Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Cane fronds brush past my face as I climb up a narrow path. Overhead, the sharp “keeee-keee-kee” of a crested serpent eagle pierces the air. I look up, but the canopy hides my view, allowing only glimpses of blue to filter in. Further up the slope, the familiar sound of a temple bell surprises me. Is there a temple in this area? I listen in wonder as the steady vibration builds to a crescendo. It is, in fact, a tiny, almost invisible denizen of the forest. The bell cicada (Dundubia hastata), often called the bell of the forest, has just announced its presence.

We are in the first Community Conserved Area (CCA) in the Lower Dibang District of Arunachal Pradesh. In June 2022, following months of deliberations, the residents of Elopa and Etugu villages belonging to the Idu Mishmi community decided to protect 65 sq km of their ancestral customary land. This led to the establishment of the Elopa-Etugu Community Eco-Cultural Preserve (EECEP), another crucial step for the Idu Mishmis who have sustainably managed their community forests across Dibang Valley for generations.

I am with a group of motivated Idu Mishmi who were involved in the establishment of the EECEP and refer to themselves as the Dibang Team.

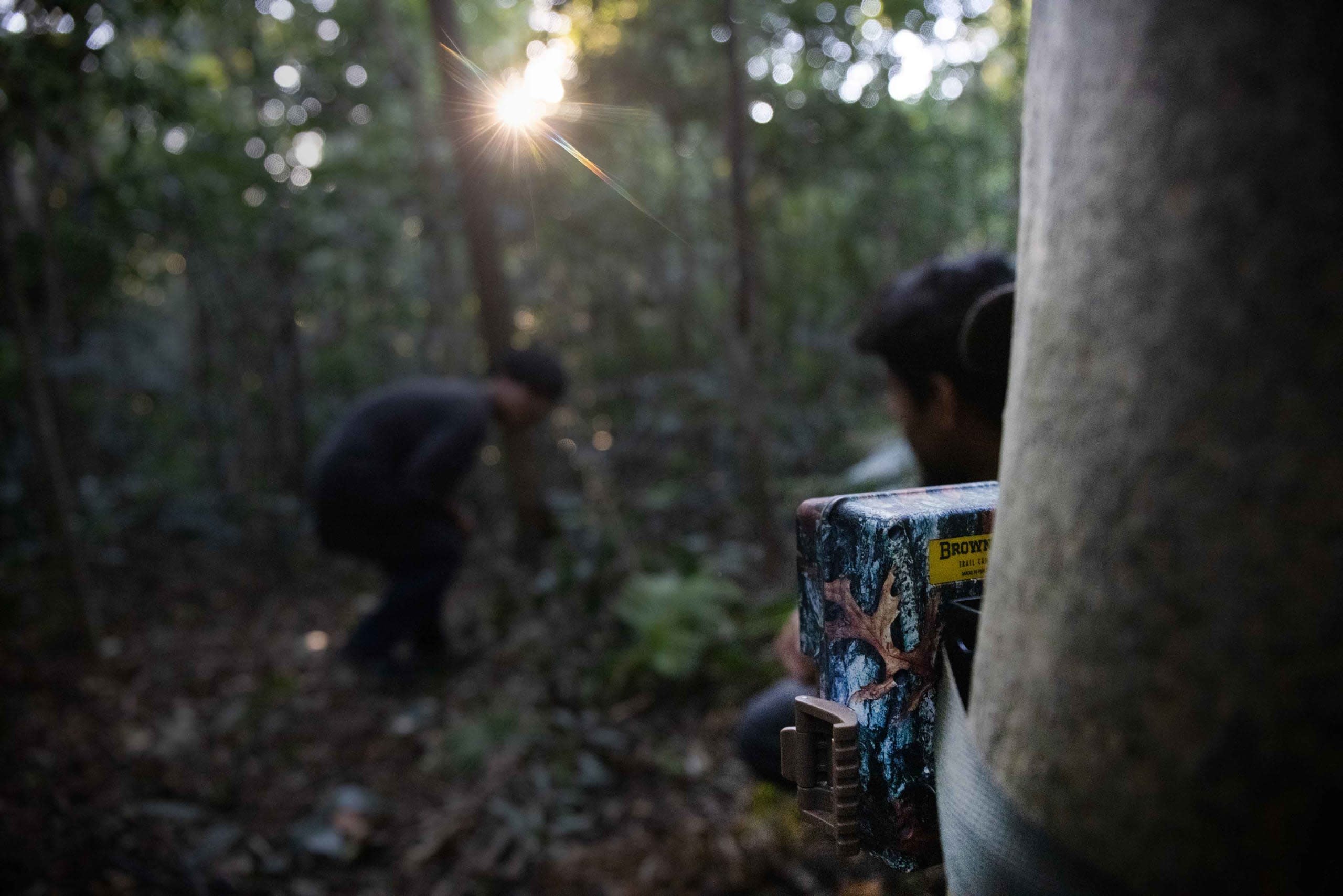

Cover photo: After fixing a camera on a suitable tree, members of the Dibang Team test the field of vision and motion sensors of the device. Here a community ranger crouches to mimic an animal on four legs.

As the symphony fades, EECEP clan member and grassroots conservationist Iho Mitapo quizzes the young Idu rangers posted here — Ram, Johnny, John, and Lahi — on the Idu names for plants around us. Lakashu is for thin cane while lãkabõ-toh refers to thick cane, my mind registers. The lively conversation is a lyrical mix of Arunachali Hindi, Idu, and English. The rangers are eager to learn more about their region’s biodiversity. And no wonder — this forest hums with life in the middle of the afternoon.

I’m on a reconnaissance visit with wildlife photographer Shivang Mehta and conservation anthropologist Sahil Nijhawan, along with Iho, Chamali, and Eja of the Dibang Team. The team of individuals spanning diverse professional backgrounds is bound together by the common goal to safeguard nature and Idu Mishmi culture. Over the next two days, we will trek and camp across the CCA to set up camera traps in an effort to document the wildlife in the forests that the Idu Mishmi have historically managed.

We stop at a strategic point on a ridge to fix our first camera trap. The exercise also serves as a training session. “Place the camera according to the tree and the trail," Iho instructs the rangers. "Remember to tilt the camera down to face the trail so that markings on the hide can be captured,” he continues. This is a fine example of locally-led conservation that integrates modern technology with knowledge exchange between researchers and the community.

