Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

When we moved into the third-floor apartment, our terrace was large and lifeless. First, we brought a money plant and an arrowhead plant from a nearby nursery. Then, in a broken bathtub, we planted champa, mogra, raat ki rani, and painted the bathtub red. A small chikoo tree appeared from somewhere, and soon after, an old lady from the hills joined our household. Homesick for her natural habitat, she spent most of her time on the terrace, and declared one day, “The maali is useless. I’ll tend to the plants.” She brought seeds from her village, and next to our basil and kadi patta, she planted chilli, garlic, marigolds, and lai saag.

Other characters include bees, wasps, mosquitoes, a krait (which we discovered under our bed one night just in time), rats (which our dog Rani hunted), and flocks of birds. Crows, parakeets, mynas, black kites, and, countless pigeons.

When your home sits at the centre of a triangle, flanked by a flyover, a cinema hall and a booze shop, it is hard to forget that Delhi is a loud, angry place. Our acquisition of living things has been an attempt to do just that. Now, eight years since we first moved in, the terrace is a sanctuary.

It is also, unfortunately, a nuisance.

The house has inadequate storage space for a family of five (including seven-year-old twins and Rani). Whatever we cannot accommodate inside but will not discard, ends up on the terrace. There is an inverter, a washing machine, two clothes’ stands (always full), buckets and mops and other cleaning supplies, a ladder, and at any given time, a random assortment of toys. And did I mention the pigeons?

Where several species of birds have lost their habitats to urbanisation, rock pigeons have adapted and thrived.

By no means picky eaters; they consume insects, seeds, or really anything left behind by humans. Their natural patterns of flight, which evolved for their original cliffy habitat, are just as well-suited to the crevices in tall buildings. Fixtures of urban life, such as ledges and the back of air-conditioners, appeal to them as accommodation to the point that if they were suddenly transported to a forest, they would be out of place.

It helps that they breed throughout the year, but perhaps the most significant factor in their staggering rise in numbers – an estimated 150 per cent increase after 2000 – is their ability to evade predators. Their quick, vertical take-offs and sudden changes in direction allow them to escape without wasting any time.

The manic energy of the city below that I was keen to escape is recreated on our terrace by the pigeons every day. They eat our marigolds and drop green blobs on freshly washed white shirts. Sometimes I wish they would find another spot, but they find my terrace hospitable. It has everything they need: sun and shade, concrete and twig, food and water.

Early one morning, we woke to the sight of an injured pigeon in a shaded corner of the terrace. It cooed softly, thrusting its head forward as it limped one or two steps at a time. The kids and I watched it from the window while we ate breakfast. We put out some water for it. It seemed calm when it had the terrace to itself, so we tried not to disturb it. But the day had begun, and the terrace was our passage in and out of the house.

I took Rani down for a walk, the kids left for school, the bell rang all morning. Trapped on the ground, the pigeon seemed terrified whenever there was sudden movement. It would rush back into its corner and frantically flutter its wings but could not take off.

After the domestic rush of the morning subsided, I decided to let the bird have the terrace. I tried to get some work done while Rani slept at my feet, but my attention kept drifting towards the pigeon. Its iridescent plumage, the purple and green feathers on its neck, changed colour each time it moved. It was a sight I had seen a hundred times before and registered as fact but never quite as a thing of beauty. I watched as it took bites from the edge of a leaf. It challenged itself to do more, steadily increasing the number of steps it could take from one or two to four, five, six.

As someone who speed-walks past flowers in bloom, more concerned with the cerebral podcast in my ears than springtime in Delhi, this was a welcome change of pace. My attention held hostage by an unremarkable city bird.

Pigeons can divide a room. There are those who consider them family, and the act of feeding them spiritual and prayer-like. And then there are those who plant poison or install mesh on their terraces to keep them away.

When the twins got home from school, the first thing they did was check on the pigeon. They were excited to see it was still there. Then they quickly grew concerned. The full school day had passed and the bird had not found its wings.

Its condition had been improving through the day, I assured them, and by evening – maybe by the time they woke up from their nap – the pigeon would be ready to fly.

Pigeons can divide a room. There are those who consider them family, and the act of feeding them spiritual and prayer-like. And then there are those who plant poison or install mesh on their terraces to keep them away.

They are called all kinds of names. ‘Pests’, ‘sky rats’, ‘rats with wings’. This reputation is owed to the damage they cause to roofs, the corrosive quality of their droppings, and the unfortunate truth that they are carriers of serious pathogens.

These faults, though, seem to ignore their intelligence. They have strong memories, an understanding of abstract concepts such as space and time and are capable of pattern recognition and associative thinking. They can distinguish between different humans and even bond with them. I wondered what our guest made of us, if it could tell that we were rooting for it.

The afternoon was calm. The kids napped, Didi took her break, Rani slept on the rug. My friend cooed outside and moved less tentatively than before. Then the sun became softer and it was evening. Our usual routine kicked in. Runi left for dance class. Juni sat with me in the study and ate fruit.

There are two things Didi does as soon as she returns from her break in the evening – takes Rani for a walk and makes herself a cup of tea. Like always, she entered the house, left the door open behind her and went into the kitchen to boil water. Later, she went to the terrace to put Rani’s leash on. That’s when I heard her scream.

A soft-spoken woman, I had never heard her voice at that pitch. “No Rani”, she begged, again and again.

