Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Charles Darwin had a knack for turning the world on its head. In 1859, On the Origin of Species provoked not just a crisis of faith but challenged the notion of a fixed hierarchy in the living realm, that humans “ruled them all”. In 1875, he shook that notion up again with his treatise on Insectivorous Plants. In it, Darwin offered shocking proof of a reversal of the “natural” order. He documented plants that consumed insects, small animals, even.

When a significant chunk of the human population suffers from plant blindness — the tendency to overlook plants in one’s everyday life — the scientific discovery of flesh-eating flora was bound to become sensational. And it did. Grotesque exaggerations (tentacled man-eating trees, sucking vampire vines, hissing snake-like shrubs) found their way into imaginations, news reports, and the arts.

Carnivorous plants are specialised flowering plants that supplement their growth through the capture and digestion of animals, usually insects. They evolved some 70 million years ago for a singular reason: to survive in nutrient-poor environments. These environments have plenty of sunlight and wet or waterlogged soil that doesn’t provide the essential nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) the plants need to grow. Since they don’t have to worry about sunlight, these plants can afford to develop modified leaves that are less efficient at photosynthesis, but excellent at acquiring the missing nutrients by capturing prey. So, while regular plants absorb nutrients from the soil through their roots, hunter plants get them through their leaves.

Many scientists believe that carnivory in plants is a “last resort” adaptation to surviving in poor soil conditions. This makes sense because the growth gains from prey nutrients must outweigh the energy costs of building traps and developing digestive enzymes. A plant will succeed as a carnivore only if the nutrients it captures from its prey can supplement photosynthesis and improve growth.

There are 800+ documented carnivorous plant species. Forty-eight species from five genera (Drosera, Pinguicula, Aldrovanda, Nepenthes and Utricularia) belonging to three families (Droseraceae, Nepenthaceae and Lentibulariaceae) have been reported from India. Each family reused old defence genes, turning them into their own special trapping mechanism. And voila! An armoury of leafy tricks, snares, lures, and traps that illustrate the marvels of botanical engineering. Indian carnivorous plants deploy four clever strategies to catch their prey: flytraps, snap traps, pitfall traps, and suction traps, as you’ll see below.

Flytraps

In plant families like Droseraceae, the trapping mechanism of choice is often called the flypaper trap, after the sheet of paper with a sticky substance that traps insects that land on it. Droseras or sundews prompted and catalysed Darwin’s research on carnivorous plants. Their long leaves (narrow in the case of Drosera indica, spoon-like in D. burmanii, and shield-shaped in D. peltata) have tall, mobile, gland-tipped tentacles that secrete sparkling drops of sticky mucilage. When an insect is drawn in by the glistening liquid and becomes stuck, the protein-sensitive outer snap tentacles get triggered. They bend down in a death embrace, preventing escape. The glands secrete acids and enzymes that eventually transform the whole animal into nutrient-rich fluid, easily absorbable by the leaf. (1) D. burmanii is incredibly sensitive to touch, ranking second only to D. glanduligera (an Australian species) as the fastest terrestrial predatory plant in the world.

All three Indian sundews grow in wet, infertile soils or marshy places. (3) D. peltata is the most widespread, growing throughout the plains and up to elevations of 3,000 m. (1) D. burmanni is found in eastern and Central India while (2) D. indica grows in open habitats of the western coast.

