Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

India has many legally protected areas like national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, conservation reserves, and community reserves. We have sacred groves, without legal protection, that are protected by communities based on religion, tradition or purely utilitarian basis. There are also small biodiversity areas that come under the Biological Diversity Act, and Heritage Sites and Ramsar sites protected on the basis of biological wealth. We also have some areas protected for their geological importance based on their unique landforms or geological features.

The USA has numerous areas protected as “Geoheritage” sites. Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, is surely the most famous of these. Its spectacular scenery was created by the Colorado River eroding 447 km of enormous gorges and canyons, beginning around six million years ago. Millions of tourists visit the Grand Canyon every year. In India, we have geoheritage sites too, but by and large, they are neglected and unappreciated. For instance, in Andhra Pradesh’s Kadapa district, the Pennar River has cut the stunning Gandikota Canyon. While the Pennar is not as large or sinuous as the Colorado, it is nonetheless spectacular. In the same district, you’ll find Belum Caves, formed millions of years ago as water cut through black limestone deposits. We also have extraordinary cave formations with endemic fauna, in the Western Ghats, Central India, the Aravallis, Northeast India (particularly Meghalaya), and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, but they are out of the radar of conservationists, and even governments.

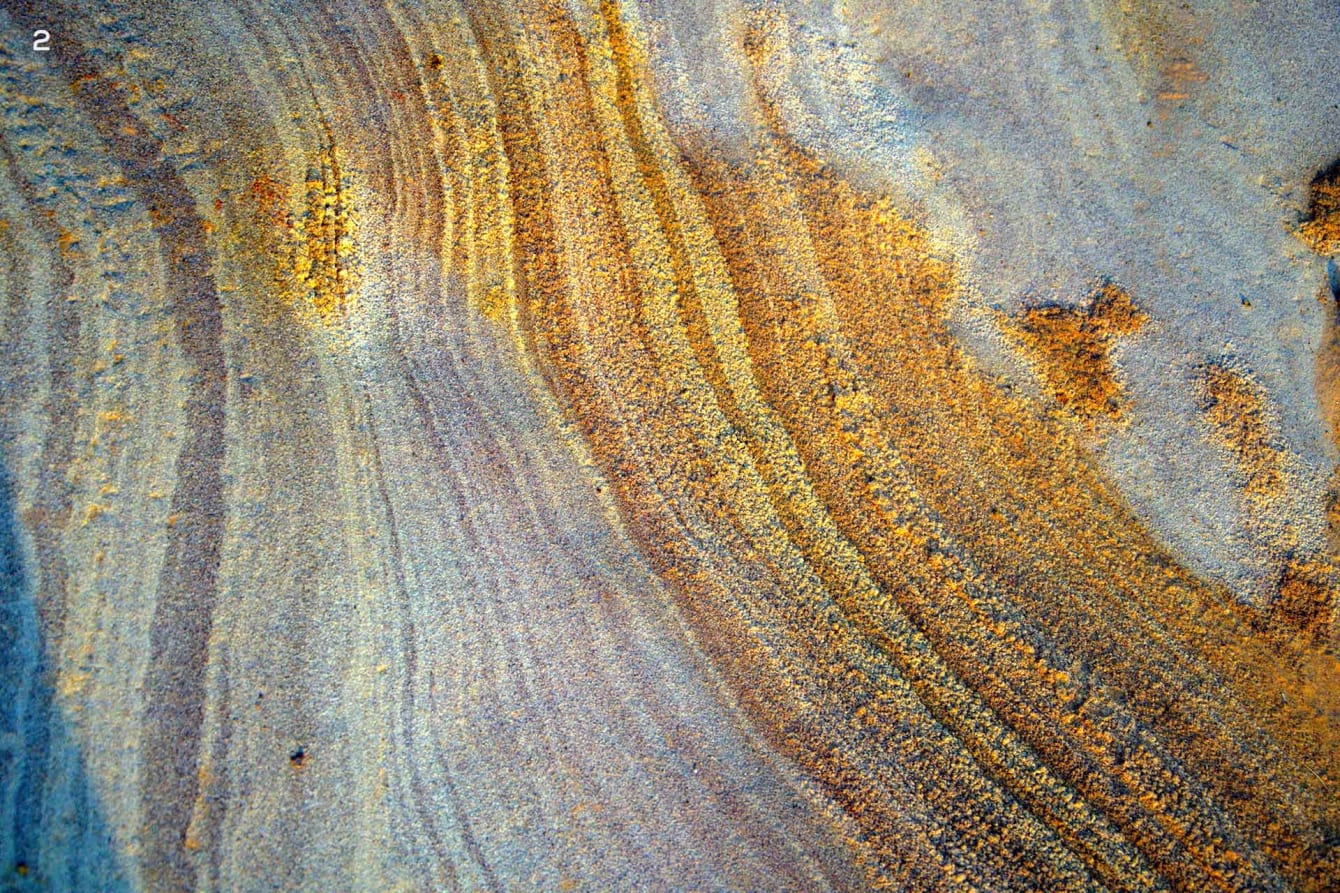

Cover photo: About 70 km from Bhuj in Gujarat’s Kutch district, the Lyari riverbed has fascinating prehistoric rock formations that in parts look similar to the rocks of the Grand Canyon in Nevada, USA. Photo: Dhritiman Mukherjee

A few years ago, I visited a stunning dry riverbed of the Lyari (Liari) river, in Gujarat’s Kutch (Kachchh) district and was amazed by the beauty of its rock formations. Water runs in this riverbed only when this dry region receives good rainfall. For most of the year, it remains dry. Lyari is about 70 km from Kutch, near the famous Banni Grasslands, behind Dhinodhar hill, which at 384 m is the second highest peak in Kutch district. Dhinodhar is a landmark of the area, and famous for its rich fossil beds.

Millions of years of weathering created spectacular rock formations on the Lyari riverbed. The surrounding landscape, relatively untouched by development, consists of scrub forests (on both banks).

