Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

If you are determined, you can find a wilderness close to you, no matter where you live. In 1959, I was living on the outskirts of a greater, further New Delhi. The influx of refugees from the Punjab after partition had led to many new colonies springing up on the outskirts of the capital, and at the time the furthest of these was Rajouri Garden. Needless to say, there were no gardens. The treeless colony was buffeted by hot, dusty winds from Haryana and Rajasthan. The houses were built on one side of Najafgarh Road. On the other side, as yet uncolonised, were extensive fields of wheat and other crops still belonging to the original inhabitants. In an attempt to escape the city life that constantly oppressed me, I would walk across the main road and into the fields, finding old wells, irrigation channels, camels and buffaloes, and sighting birds and small creatures that no longer dwelt in the city life that led to my taking a greater interest in the natural world. Up to that time, I had taken it all for granted.

The notebook I kept at the time lies before me now, and my first entry describes the blue jays or rollers that were much a feature of those remaining open spaces. At rest, the bird is fairly nondescript but when it takes flight it reveals the glorious bright blue wings and the tail, banded with a lighter blue. It sits motionless, but the large dark eyes are constantly watching the ground in every direction. A grasshopper or cricket has only to make a brief appearance, and the blue jay will launch itself straight at its prey. In spring and early summer the ‘roller’ lives up to its other name. It indulges in love flights in which it rises and falls in the air with harsh grating screams—a real rock and roller!

Some way down the Najafgarh Road was a large village pond and beside it a magnificent banyan tree. We have no place for banyan trees today, they need so much space in which to spread their limbs and live comfortably. Cut away its aerial roots and the great tree topples over — usually to make way for a spacious apartment building. That was the first banyan tree I got to know well. It had about a hundred pillars supporting the boughs, and above them there was this great leafy crown like a pillared hall. It has been said that whole armies could shelter in the shade of an old banyan. And probably at one time they did. I saw another sort of army visit the banyan by the village pond when it was in fruit. Parakeets, mynas, rosy pastors, crested bulbuls without crests, barbets and many other birds crowded the tree in order to feast noisily on big, scarlet figs.

Even further down the Najafgarh Road was a large jheel, famous for its fishing. I wonder if any part of the jheel still exists, or if it got filled in and became a part of greater Delhi. One could rest in the shade of a small babul or keekar tree and watch the kingfisher skim over the water, making just a slight splash as it dived and came up with small glistening fish. Our common Indian kingfisher is a beautiful little bird with a brilliant blue back, a white throat and orange underparts. I would spot one perched on an overhanging bush or rock, and wait to see it plunge like an arrow into the water and return to its perch to devour the catch. It came over the water in a flash of gleaming blue, shrilling its loud ‘tit-tit-tit’.

The kingfisher is the subject of a number of legends, and the one I remember best, recounted by Romain Rolland, tells us that it was originally a plain grey bird that acquired its resplendent colours by flying straight towards the sun when Noah let it out of the Ark. Its upper plumage took the colour of the sky above, while the lower was scorched a deep russet by the rays of the setting sun.

Summer and winter, I scorned the dust and the traffic, and walked all over Delhi, in search of quiet spots with some shade, a few birds, flower and fruit. I spent many afternoons lying on the grass near India Gate and eating jamuns. I still remember the sour tang of the jamun which was best eaten with a little salt.

After I settled down in Mussoorie, I would visit Delhi very often, and I came to the heretical conclusion that there is more bird life in the cities than there is in the woods and forests around our hill stations.

For birds to survive, they must learn to live with and off humans; and those birds, like crows, sparrows and mynas, who do this to perfection, continue to thrive as our cities grow; whereas the purely wild birds, those who depend upon the forests for life, are rapidly disappearing, simply because the forests are disappearing.

On a recent visit, I saw more birds in one week in a New Delhi colony than I had seen during a month in the hills. Here, one must be patient and alert if one is to spot just a few of the birds so beautifully described in Salim Ali’s Indian Hill Birds. The babblers and thrushes are still around, but the flycatchers and warblers are seldom seen or heard.

In a city like Delhi, however, if you have just a bit of garden and perhaps a guava tree, you will be visited by bulbuls, tailorbirds, mynas, hoopoes, parrots and tree pies. Or, if you own an old house, you will have to share it with pigeons and, perhaps, swallows or swifts (the sparrows, sadly, have abandoned the city). And if you have neither garden nor rooftop, you will still be visited by the crows.

Where the man goes, the crow follows. He has learnt to perfection the art of living off humans. He will, I am sure, be the first bird on the moon, scavenging among the paper bags and cartons left behind by untidy astronauts.

