Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

It had been raining for hours. The kind of rain that made everything stick to skin, boots, thoughts. We were tracking frogs, but the calls had quieted, and most of the team was walking in that familiar monsoon silence — heads down, eyes scanning, not really talking.

I was behind the others when someone up front muttered, half-seriously, “Mushrooms chamak rahe hain”. At first, I thought it was a joke. Something tossed out to make the leeches feel less annoying. But then the trail dipped, and I saw it. A faint, greenish glow at the edge of a fallen log. Soft. Persistent. Not bright enough to startle, but just enough to stop me. I crouched down. The light was real. And alive.

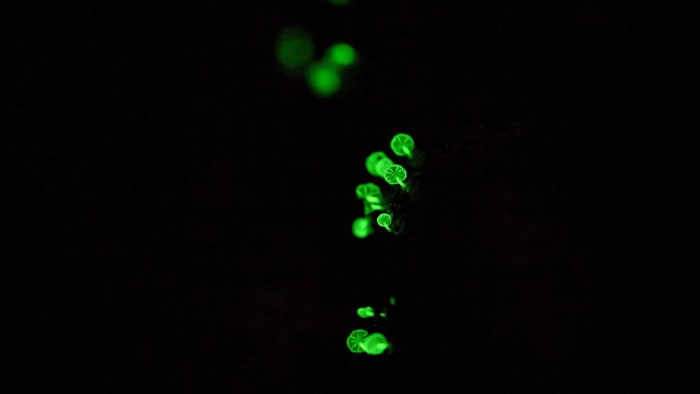

This cold, biological light is known as foxfire. It is from a species of bioluminescent fungi found in Bhagwan Mahavir Wildlife Sanctuary, Goa. Photo: Omkar Dharwadkar

Bioluminescent fungi aren’t rare in tropical forests, but they’re very easy to miss. They show up during the monsoon, often on decaying wood — logs, stumps, or sometimes even dead leaves. Most documented species in India belong to the Mycena genus, a group of saprotrophic fungi that specialise in breaking down organic matter. Some of them emit visible light. What I saw was one of them.

The glow is called “foxfire,” which sounds really cool on its own, but is rooted in chemistry. Inside these fungi, a pigment called luciferin reacts with oxygen in the presence of an enzyme called luciferase. The result is cold, green light — no heat, no waste, just glow.

While we know how the glow occurs, no one is completely sure why it does. There are a few theories. One says the glow might attract insects such as tiny beetles and flies at night, which then carry its spores elsewhere, helping the fungus spread. Another theory proposes that bioluminescence might act as a deterrent, signalling the fungus is unpalatable or toxic. Some scientists think the light might be a side-effect of how fungi manage stress while breaking things down — like a pressure valve for the chemical mess of decomposition (scientifically, oxidative stress management).

The truth? We’re not sure. It could be all of the above. Or none. That’s the thing with fungi — they don’t always reveal their secrets. But on that trail, with the forest holding its breath around me, the glow felt intentional, magical, and not a mere chemical byproduct.

Fungi aren’t the only organisms that glow. Bioluminescence has evolved independently over 30 times across the tree of life — in deep-sea fish, jellyfish, fireflies, even some millipedes. But within the fungal kingdom, the glow tells a story of a single, ancient origin. While this ability has since diversified into several distinct evolutionary lineages, all known glowing fungi trace back to one common ancestor. It’s a trait that persisted, branching and adapting over millions of years.

Take Mycena chlorophos, a well-known glowing species found across a wide range, including Southeast Asia, India, Australia, and Brazil. Its glow can be quite faint, requiring near-total darkness for the human eye to perceive. In Brazil, the giant Neonothopanus gardneri glows continuously throughout its several-day lifespan, appearing brightest under the cover of night. Though found on different continents, their shared presence within the same narrow evolutionary branch points to a single, ancient origin for this trait. This is a key distinction from organisms like fireflies or deep-sea creatures, for whom the ability to glow evolved multiple times independently.

Fungi rarely make it into the conversation around wildlife. They’re not charismatic, not noisy, and they don’t appear in camera trap photos. But they are everywhere — in the soil, on tree bark, inside roots, and sometimes, glowing under our feet. Globally, over 130 species of fungi are known to glow, most of them in tropical regions. In India, species like Mycena chlorophos, Panellus stipticus, and others have been documented in the Western Ghats and Northeastern forests. These fungi are sensitive to disturbance and often restricted to undisturbed, moist habitats, making them sensitive indicators of specific microhabitats. They show up when the conditions are just right: high humidity, decaying organic material, and the absence of artificial light. Even then, their glow isn’t always visible. You need complete darkness. You need to stop moving. And most of all, you need to be paying attention. That night, I almost missed it. I had walked right past the log. It took a pause, a moment to catch my breath, for the light to register.

In cities, we’re surrounded by light that never leaves. Tube lights, phone screens, passing headlights, always on, always pushing. But this wasn’t that. The glow I saw didn’t fill space. It didn’t demand a reaction. It was just present.

It existed because everything else had stopped. Because the torch was off, the noise had dropped, and the forest — for a moment — had gone back to its original settings. I looked closer. The log was beginning to fray at the edges. Layers of bark had softened into a dark mulch. Tiny threads of mycelium crept between cracks, a web dissolving the wood from within. And at its edge, the glow: pale, mint-green, barely rising above the wood’s surface. Not a flame. Not even a spark. More like a breath.

Their work is the essential business of decay. As saprotrophs, these fungi are nature's recyclers, dismantling the forest's fallen trees to unlock nutrients for new life. What looks like an ending is, in fact, a transformation. The light is a reminder that this process isn’t just functional; it can be beautiful.

We didn’t see any frogs that night. The rain returned, heavier than before. Our torches picked up water droplets, but not much else. Still, my eyes kept drifting to the forest floor. Looking for more light. I didn’t take a sample. I didn’t photograph it. Sometimes, it’s easy to think of forests as static. As green backdrops for louder stories. But that evening reminded me that they are full of slow, patient life — life that doesn’t need to be dramatic to be seen.

Bioluminescent fungi don’t demand attention. They don’t flash, roar, or chase. They glow, faintly, steadily, in the dark. And if you’re quiet, or lucky, or just walking a little slower than usual, you might see them too. A small, soft light. A reminder that even in decay, the forest keeps speaking. And that sometimes, even a mushroom can see you first.