Sticky traps

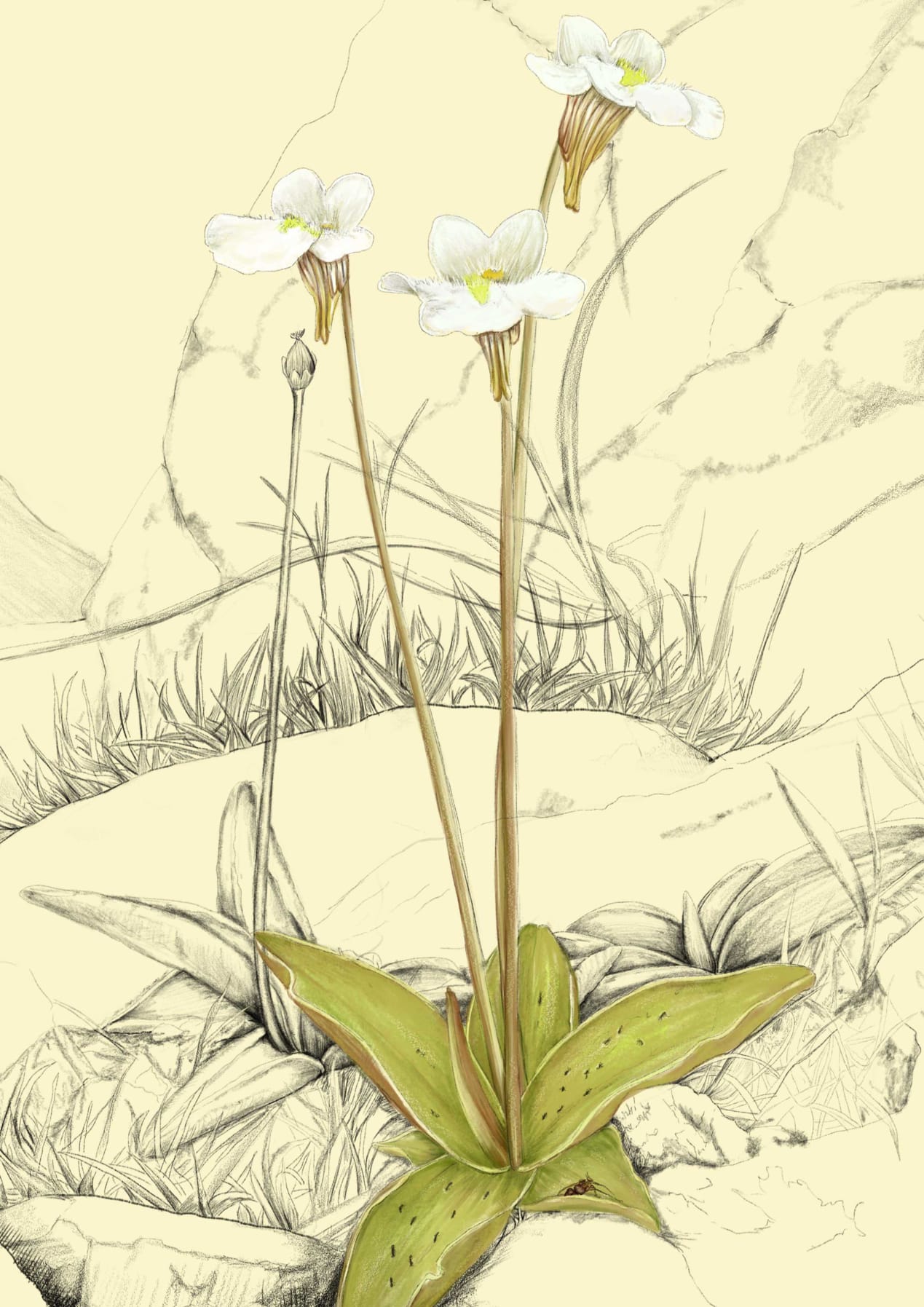

Alpine butterwort (Pinguicula alpina) is a temperate species, commonly found along streams in the cool, boggy alpine heights of the Himalayas. At first glance, it appears unassuming. But on closer look, its leaves are dotted with two kinds of glands: stalked ones that trap prey in a sticky mucilage and unstalked sessile ones that release digestive enzymes. Unlike sundews, its mucilage glands are quite short and discreet, belying their sinister function. Their mucilage is greasy, butter-like, which is the reason behind the common name — butterworts. In fact, pinguis in Latin means “fat”. Some cultures used butterworts to curdle milk, solidifying the buttery association.

Small insects alighting on the leaf stick in the mucilage. This prompts the sessile glands to release digestive enzymes, while the leaf blade curls inward, wrapping the helpless insect in more glands to speed up digestion.

Snap trap

The snap trap may be the most well-known trap of a carnivorous plant, thanks to the infamous Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula) and the creative imaginings of writers and filmmakers. Snap traps evolved from flypaper traps by becoming more mobile and extremely touch-sensitive. This carnivory arose when an old plant defence system called “jasmonate signalling” was adapted for catching prey.

India’s only snap trap plant is the waterwheel (Aldrovanda vesiculosa), a rootless, aquatic species that preys on tiny invertebrates. Although reported from brackish waters in West Bengal and parts of the Northeast, it may now be extinct there.

Stalked leaves are arranged in a whorl around a slender stem, giving the appearance of a wheel. The leaf blade is two-lobed, notched at the tip, with a central hinge. On the inner side of the trap lobes are plenty of sensitive trigger hairs. When set off, the leaves snap shut through a rapid movement called thigmonasty, closing in just 10-20 milliseconds. Any struggle only encourages the trigger hairs to seal the leaf tighter. The resultant “stomach” remains closed for a week or so, until the prey is digested and absorbed.

Pitfall trap

In pitfall traps, the leaf forms a pit-like structure filled with digestive juices that passively captures prey. Pitcher plants are iconic examples. Nepenthes khasiana, endemic to Meghalaya, is India’s only pitcher plant. It is a climbing undershrub whose pitchers are modified leaf blades. The pitchers are vibrant reds, greens, yellows, suspended from tendrils (adapted leaf midrib). Pitfall traps rely on lures to attract meals. The underside of the lid and the rim of the pitcher secrete a sweet treat, irresistible to a hungry animal. Once inside, escape is impossible thanks to the slippery, waxy inner walls. Near the pitcher’s base, digestive glands release enzymes which convert the unfortunate victim into an absorbable smoothie.

