Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

The sal is a charismatic tree — communities of this lush green tree dominate large tracts of land, stretching endlessly along the Himalayan foothills in Uttarakhand. The peripheries of Pawalgarh Conservation Reserve, where I am walking with naturalist and local resident Naveen Upadhyay, host creatures big and small. “The Bachelor of Pawalgarh, one of the largest-known tigers, was shot by Jim Corbett in this very forest,” says Upadhyay. “The great slaty woodpecker, the largest woodpecker in the Indian subcontinent, is found in flocks here,” he says, listing the stars and legends of the forest. However, I am fascinated by a rather unassuming structure — a termite mound. Standing as high as my shoulder, the brick-red mound matches the leaf litter that covers the forest floor. I cautiously touch the powdery-looking walls. They are rough but surprisingly firm, like plaster. They also feel hollow, like a cast made of papier-mâché — sturdy yet oddly porous.

A few metres away, I spot another, and then another conical turret rising from the forest floor to form a colony of fortified soil castles. “Only a part of the mound rises above the ground; the real work happens underground in structures that are many times larger,” says Upadhyay, noticing my attention has shifted.

Once I return home to Delhi, I feverishly look for ways to think of termites. In 2020, a termite infestation pushed us to throw away most of the second-hand furniture we had bought to set up a makeshift pottery studio. The results of Google searches are, for lack of a better term, scary. And yet, they’ve captured my imagination. There must be another side to the story.

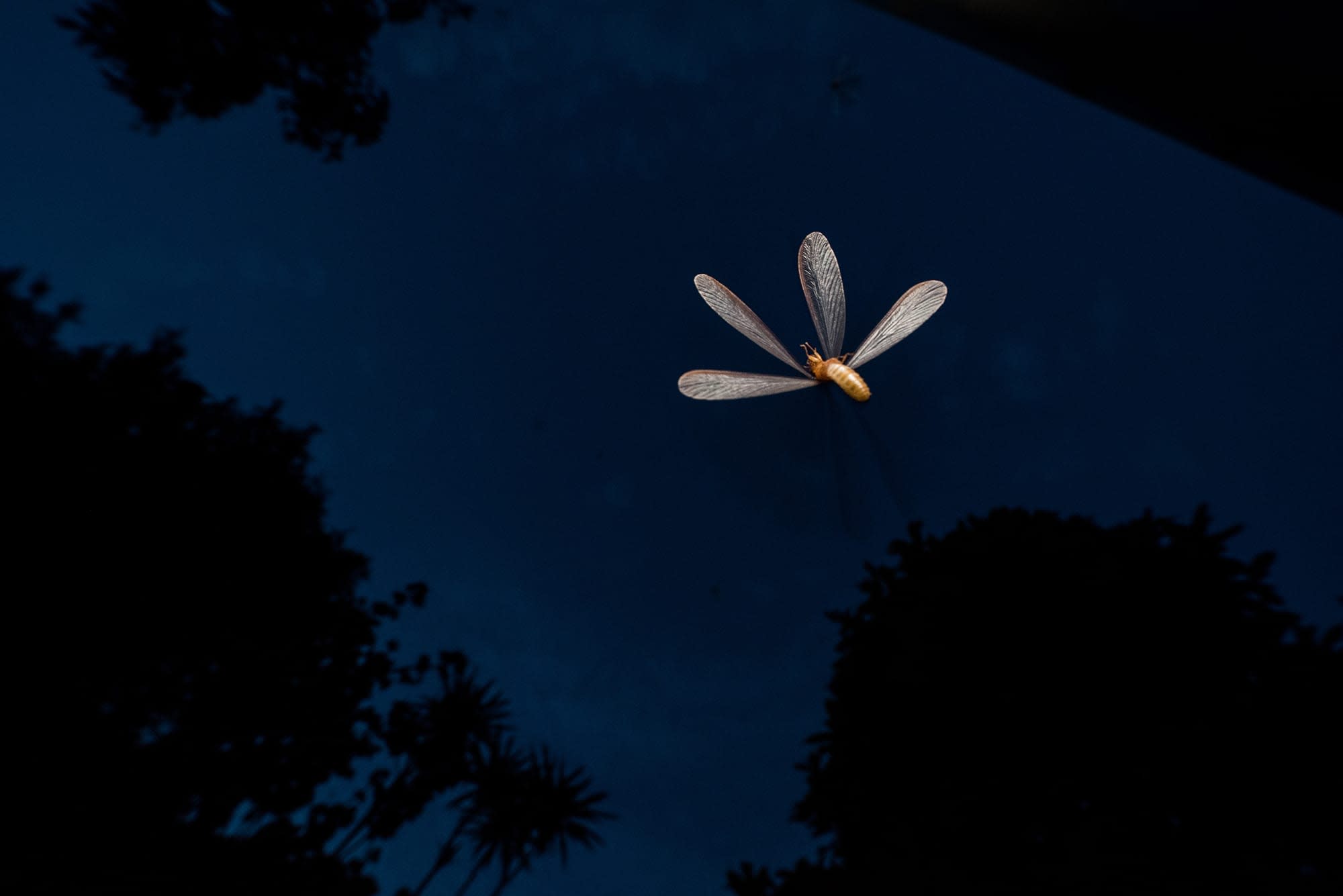

Cover Photo: Termites live in complex social structures organised in different castes. While the workers are responsible for food collection and construction, soldiers for protection, reproductive (also called alates) are responsible for growing the colony. Alates are the only termite caste with wings, so they can fly to other locations to start new colonies. This image is of the Coptotermes gestroi species. Cover Photo: Ripan Biswas