Consulting some papers on geology, I found that Dhinodhar Hill is an old volcanic plug. In simple terms, a volcanic plug (volcanic neck or lava neck), is created when magma (molten lava) hardens within a vent of an active volcano. The plug is composed of a closely spaced cluster of basaltic hills, among which the Dhinodhar peak is the highest. The drainage lines from the hill have developed a radial pattern, and the steep hill slope is covered with scree of cuboidal blocks of basalt.

The Lyari and other such ancient rivers and the surrounding hills are full of fossils that need immediate protection before the wave of so-called development takes over. Banni Grasslands is already under tremendous pressure — I was told that solar panel parks are planned in 5,000 ha of grasslands, near Kiradungar, a hill with extremely rich fossil beds. Windmills are coming up everywhere, and we are not far from mining starting up. Unless some sort of legal protection is given to these Geoheritage sites, we will not even know when stones of the Lyari River will be auctioned off. These areas are an important part of our country’s heritage.

When I met Dr Subhash Bhandari, Head, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, KSKV Kachchh University, Bhuj, he expressed deep concern about the changes that are coming up in Kutch (Kachchh) and the land grabbing that is underway. While many conservationists speak on behalf of wildlife, who will speak on behalf of ancient rocks and fossils? It is time for India to look after its geological heritage!

Dr Bhandari sent me a scientific paper titled, Terrestrial Martian Analog Heritage of Kachchh Basin, Western India, by Anil Chavan, Subham Sarkar, Adarsh Thakkar, and 12 other scientists working in eight institutes, published in a prestigious journal Geoheritage (2022). They write, “The Kachchh Basin is a peri-cratonic rift basin in western India, exposing a vast range of diverse geologic features representing the past 200 million years spanning from the Jurassic Period to the recent… This basin has preserved several classical terrestrial analog sites to study planetary science. Several potential localities in the basin provide opportunities to explore as Martian analogs.” The authors recommended five sites from the Kachchh basin that have preserved classical geomorphic features that need to be protected as geoheritage sites, and “need strong attention for conservation.” They further write “the establishment of geoparks and development of geotourism in the proposed area will enhance the Earth and Planetary Sciences scenario apart from boosting of local economy, including helping activities, research funding, and employment opportunities for locals that will play a significant role in the economic development of the region. To achieve such an ambitious program and accomplish the Sustainable Development Goals, these locations should be conserved and extended for geotourism.”

We all know of ecotourism based on national parks and wildlife. Let’s add geotourism to the options and let Lyari River lead the way.