Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Stare at a sea anemone for long enough, and you might find yourself hypnotised. Its colours are vibrant yet warm. Numerous long tentacles move gently, like people in a crowd with their hands in the air. Observing a sea anemone is a good antidote to managing chronic and acute stress. For instance, if you are unsure of where life is going, or perhaps you are in the middle of a difficult dive and feeling out of breath, watching an anemone can bring you peace. You start to blink slower, your breathing relaxes, and life in general starts to slow down.

Despite their therapeutic beauty, we do not look at anemones as often as we do the clownfish that live inside them. Sea anemones receive plenty of time in the spotlight but almost entirely to serve as an animated backdrop. Once we get past the tongue-twisting pronunciation of “uh-neh-muh-nee” and begin to acquaint ourselves with these enigmatic creatures, the world of sea anemones is a gift that keeps on giving.

Sea anemones are cnidarians, in other words, invertebrate animals known for their radial symmetry and venom-laced stingers. Corals and jellies are among their more famous cousins. Named after terrestrial flowering plants of the buttercup family, sea anemones are predators with a healthy appetite for plankton, other invertebrates, and even fish. There are approximately a thousand species of anemones inhabiting the shallow and deep seas, in waters cold and warm. Some live in colonies or partner up with other animals; several live on their own, half-buried in the sand, in crevices and tubes.

If you are new to the world of sea anemones, in this showcase you’ll find more than a few good reasons to get into your fins or even flip-flops and set off on a quest of these hypnotic wonders of the sea.

Anemones are known for their diversity in shape, size, and form. Some anemones like the magnificent anemone (Heteractis magnifica) (left) have a distinct trunk-shaped body that attaches itself to hard surfaces by an adhesive foot. The top of the anemone consists of an oral disc lined with stinging tentacles. The adhesive anemone (Cryptodendrum adhaesivum) (right), also called the pizza anemone for its crust-like edges, grows more like a flattened carpet.

Anemones can dramatically inflate and contract their bodies in response to environmental conditions. While they are sedentary and stay put in one location, they are capable of small movements. Photos: Vardhan Patankar (left), Samuel John (right)

Cover photo: Dhritiman Mukherjee

Sea anemones are closely related to corals, the majority of which live in colonies. Numerous coral polyps live fused to one another by their hard calcium skeletons. The mass of tentacles seen in anemones often gives the impression that they are colonial, too, but sea anemones are predominantly solitary.

