Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Sea cucumbers are cylindrical, soft, sessile (sedentary) marine organisms that live on the seafloor. They play an important ecological role in nutrient cycling. The burgeoning market demand for sea cucumbers from Southeast Asian countries, mainly China, has brought attention to the illegal trade. Much of this demand stems from sea cucumbers being considered “aphrodisiacs of the ocean” with believed medicinal properties. In India, the illegal sea cucumber trade impacts marine ecosystems and the livelihoods of artisanal communities who have historically harvested them.

Illegal wildlife trade is a complex phenomenon. Often, ahistorical and apolitical explanations of sea cucumber trafficking divert attention from the source of the problem. The once thriving sea cucumber trade was turned illegal with a blanket ban imposed by the Indian government in 2001. This “one-size-fits-all” approach in marine conservation produces flawed outcomes and exposes the fault lines in biodiversity conservation policy and practice.

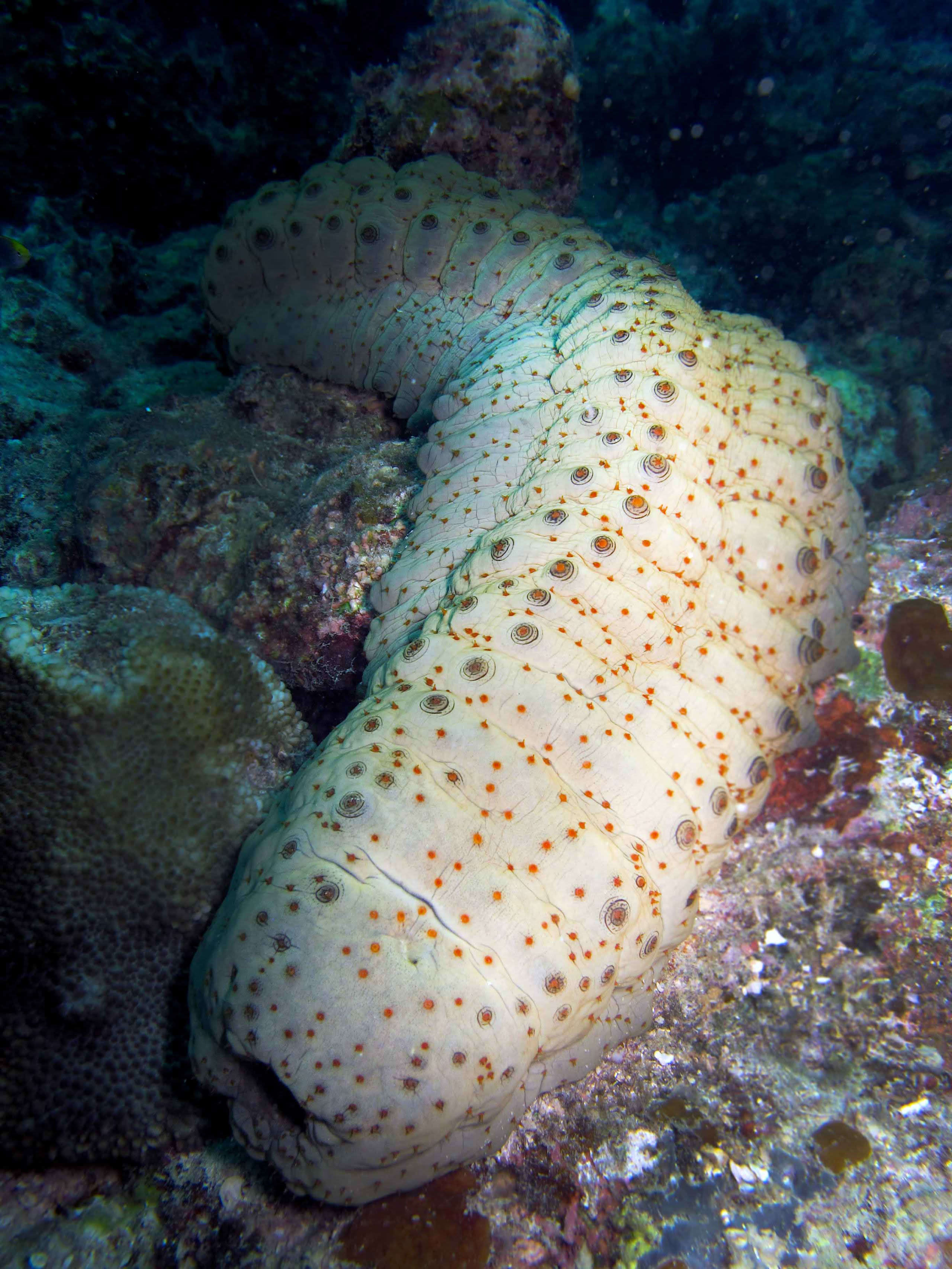

Cover photo: Herrmann’s sea cucumber (Stichopus herrmanni) is found throughout the Indo-Pacific and the Red Sea regions at depths up to 25 metres. It is one of the species illegally harvested in India. Photo: Vardhan Patankar

