Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

It had been six months, four days and three hours since Dad had gone for a staff meeting and never returned. He’d had a heart attack and in four minutes and twenty-five seconds, he’d been declared dead.

Just like that.

One minute laughing, and texting on our family messaging group, and the next, dead.

And, along with it, the world as I knew it ceased to exist. Mom changed. My sister changed. I changed too.

Last year in biology class, Rangarajan Ma’am had taught us about a purple frog that lived in the Western Ghats. As she had pulled up a photo of the frog on the screen, the class had burst into ewwwws. The poor Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis looked like a wet, shapeless balloon carved out of rocks. At that time, I had felt bad for the poor creature which apparently was so shy, it spent most of its life underground, and scientists had failed to notice it until the early 2000s.

Since then, it felt like a bulbous purple frog was sitting on my heart all the time. Cold, hard and clammy. Now it felt like that shapeless, heavy, bloated creature had taken permanent residence in my tiny heart-flat. It pressed down on my heart and my brain, making me feel exhausted. Constantly. Which is why every time I opened my mouth to speak, the words came out wrong. Like the steel that tore the earth apart in quarries and mines. My heart would start hammering, my mouth felt dry, and all the nice words I meant to say would just pop out of my brain. I was cold and hard to everyone.

To Mom. To Meher. To Shabana Fufi, our neighbour in Delhi. To Mamta Mausi, who had worked in our home since the day I was born. To Raghu Uncle, who had ironed our clothes. To Murthy Sir, my favourite teacher. To Khosla Ma’am, the teacher I dreaded most. To Rahul, Chetna and Feroze, my friends in school. To everyone. Soon, it felt easier to say little or nothing. Now I’d never see them again, which meant there was no chance of saying anything mean – the one good thing about this move.

A move that Mom made voluntarily. To get away from it all. New job, new beginnings or some rubbish like that. Shajarpur. What sort of a name was that for a metro city – even if the air was miraculously clean and the weather perfect, untouched by climate change? Where people didn’t need to wear masks. How could the world keep spinning, how was everyone so happy when it felt like my heart was never going to beat again? How could it – with that purple frog squatting on it?

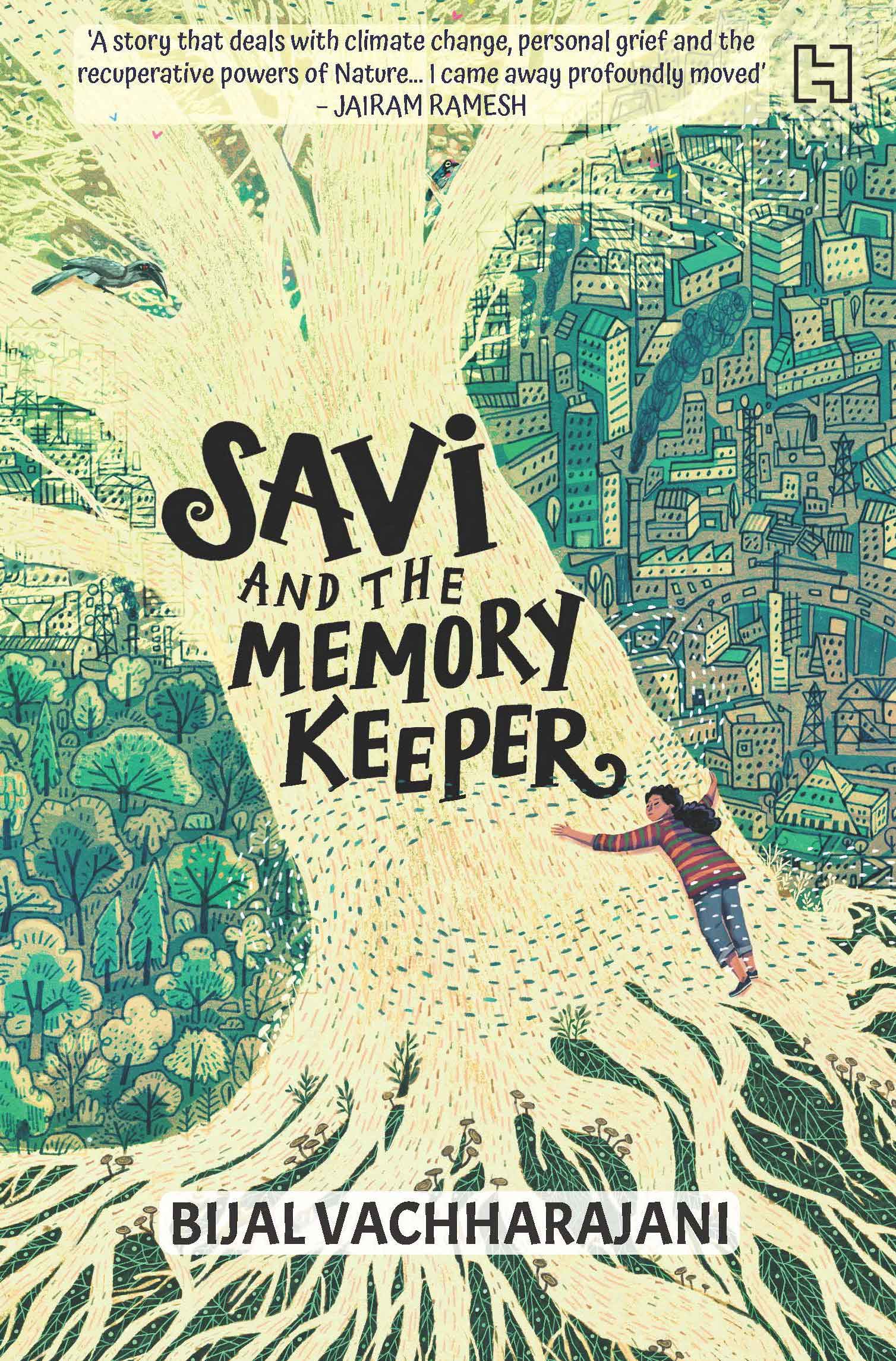

Excerpted with permission from Savi and the Memory Keeper by Bijal Vachharajani, published by Hachette India Children’s Books, Price Rs 350.