Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Moss - The Primitive Plant

Growing in plain sight amongst us are the most primitive of plant forms. Mosses are very different from other plants, because they have no flowers, roots, seeds or fruits. They give us a peek into what plants may have looked like when they were first evolving to grow on land. Without roots, mosses cannot draw water from the soil. Instead, they grow in damp or moist places, where they rely on water from rain, or even a leaky water tank. They absorb this water through tiny leaflike structures. Because mosses retain water almost like a sponge, they keep the soil moist and help other plants grow. Mosses can also dry out for long periods of time and spring back to life with a little bit of moisture. Their simple survival strategy seems to be a winning one, because you will find mosses in a range of different environments, from cold Antarctica, to hot deserts.

Giant Milkweed - The Life of the Party

If you stop to investigate the giant milkweed, you will find that you are not the only visitor. You might see the brightly coloured caterpillar of the plain tiger butterfly chomping away on the leaves of its host plant. The plain tiger caterpillar absorbs toxic substances from the giant milkweed to store in its body. This makes the caterpillar unpleasant to eat, and its bright colours are a warning to its predators: ‘Don’t eat me! I taste bad!’ Other insects are attracted to the giant milkweed for its nectar. The plain tiger flits from one flower to the next, extending its tongue-like proboscis into the flowers for nectar. The carpenter bee dreamily flies between different flowers, and the sunbird dips its long beak and tongue into the flower while hovering alongside. The seeds of the giant milkweed are spread with the help of the wind. The seeds have fluffy white hairs which the wind can easily carry and deposit far from the parent plant. Because of their white ‘beards’, the seeds of the milkweed are called appuppende thaadi (grandfather’s beard) in Malayalam. Many birds like the pale-billed flowerpecker and sunbirds, use these ‘beards’ as their nesting material. Where can you find them? Growing by the side of the road or in an empty plot.

Lichen - Tree Graffiti

Have you noticed squiggly flat patches covering tree trunks, especially in the monsoon? If you look closely at these amoeba-shaped blotches, you’ll see that it’s not just a strange discolouration, but a living marvel. These are lichens, but each one is not a single organism. They are a partnership of algae and multiple species of fungi. The fungi and the algae provide food for each other and produce chemicals that ward off predators. This cooperative system is called symbiosis, and in the case of lichen, the partners are so well integrated that you can’t tell them apart! Together, they become a composite organism and function in new ways which are unique to their partnership. Algae and fungi combine in many ways, with different combinations of species coming together to form lichen under different circumstances. Because of this, 6-8% of all the land on earth is covered by more than 20,000 species of lichen! You can find lichen anywhere, from humid areas at sea level to cold mountainous areas. They grow on different kinds of surfaces, like rocks, tree barks, leaves, man-made buildings, and even on other mosses or lichen. Lichens are long-lived and grow at a slow rate, so a single lichen may live for hundreds of years if undisturbed. If you spot a patch of lichen, use a magnifying lens to observe it up and close. Keep an eye on some neighbourly lichen and see if it grows over time!

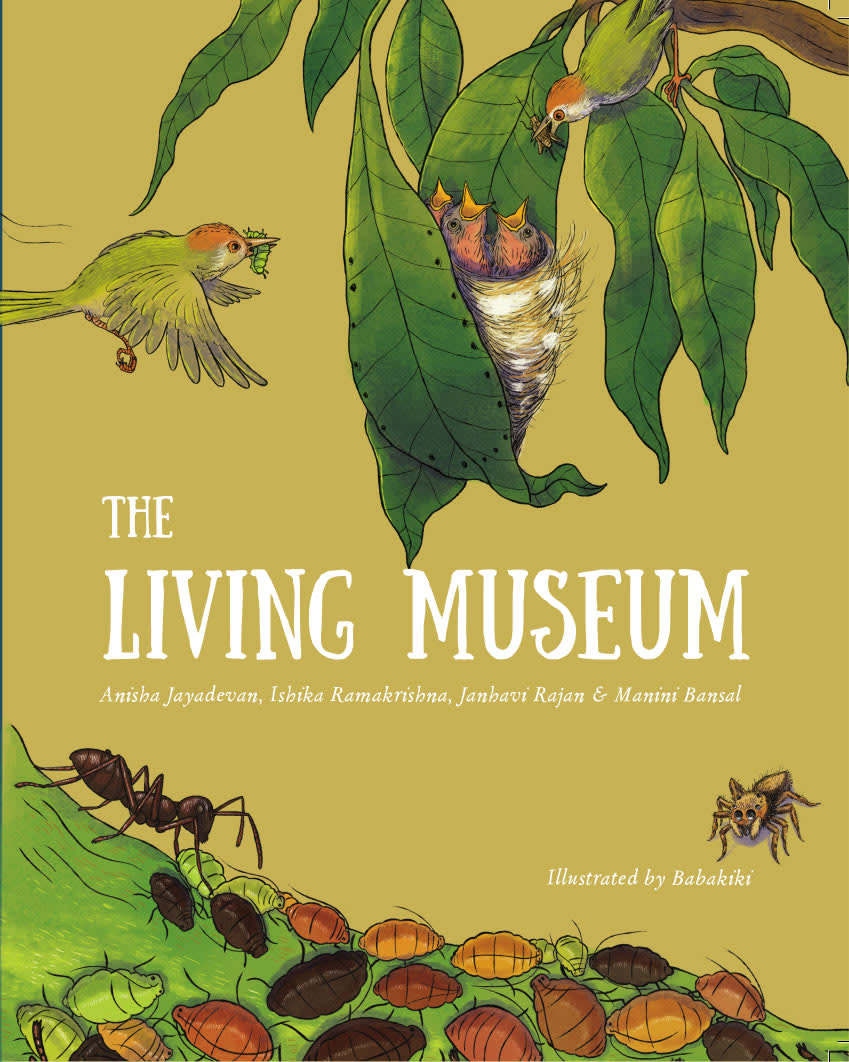

Excerpted with permission from The Living Museum by Anisha Jayadevan, Ishika Ramakrishna, Janhavi Rajan & Manini Bansal, with illustrations by Babakiki. Published by Foundation for Ecological Research Advocacy and Learning.