I speak to ecologist Joyeeta Singh Chakraborty over a Zoom call to understand termites better. Chakraborty, who studied termites in the moist sal forest of Doon Valley, is fascinated by termites. “It is amazing how thousands of these tiny creatures can communicate, coordinate, and build such enormous mounds. They act as a single supra organism,” she says. She confirms there are over 3,000 species of termites in the world, and India might have over 300-400. Not all build mounds.

Many species live in wood, and several more live in the soil. What I saw in the sal forest, Chakraborty confirms, is an architectural marvel by a mound-building termite called Odontotermes obesus, a species commonly seen across tropical forests in India. However, this is only one of the many skills this maligned termite possesses.

Architects

A mound, called termitaria, built by O. obesus sp can reach up to three metres in height or as tall as an Asian elephant, but a single termite is as small as an ant. However, what we see, is the tip of the iceberg and only a part of the story. The structures above ground are porous, temperature-controlled ventilators that aerate underground nests many times their size. The termites have a built-in chimney, connected to a network of vents and tunnels, that circulate air and control the temperature. Entire termite cities with millions of residents, chambers, tunnels, and fungal gardens thrive beneath.

The mounds are sturdy and can withstand torrential rain and harsh sunlight, standing tall for years. Surprisingly, they are all built with a bio-cement that is a concoction of termite saliva and termite excreta in most cases. How does a structure like that stay strong?

An interdisciplinary project by the Centre for Ecological Sciences and the Department of Civil Engineering at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru, studied the strength and stability of a mound and the materials used to build it. Their research revealed that the mounds were intricate bi-layered constructs — stronger, thicker walls protected the core, while thinner, more porous walls formed a shell around them. The researchers argued that this performed a dual function — the inner walls lent stability and strength to the mound, while the porous outer walls ensured it was well-ventilated.

These sophisticated mound designs have inspired architects across the world. One of the most famous examples is a shopping centre in Harare, Zimbabwe that uses tips from termite mounds to regulate the inside temperature.

Farmers

Ventilation and temperature control are essential for the termite species’ core activity — farming. O. obesus sp does not feed directly on wood but exclusively on fungi farmed in its underground chambers. Each mound contains chambers where worker termites cultivate “fungal gardens” by feeding resident fungi dead plant material that they gather from their surroundings. The fungus is cultivated on the termites’ collected faecal matter, also called a “comb”. The relationship is mutually beneficial — the termites receive food, while the fungus gets a temperature-controlled environment to thrive in.

Not all fungi are good fungi. Parasitic fungi are known to invade these gardens. However, the termites are prepared. A study published by researchers at IISc in 2018 argues that the visually challenged termites sniff the invaders out and bury them alive.

Hosts

While parasitic fungi are swiftly buried alive, other creatures find shelter in live or abandoned termite mounds. Bengal monitor lizards often reuse abandoned mounds. Young monitor lizards, especially, use them for protection from predators and as a temperature-controlled chamber to rest in. Snakes are also known to shelter in termite mounds. In Hindu folk mythology, a termite mound is believed to be the entrance to the world of snakes called Bhogawati, a place that many Hindu communities worship.

Ecosystem Engineers

One of the most significant roles termites play is that of nature’s recyclers. In diverse ecosystems, from forests to grasslands, termites are, what scientists call, ecosystem engineers. “Termites can significantly modify their environment and influence several species living within it. They can engineer entire ecosystems, and their collective impact can extend across landscapes,” says Chakraborty. In their ecosystems, they chomp on dead wood, dry leaves and other dead matter and keep an ecosystem clean. In the process of building mounds, they aerate and alter the condition of the soil. In Africa, studies in the savannahs have shown that they create “hotspots of fertility” where rich vegetation grows. However, studies in India are yet to establish how termites help in soil regeneration and the growth of plants.

Termites are also an excellent food source for various animals and birds — from grey-headed woodpeckers to snakes and monitor lizards. They sustain several species around them.

Pests

The dark side of the termite world is that most are opportunistic, voracious feeders of timber. Wherever they exist in large populations, they can attack the structural timber of buildings, trees in forests, and crops. Entire towns and agricultural yields have suffered from termite damage. In India, Heterotermes indicola is one of the main species to cause structural damage with substantial impact. About 10-15 per cent of all termite species can be termed pests for the harm they cause to human-made landscapes. However, even the termite species that are harmless in natural ecosystems (like the mound building O. obesus), may turn into opportunistic pests in the absence of sufficient leaf litter or dead plant matter. In such cases, over 60 per cent of their food resource can come from crops, fresh wood, or leafy materials of live trees. “One way to look at O. obesus is as a pest, but the destruction they cause is largely a sign of degrading forests,” says Chakraborty.