Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

"I brought it to show you and Shashu," Aai said.

It was monsoon. The first pandemic year. I was brushing my teeth. Aai gingerly walked into the room in her nightgown, a leaf in her hand. On the leaf was crawling a bright red button. She landed the creature on my chair. It spent an hour crawling up and down the armrest. Its redness was so vivid, it washed away the greyness I had felt for weeks. I learned later, its name — a red velvet mite.

I was 29 at that time, and Shashu, my nephew was three. For her, we were both children. Or just two people who could savour the gladness of nature with her.

When my nephew was a newborn baby in the hospital, my mother would take him outside to sit in the sun. I looked at their sun-soaked faces and melted. Freshly minted baby in the arms of freshly minted grandmother. And upon them, the sun that has overseen so many generations of our species.

My mother’s childhood was spent in various railway towns. Her father shovelled coal into railway engines. Later, he became a train driver. She fondly spoke of the jamun and guava trees she grew up with. The pet dog she once had and how her death had affected her brothers.

We lived in the city. We never had a pet. Except rats. Plump ones. Aai, juggling a full-time job with family duties, had no time to hunt and kill mice. Even after taking early retirement and moving to a village with my father, she stayed lenient. When one of them jumped on me, she'd playfully mimic: ‘Arey it is happy you are home! Raju Tai aali Raju Tai aali’ - ‘Raju sister is here,’ as if the rat was my sibling.

When I was in middle school, we would take morning walks on the quiet ring road behind our house. She helped me pluck madhumalti and orange trumpet flowers for my teachers. My mother, despite studying nuclear chemistry, loved botany more. I remember her long, slender fingers showing me the milky sap of tradescantia, the houseplant with long, deep purple leaves. Learning plant names from her was like inheriting gold jewellery.

Aai worked for 33 years in Life Insurance Corporation (LIC). She taught me about insurance when I was young. She handled death claims and spoke passionately about securing the future of your loved ones. Zindagi ke saath bhi, Zindagi ke baad bhi, — With you in life, with you after life, she recited the LIC slogan with pride.

She issued many insurance policies for all of us. She supported not only my education, but when conventional education and subsequent jobs rendered me in a deep existential crisis; she supported my rehabilitation.

