in the monsoons are a delicacy, to be carefully harvested and savoured. Further into the sandy saline desert, orange buds of the phog plant are mixed with curd in winter for baata, a kind of raita. The lana flowers are mixed into winter rotis. Milk – derived from cows, goats, sheep and camels – buttermilk and ghee accompany the fruits.

A desert family, eating the traditional way, will never want for food. Wheat and millet come from khadeens, supplemented with fruit from the commons as per the gifts of the season. Until recently, dwellers in the deep desert had not seen potatoes or cauliflowers, French beans or sugar – and no one suffered from diabetes.

Chhattar Singh waves us off the road and over scree, for which too he has a name – magra. Chinkaras2 dart away from our vehicle, then wheel about and watch us from a distance. In season, it is reportedly common to see mating pairs of godawn, the highly endangered great Indian bustard.

We stop. The ground is now smooth sandstone layered in purple and gold, orange and burgundy. And out of the blue, there is water.

It takes a while to fathom the source of these pools that materialize in the midst of layered rock. Rainwater, percolating through the porous rock further up, has dripped onto stone, whittling it over aeons into a natural cistern. It is several feet deep in some places, and shallow enough in others that we can see through to the rock bed. It is full of freshwater. I kneel, cup my hands, and sip. The water is sweet, strained of impurities by the rock.

The desert people call it a bhey. Unsearchable on Google Maps, these are remembered lifelines, paths to water sources that only the shepherds know, just as they know where the sevan grass ends and the phog plants begin, or how to reach the one area where dune after dune of murat grass can be found. Shepherds pridefully point out that the desert carries in its womb thirty six types of seeds awaiting dharolyuo, the joyous veil of rain that bridges sky and earth and brings forth vegetation. Desert dwellers recognize borders observed by birds, outlines that are thoughtful, meaningful, natural – inspired by geology. With no written documentation to guide them, they rely on memory and muscle, on a visceral interaction with the land, and they are one with it.

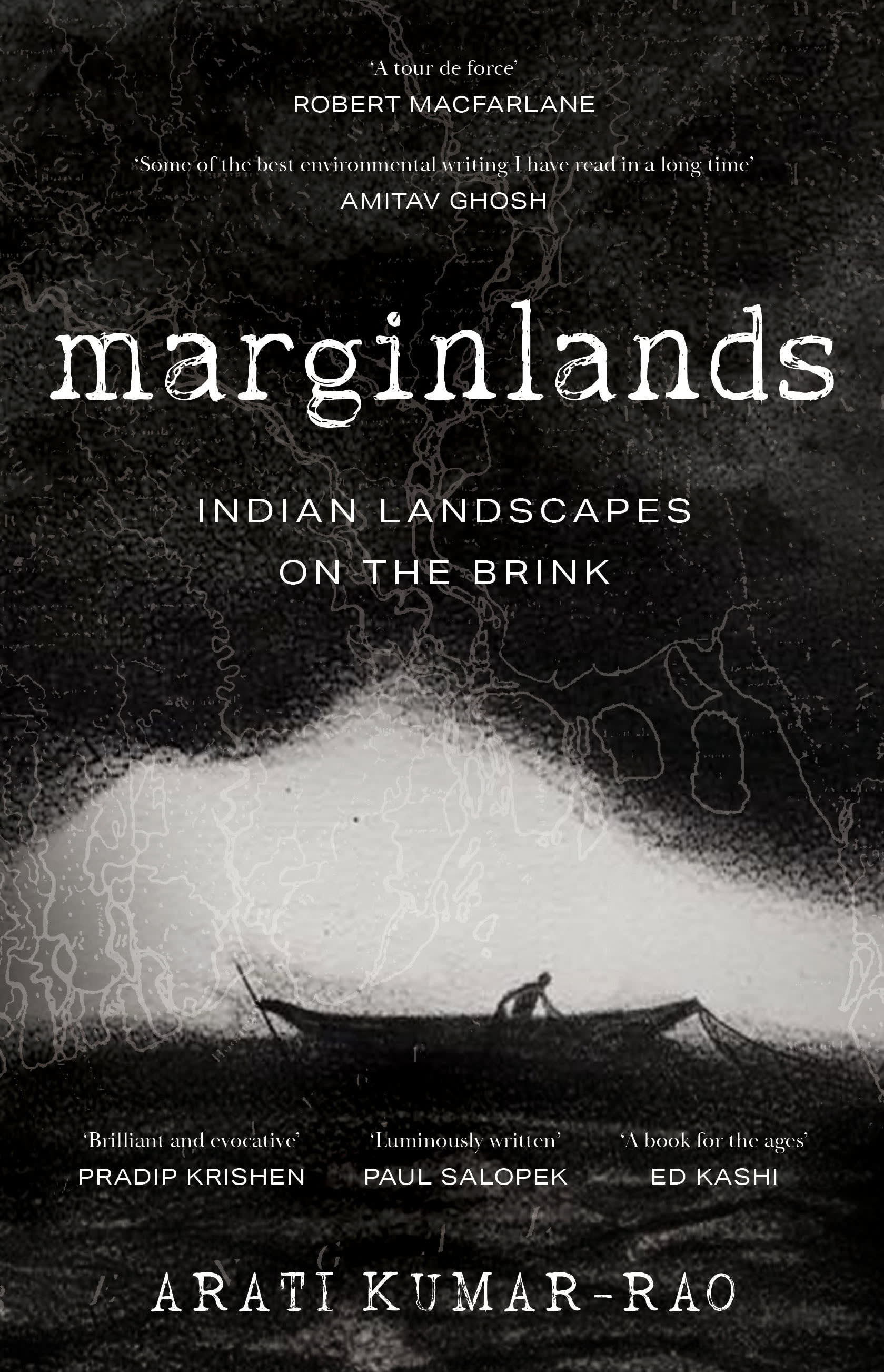

Excerpted with permission from Marginlands by Arati Kumar-Rao. Published by Pan Macmillan India, Hardcover, 256 pages, Price: Rs. 699.