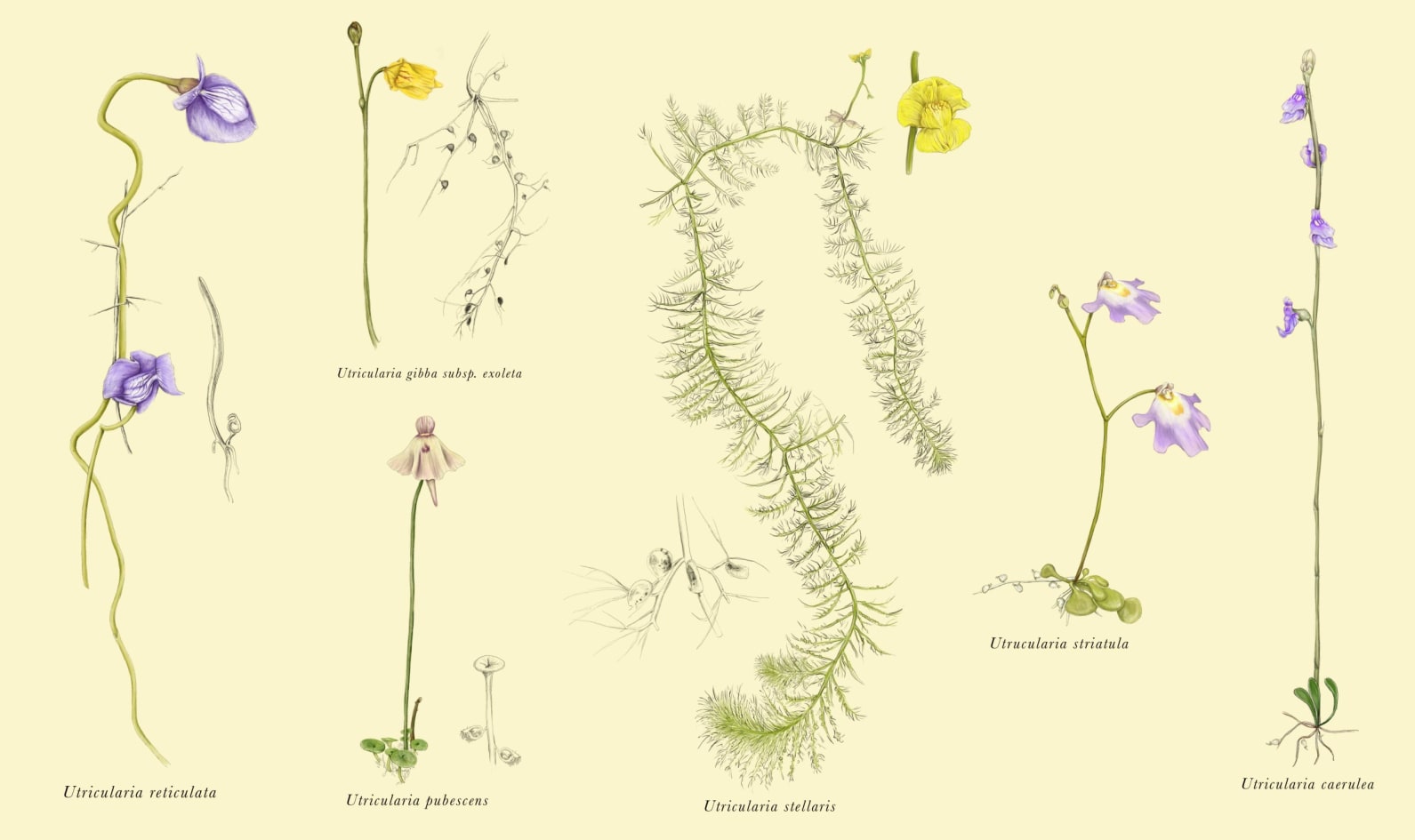

Bladder or suction traps are exclusive to the largest and most widely distributed carnivorous plant genus, Utricularia, also known as bladderwort. Bladderworts are fascinating, highly specialised species. Other than their gorgeous flowers, nothing about them is quite what it seems. They lack true vegetative parts — roots, stems and leaves. Depending on whether they grow on land (Utricularia caerulea, Utricularia pubescens, Utricularia reticulata), on other plants (Utricularia striatula), or in water (Utricularia stellaris, Utricularia gibba), Utricularias may have root-like rhizoids, stem-like stolons, or leaf-like organs.

Bladder traps, easily the most sophisticated plant structures on the planet, are generally attached to these vegetative parts, hidden from view. Bladders are stalked and have a “mouth”, an opening leading to the inside, lined with digestive glands. The mouth is fringed with trigger hairs and guarded by a door. Traps are “armed” when the bladder pumps out ions and water through osmosis, creating a negative pressure inside. This vacuum generates elastic tension in the bladder walls. When an organism touches the sensitive mouth hairs, the trapdoor springs open, suctioning in water and the prey. The door snaps shut once the bladder is filled. This entire sequence happens in milliseconds. The prey is digested and absorbed, after which the trap resets.

Bladderworts have a Guinness World Record as the Fastest Predatory Plant. While the majority of Indian Utricularia species are widely distributed, some are endemic (only found in some geographic areas and nowhere else).