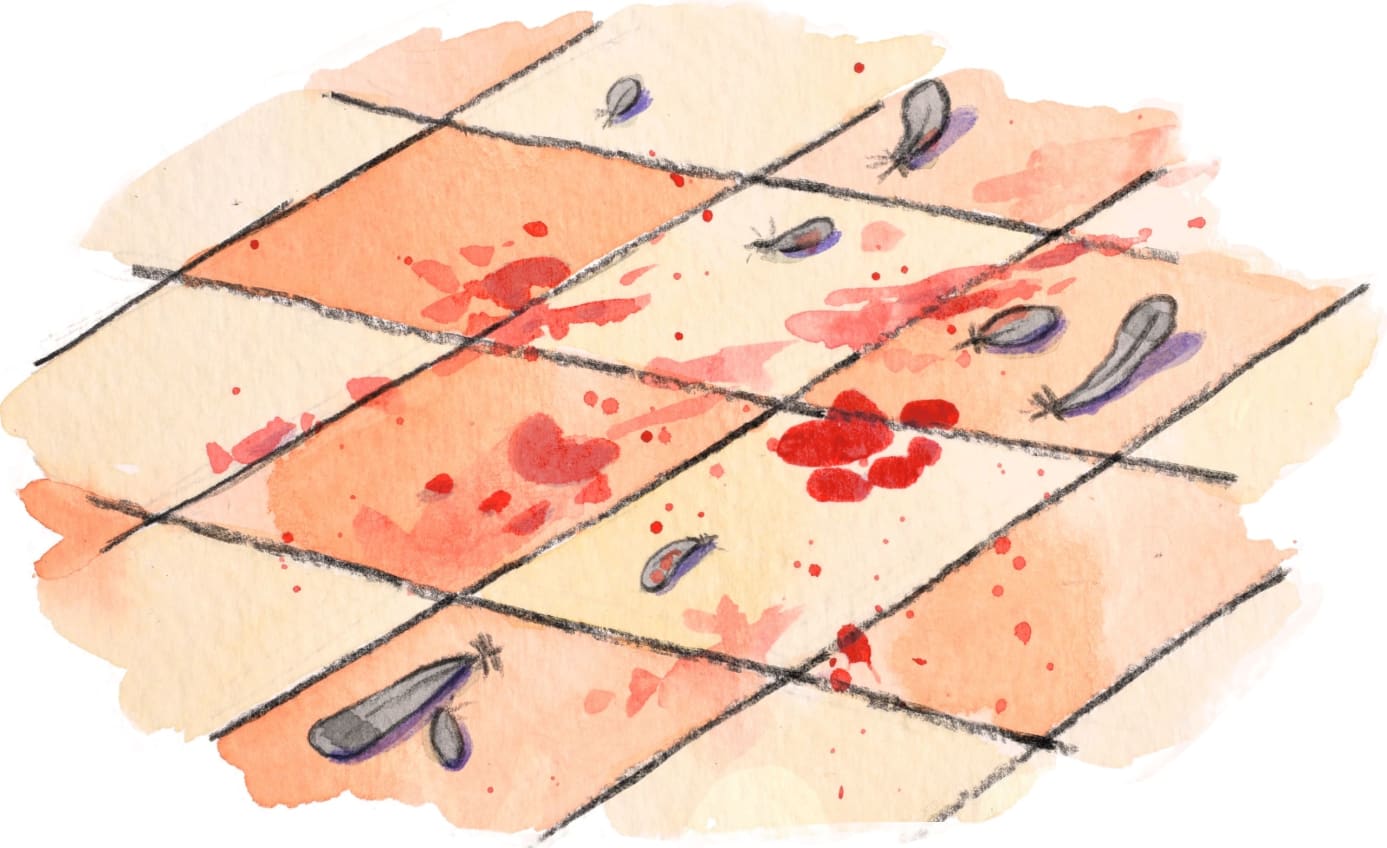

I instinctively played something on my phone and handed it to Juni so she would not follow me. Didi pulled Rani off and took her down. On the terrace floor there lay a trail of blood and feathers, and a few feet away, the bird. It lay on its back, its beak opening and shutting in slow motion as it tried to raise an alarm call. No sound came from its mangled face.

I came back and locked the door behind me. “What happened, Papa?,” Juni asked. “Oh nothing, Rani’s just being naughty,” I replied. My trusting daughter went back to her bowl of fruit. I could not bear to pick up my fork.

Rani is at least half hound. She digs the tiles as if they will give way to fresh soil. She leaps into the air to catch pigeons. Perhaps I should have known that an unsupervised Rani is a wild animal, and that on our terrace, a pigeon is nothing but prey.

Didi and I reached a silent understanding — she would remove all trace of the hunt while I kept Juni distracted in the study.

The stories children find compelling often have strong moral lessons at their core – greed, kindness, good, evil. Stories that clarify nature, though: evolution, the food chain, the instinct of one animal to hunt another, these do not measure acts in the wild by a moral scale.

These are less compelling, and indeed less digestible, for a six-year-old. I was not going to explain to the kids that their loving dog had killed that helpless bird, and that nobody was right or wrong.

Runi came home and both realised that the pigeon was gone. I acted as surprised as them. It must have flown away, I suggested. They agreed.

The kids went to the park. I left the house to run some errands. When I came back home, Juni was lying on the terrace next to Rani with a wet towel in her hand. She wiped her paws and picked out tiny feathers from in-between her claws. Pink drops fell to the floor as she squeezed the towel. Horrified, I asked Juni what she was doing. And with a smile on her face, she said, “Papa, the pigeon didn’t fly away. Rani ate her up.”