History of sea cucumber fishing

Sea cucumbers are found in certain pockets along the Indian coastline. Palk Bay and the Gulf of Mannar host species such as vella attai (Holothuria. scabra) and paal attai (Actinopyga echinites) that are sought after in the global market. In 1917, the English zoologist James Hornell noted that the sea cucumber trade between India, Sri Lanka, and China is at least 1,000 years old. Breath-hold freediving to collect sea cucumbers has been a traditional occupation for several thousand artisanal fishers in the region. Freediving to handpick sea cucumbers is a gentle, skilful, and labour-intensive activity which controls effort and supports the poorest fishers in the region. The divers use minimal equipment — a locally made glass mask, an aluminium plate that acts as a flipper, and a bag around the waist to collect sea cucumbers. In the past, the Department of Fisheries in Tamil Nadu was actively involved in promoting sea cucumber harvesting by training fishers, enabling access to rich fishing grounds, and providing the means to process the catch by boiling and drying them for export. In 2001, citing conservation concerns, the Indian government imposed a blanket ban on sea cucumber harvesting, which affected traditional livelihoods and criminalised the artisanal fishing practice.

Intensification of mechanised bottom trawling

In the early 1950s, mechanised bottom trawlers were introduced in India as part of efforts to modernise fisheries. Bottom trawler technology, originally developed for temperate water countries, is unsuitable for biodiversity-rich tropical seas. Shrimp is the primary target for trawlers that use large, heavy nets to drag along the seabed. The gradual expansion of bottom trawling has resulted in ecological damage to near-shore waters and has also caused violent conflict with the traditional artisanal sector.

Initially, sea cucumbers were an incidental catch in bottom trawling operations. However, seeing how lucrative sea cucumbers were in the global market, bottom trawlers began to indiscriminately harvest sea cucumbers, including undersized animals. Specialised gear called attai madi (sea cucumber nets), though officially banned in the region, began to be used to harvest sea cucumbers, triggering sustainability concerns.

Unlike selective handpicking of sea cucumbers by artisanal fisheries, bottom trawling doesn’t discriminate between adults, juveniles, or even eggs. Bottom trawling for shrimp is considered one of the most destructive fishing practices, as it catches over 400 non-target species as bycatch.

In 1982, the Indian government banned the export of sea cucumbers less than two inches long, based on inputs officially provided by the Marine Products Export Development Authority (MPEDA). After this initial ban, data collection on harvested sea cucumbers dwindled. The conservation benefits of the blanket ban imposed in 2001 are also up for questioning as there are no reliable density estimates pre and post-ban.

Repercussions of the blanket ban on sea cucumbers

After the blanket ban in 2001, the prices of sea cucumbers doubled, providing further motivation to engage in sea cucumber trafficking. Once a thriving trade among artisanal fishers, the ban led to the trade being taken over by more organised and powerful actors, such as trader networks who traffic sea cucumbers to Sri Lanka and from there to other transhipment points. Extreme poverty and low incomes during the fishing season have pushed artisanal fishers to harvest sea cucumbers despite the ban. Unlike in the past, artisanal fishers are forced to sell their harvest at lower prices to traders, while state authorities label them criminals. Artisanal fishers in the region have held several protests and taken legal action demanding the government lift the ban on sea cucumber harvesting but in vain. They also demand that the state control and regulate trawling, which impacts sea cucumber populations more than their traditional livelihoods do.

When people engaged in sea cucumber trafficking are caught, state authorities put on a spectacle of elaborate photos for the media. Through this publicity, state actors like the forest department try to build legitimacy and public trust and show their serious engagement in enforcing conservation measures. However, the root of the problem — mechanised bottom trawling and its destructive ecological impact — continues to escape official attention and analytical scrutiny.

Given the political-economic priorities to use commercial fisheries to increase seafood production and earn foreign exchange, the state turns a blind eye to bottom trawling, despite its ecological impact. On the other hand, the steady increase in demand for sea cucumbers in the global market has also led the state to resort to piecemeal solutions at the expense of further marginalising and criminalising artisanal fishing communities. As a result, neither sea cucumbers nor the ecosystem in which they thrive are protected despite a two-decade-long blanket ban in the region.