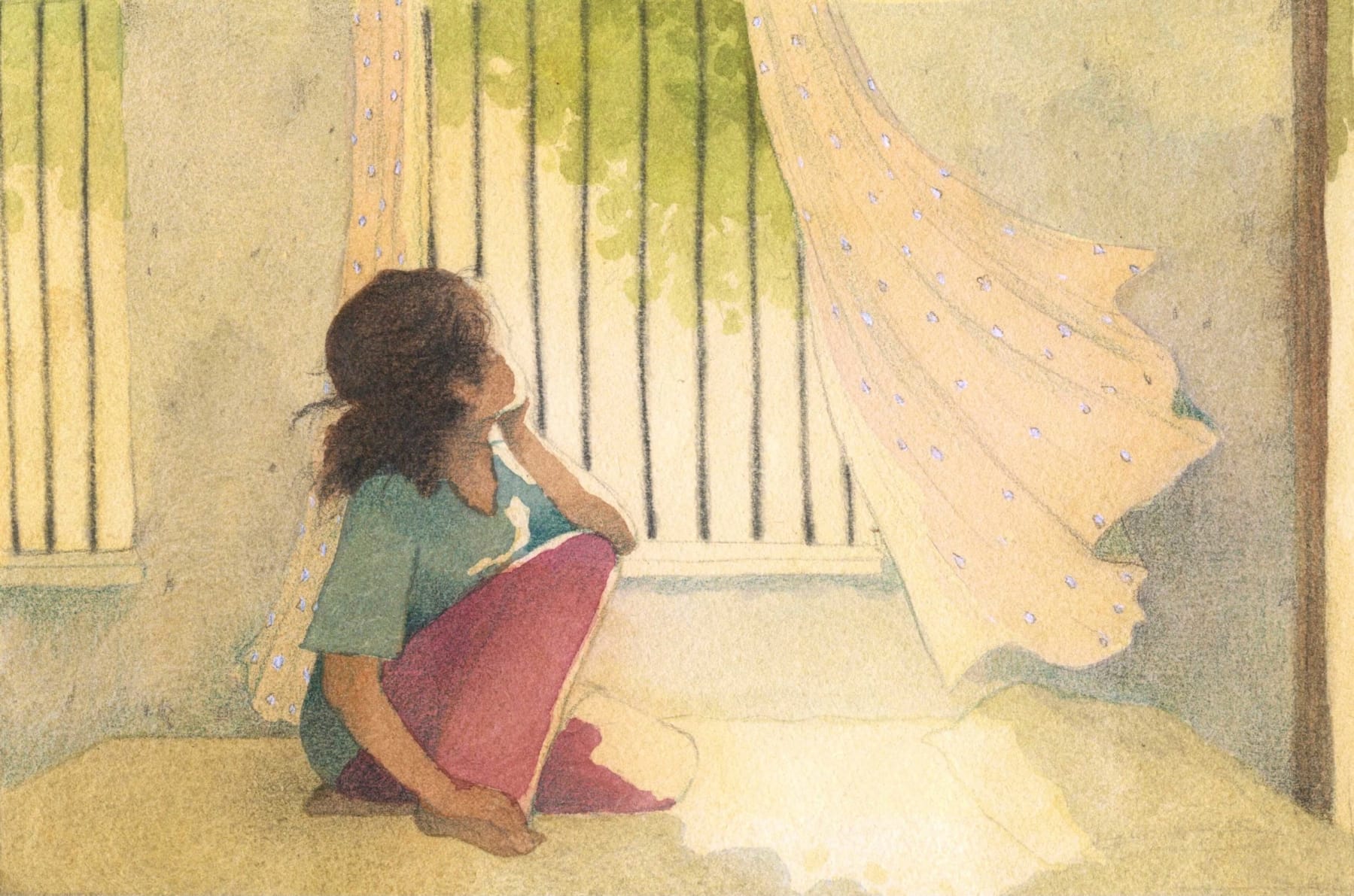

I had returned to our village home when no job, no city, no living situation seemed hospitable. She took me to the sunroom. The room had huge windows. “‘You will get loads of Vitamin D here,”’ she would say. I found it too harsh.

Slowly, the farm outside the room felt beautiful to stare at. We saw bulbuls feeding their young ones. Golden orioles chasing one another. Tiny oranges growing on the orange tree.

In a birthday card, she drew me as a caterpillar growing into a butterfly. She could have compared me to other youth, more settled in their straightforward careers and marriages. But with the guidance of nature, she found a richer metaphor to understand my journey.

She was no longer just a mother. She became a patron who waited until I found my calling — a creative life in writing, poetry, teaching. Eventually, this butterfly took flight and went to other cities.

One day, I received the news that my mother is no more. It was, thankfully, a dream. She came to meet me one last time. In the dream, she had silver hair. She told me we will continue to meet in Kaavya Kala Vaatika — the garden of poetry and art. I took this dream to my therapist, and of course it was not about her dying. It was about me growing up. It was about meeting her in a new common ground. Not belonging to a family with the same surname, but equals sharing the joy of nature, poetry, art.

I had never seen myself as a nature lover. Nor is my mother a quintessential nature nerd. But I discovered how much it is a part of our everyday life, especially when I am with her. She calls a baby bird chuchubala and a tiny yellow flower a chintunana. She paints love notes on peepal leaves for the teachers she works with now. She paints swirling galaxies and makes turmeric pickle. When I am away, she video calls me to show me the full moon.

My mother is not perfect. She upholds a strict binary of good and bad. She holds everyone, especially herself, to exhaustingly high expectations. She consumes way too much WhatsApp than necessary. But she can keep her buzzing phone away and sleep. She doesn’t check WhatsApp while waiting for me outside the trial room.

She decided to let her hair turn grey, while her friends, relatives, even my father had been colouring their hair black. Her curls have begun to shine with the silver in them. I don’t know if it is this or the fact that she is caregiving for two of my grandmothers, I feel she has aged rapidly.

That makes me feel scared of her death. But hiding age is hiding from death. And she doesn’t hide. I have decided to stop hiding too. Nothing can prepare me for the grief her death will bring. But I learn that her favourite movie is Anand, a celebration of death. For her, death is natural. It is the ultimate transformation.

”Thembe thembe taley sache,” “drop by drop the lake is full,” she tells me about saving money. That’s how she paid for our car and our house, securing our financial base. In the same way, she loved nature and taught me to love it, one drop at a time. One flower at a time. All at once, it would have been overwhelming for me.

Thinking about her mortality makes my chest tighten, my throat close up. Yet, consciously inheriting her awe for nature will certainly embolden me to face my life. As a creative person who constantly navigates anxiety and dissociation, nature offers me a vitality that enriches every part of my being. In its raw presence, I discover a way to accept my life exactly as it unfolds.

As I write this, she sleeps on a bedsheet with big blue flowers and is covered by a razaai with small purple flowers. Her gown is full of pink lotuses. Her mouth is open.

I know that after she is gone, the green of the neem leaves will haunt me with its beauty. The pungent garlic will feel stronger in my nose. The golden orioles will look yellower. Because she will want me to see. She will want me to smell. Losing her will kill me. Losing her will make me alive in a whole new way. “‘Look at this butterfly, what a frock it is wearing!” — she will find a way to say this to me, even in her physical absence. I will spot red velvet mites and bring them home for someone else.

Security is beyond money. Security is knowing that you will be okay. You will get destroyed but you will always find an anchor in your soil. A regermination and a rebirth. Nature is a permanent cinema of impermanent moments. As long as I am alive and capable of paying attention, I will appreciate mother earth with these eyes given to me by my mother. This is the inheritance, the insurance of wonder.