Our camp for the night is the first Elopa village. Over time the villages of Elopa and Etugu moved down to the riverbanks, near their fields. Later, in the 1980s, the fields by the riverbanks were washed away when the river changed course and the clans resettled in other areas across the valley. As we walk, I learn that the name Elopa is derived from Elombõ, the Idu word for possibly the East Indian almond (Terminalia myriocarpa), while Pa signifies an area with an abundance of a tree species. Time and again, snippets like this serve to underline the intimate connection that the Idu have with the land.

In spite of the relocations, clan members continued to gather on their customary land, often donating time to repair structures at the original village site. In an earlier conversation, clan elder Jibi Pulu, who was instrumental in mobilising the four clans to establish the CCA had shared that “The acronym EECEP, when pronounced as a word (ee-see-ee-pee) translates to “a place we left a long time back” in the Idu language. It holds deep meaning for Elopa-Etugu’s clan members.”

Loud whooping cackles pull me back to the present. It's the calling card of the white-crested laughing thrush. We have crossed the ridge, and the forest is now denser. The temperature drops swiftly. We set up a few more camera traps along the way and reach a clearing shortly before sunset. I notice stick insects all around me. Mating pairs balance on blades of grass, sans camouflage. Above, a pair of orange-bellied leafbirds perch on the bare branches of a tall tree, lit by the auburn of the setting sun. Sitting around the fire that night, we discuss the plan for the next day. Anecdotes pepper the conversation, highlighting the commitment of the team. One that particularly touched me was about how the team spent two days without water in the mountain behind us, while setting up camera traps for the first time.

It was this camera trapping that helped establish, by means of visible proof, the biodiversity (hog deer, Himalayan serow, four types of civet, clouded leopards, two types of bears) that the community forest supported, despite unregulated hunting and extraction of resources. Since the institution of the CCA, there is a ban on blast fishing, commercial hunting, and the sale of timber. It also means that the land will remain with the community and no single individual may sell or occupy it. Members of the Pulu, Mitapo, Linggi and Menda clans can conduct traditional fishing and small-scale collection of forest produce, but not outsiders.