Crows favour the densest areas of human population, and there must be at least one for every human. Many crows seem to have been humans in their previous lives; they possess all the cunning and sense of self-preservation of man. At the same time, there are many humans who have obviously been crows; we haven’t lost our thieving instincts.

Watch a crow sidling along the garden wall with a shabby, genteel air, cocking a speculative eye at the kitchen door and any attendant humans. He reminds one of a newspaper reporter, hovering in the background until his chance comes — and then pouncing! I have even known a crow to make off with an egg from the breakfast table. No other bird, except perhaps the sparrow, has been so successful in exploiting human beings.

The myna, although he too is quite at home in the city, is more of a gentleman. He prefers fruit on the tree to scraps from the kitchen, and visits the garden as much out of a sense of sociability as in expectation of handouts. He is quite handsome, too, with his bright orange bill and the mask around his eyes. He is equally at home on a railway platform as on the ear of a grazing buffalo, and, being omnivorous, has no trouble in coexisting with man.

Although the blue jay, or roller, is quite capable of making his living in the forest, he also seems to show a preference for the haunts of men, and would rather perch on a telegraph wire than in a tree. Probably he finds the wire a better launching pad for his sudden rocket-flights and aerial acrobatics.

In repose he is rather shabby; but in flight, when his outspread wings reveal his brilliant blues, he takes one’s breath away. As his food consists of beetles and other insect pests, he can be considered man’s friend and ally.

Parrots make little or no distinction between town and country life. They are the freelancers of the bird world — sturdy, independent and noisy. With flashes of blue and green, they swoop across the road, settle for a while in a mango tree, and then, with shrill, delighted cries, move on to some other field or orchard.

They will sample all the fruit they can, without finishing any. They are destructive birds but, because of their bright plumage, graceful flight and charming ways, they are popular favourites and can get away with anything. No one who has enjoyed watching a flock of parrots in swift and carefree flight could want to cage one of these virile birds. Yet so many people do cage them.

After the peacock, perhaps the most popular bird in rural India is the sarus crane — a familiar sight around the jheels and river-banks of northern India and Gujarat. The sarus pairs for life and is seldom seen without his mate. When one bird dies, the other often pines away and seemingly dies of grief. It is this near-human quality of devotion that has earned the bird their popularity with the villagers of the plains. As a result, they are well protected.

In the long run, it is the ‘common man’, and not the scientist or conservationist, who can best give protection to the birds and animals living around him. Religious sentiment has helped preserve the peacock, the sarus. It is a pity that so many other equally beautiful birds do not enjoy the same protection.

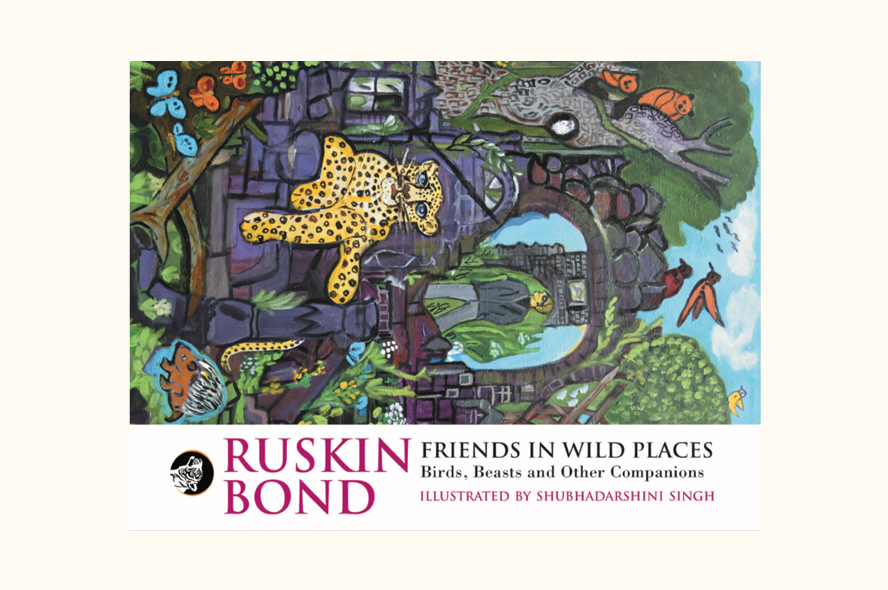

Excerpted with permission from Friends in Wild Places by Ruskin Bond, published by Speaking Tiger. Pages: 159. Price: Rs 599.