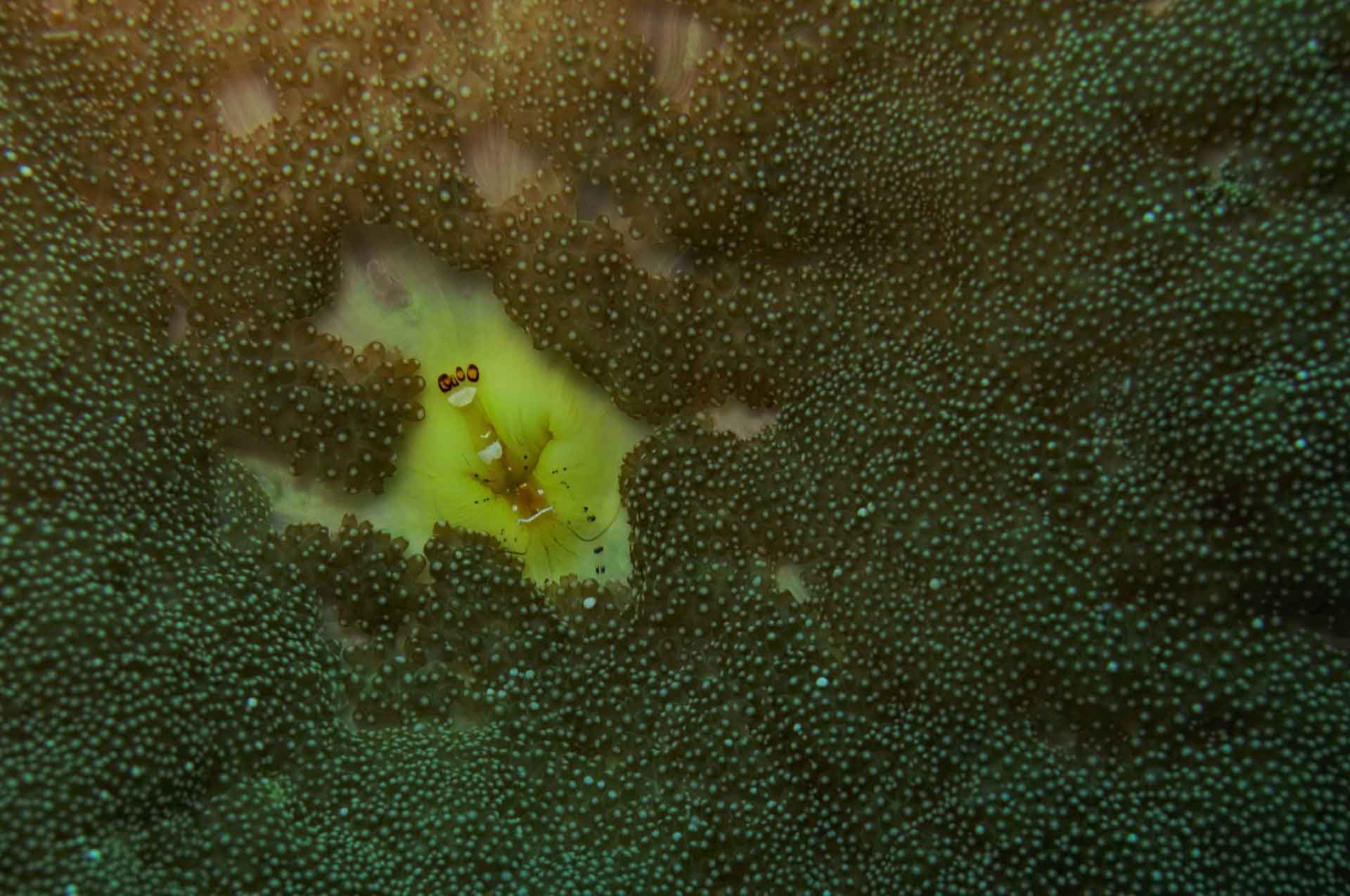

The entire anemone is a single polyp, and the tentacles cleverly hide an opening that functions as both mouth and anus (top). What anemones do share with corals is their symbiotic relationship with coloured microscopic algae that provide a significant portion of their nutrition. In addition to this constant supply, anemones also use their tentacles for hunting. At times their prey can even be a massive jellyfish! (above) Photo: Vardhan Patankar (top), Umeed Mistry (above)

Anemone tentacles come in a range of shapes and textures, from long tapering slender fingers to reduced knobs and textured branches to swollen clubs at the ends. Soft colour tones and gentle tentacle movements give anemones their ethereal appearance. Photos: Umeed Mistry

A remarkable exception to the otherwise solitary nature of sea anemones is visible in the gorgonian wrapper (Nemanthus annamensis). A series of polyps attach themselves to the base of whip coral and sea fans. Each has hundreds of tentacles spilling out from their oral discs. As they multiply, the polyps will gradually “wrap” themselves all along the body of the coral. Photo: Chetana Babburjung Purushotham

Tube-dwelling anemones (Ceriantharia) are another group of exceptionally beautiful tentacled animals, but they are quite distinct from the “true anemones”. These anemones construct tubes made of sediment, bound by their mucous and thread-like secretions (left). Anemones can retract into their tubes and subsequently retract the tubes into the rocky crevices or loose sand they call home. Tentacles are in two whorls and are typically white. Some have tentacles that are tinted in vibrant shades of neon, often within the same animal (right). Photos: Chetana Babburjung Purushotham

Tube-dwelling anemones that reside in sandy patches might choose to stay buried during the day and reveal themselves at night. With fewer predators active after dusk, tube anemones can feast on the exceptionally large smorgasbord of plankton that also emerges in the dark. Photos: Vardhan Patankar (top), Umeed Mistry (above)

Sea anemones have been found as deep as the Mariana Trench at about 10,000 m deep in the Pacific Ocean. They are also extremely common in habitats so shallow that they are exposed to air for a few hours each day. The intertidal zone of the ocean goes through dramatic but rhythmic changes in water level during the daily tidal cycle. Organisms in this region are adapted to extreme fluctuations in water, temperature, salinity, and oxygen. Some species of anemones like the carpet anemone (Stychodactyla) (left) and the pearly sand anemone (Paracondylactis) (right) are able to thrive in such environments. The anemones are most active during high tides, feeding comfortably when fully submerged. When the water recedes into low tide, the tentacles are retracted into the body, and the anemone goes through a short period of hibernation to stay cool and prevent drying up. Photos: Umeed Mistry (left), Sarang Naik (right)

Sea anemones are sedentary, lack eyes, and do not have a centralised nervous system to guide them through life. They rely heavily on venom-lined tentacles to defend themselves from predators and competitors as well as to capture, immobilise, and digest their prey. Prey could range from small to large crustaceans, molluscs, and fish. Anemones do not have a venom gland but produce venom with the help of ubiquitous nematocytes. Nematocytes produce venom packets (stinging cells) called nematocysts, containing a mixture of neurotoxins and actinotoxins, which will ultimately deliver the venom when discharged quick and powerful.

Anemones can cause rather painful burns and rashes in humans. They are not deadly but are bad enough to warrant avoiding any contact. The anemone in this image is breathtakingly gorgeous (with its soft coral-like appearance and pretty broccoli-shaped branches) and also capable of causing excruciatingly painful ulcers. It’s called hell’s fire anemone. Photo: Joydeep Sarkar

Sea anemones appear to have quite a few “friends”. Small fish like the clownfish, porcelain and swimming crabs, and numerous species of shrimps, all fit the ideal description of prey, but the anemone does not attack them. In fact, though these animals walk, swim through, and even live inside the oral disc of the anemone, they are spared the wrath of the tentacles.

Through evolutionary time, sea anemones have evolved a spectrum of symbiotic relationships with other marine species. The deal is rather straightforward. For instance, the carpet anemone provides a home base and protection from predators. In return, it gets regular cleaning services from peacock-tailed anemone shrimps and porcelain crabs, and metabolic waste from the families of anemonefish that shelter within it. Anemonefish may also help anemones lure other fish closer.

Each of these partners has evolved immunity against anemones. This is achieved using a coating of mucus that covers their bodies. Anemonefish are constantly swimming through the anemone, brushing past its tentacles, some of their most striking behaviours. While this may look like play, the fishes are actually constantly acclimatising themselves to their host anemone, reminding it not to fire off any nematocysts in their direction. Photos: Samuel John (top), Chetana Babburjung Purushotham (above left), Umeed Mistry (above right)