Back around the fire, it's easy to see from the conversations how nature is central to the traditional Idu Mishmi way of life. A part of the Eastern Himalayan Global Biodiversity Hotspot, Dibang Valley is home to a staggering range of flora and fauna and is known to be one of the richest bio-geographical provinces of the Himalayan zone. But a lot is changing over time for both Idu and the valley they call home. The valley has been selected for a series of hydroelectric projects, of which the Etalin Hydro-Electric Project and the Dibang Multipurpose Project have been in the news recently. The CCA is in the lower Dibang Valley, close to the Multipurpose Project site at Mulli. Work has begun on what will be India's largest dam at a staggering height of 278 metres. The proposal involves disrupting the habitats of the Asian elephant, hoolock gibbon, clouded leopard, and tiger. The mountains upstream of the projects contain glaciers and glacial lakes that feed the rivers. These glaciers are melting and thinning on account of climate change and could cause sudden floods.

This ecologically and geologically fragile landscape is changing, and developmental projects in the pipeline could hasten the process. The landscape of the ECEEP CCA is unique because grasslands have formed as a result of the river changing course. On our way in, we briefly spotted a jackal in the tall grass. Sahil tells me that that camera traps have also captured the presence of critically endangered Chinese pangolins in this area.

Climbing up into the mountains, the vegetation changes to wet tropical forests mixed with wet subtropical strands. According to the team, in addition to conservation efforts, the CCA provides a framework to engage with indigenous communities across the valley on issues pertaining to the privatisation of common lands, and collective decision-making. A committee of representatives from all four Idu Mishmi clans manages the CCA, with a mandate to protect wildlife, restore degraded habitats, and create income sources for villagers through community-led research and sustainable tourism. The Dibang Team, consisting of Idus from across the valley, and the EECEP are supported by the Nature Conservation Foundation.

When I retire to my tent that night, my torch illuminates stick insects perched on the outer side of my temporary home. The next morning, we walk to the sheer cliffs some distance from the campsite, where one could spot Himalayan serow if luck favoured them. From our vantage point, the mountain on the other side seemed to be collapsing into itself. Historically, Dibang Valley is a seismically active zone, and landslides in the area are frequent. A massive earthquake in the 1950s is said to have razed the forests around us.

As we stand on a windy overhang, the river sparkles far below. I see movement in a landslide on the opposite mountainside. Something dark in the sea of broken mountain. Excitedly, I reach for my binox and spot a Himalayan serow with her calf crossing the landslide carefully, camouflaging into the dry grass with ease.

Back at the base, we gear for a day of camera trapping on our way back. On the trails, I now notice animal tracks everywhere, signaling their movement almost like tyre tracks on a road. At the base of a tree overlooking the valley, we notice a deep indent in the leaves, possibly sambar deer. “Bedroom banake soya hain”, Sahil remarks.

Sahil explains that a hybrid model is used to evaluate and monitor wildlife (ungulates, primates, felines) in EECEP. While some of the points on our route are marked on trails that predators like big cats and small carnivores regularly use - the bulk of the camera points are randomised locations that help to estimate populations of ungulates and primates. This means navigating to the point on the map, often making our way past bamboo and cane on slippery and steep terrain. Holding onto lianas and navigating through thick forest, we make our way setting camera traps at points across narrow ridges, through thorny vegetation, and down steep slopes to finally reach the dry riverbed of the seasonal Ishi river. Walking along the riverbed, we notice animal tracks — bear, martin, sambar, small cats — that the team had not observed here earlier. Preliminary data from the cameras retrieved by the team in May 2023 establish the presence of at least six different clouded leopards in the CCA, a healthy large carnivore population suggests a healthy prey population. The number of smaller carnivores like crab eating mongoose and civets appear to have increased. Interestingly, the team also found that the population of hog deer, a grassland species, numbering a few individuals at the start of their monitoring has risen significantly.

We finally reach the rendezvous point as the sun retires for the night, painting the sky in shades of orange and purple. Waiting for the other groups, I study the landscape. Each time the river floods, it brings stones and sand with it, reshaping this part of the CCA. On our drive back, a full moon hangs low, framed by tall elephant grass in the foreground and the mountains behind. We stop to enjoy the moment. I look around, everyone looks exhausted, but their faces are flushed with joy. Their eyes sparkle. Love for their landscape is evident.