Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Birds are capable of amazing feats. Arctic terns migrate from one pole to the other and back in a single year. But that’s nothing compared to what birds have achieved in folklore. Legends of their heroics explain how ancient people interpreted bird behaviour and how that has played a pivotal role in our perception of them.

Symbols and Omens

If the owl’s hypnotic gaze has ever made you feel that the bird can see your darkest secrets, you’re not alone. According to the Greeks, owls possess magical inner vision. The little owl that accompanied Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, led them to associate the bird with wisdom and knowledge. An owl flying over Greek soldiers was taken as a sign of victory. But after an owl is believed to have foretold the death of Julius Caesar, Agrippa, and Augustus, its hoots on dark nights sounded more malevolent than a wise, visionary nocturnal bird’s haunting call. Ancient Romans soon began to regard it as a sign of death.

Another bird blacklisted as harbinger of death is the carrion eating, raven. In Swedish and German folklore, ravens represented the ghosts and souls of people murdered or damned. And in Celtic mythology, when the Irish war goddess Morrigan visits the battlefield, she transforms into a raven.

God’s Messengers

Ghosts aren’t the only ones to seamlessly move between spiritual and earthly realms. Birds do it all the time, especially falcons who romance the upper skies. The Peregrine falcon might be renowned for its breathtaking hunting stoop, but Native Americans believed this raptor lives among the sun, moon, and stars. For its celestial powers, it’s perceived as god’s messenger.

But the vulture, despite being a scavenger, assumed a similar role in Egyptian lore. It’s believed that when these flesh-eating birds devour the dead, they also consume the soul. So, when they take to the sky, they carry with them the departed soul to realms beyond. The vulture is also sacred to mother goddess, Mut and goddess Nekhbet of Upper Egypt.

Saviours of Mankind

In various folklore birds are considered god’s faithful servants, and entrusted to perform vital tasks. The blood pheasant mentioned in Vanya and Ajeya Jha’s book, Ethno – Ornithology of Lepchas of Sikkim, is a story of the mother goddess Na-zong-nyo of the Lepcha people, who chose a bird to guide her people to safety after the rivers Rangeet and Teesta caused a great flood inundating their homeland. According to the legend, the blood pheasant drinks up the flood waters and saves the community

And according to Siberian folklore, the first shaman was an eagle the gods sent to heal mankind’s sickness and suffering. But unable to communicate with humans, the eagle was forced to mate with a woman. Shamans are believed to be descendants of this conjugality. And like the eagle that can travel between realms, shamans in Finland are believed to be blessed with similar power.

Spells and Curses

Birds connect humans to nature. They’re also our only chance to sight nymphs and gods in our own backyards. According to Roman mythology, when the witch Circe tries to tempt king Picus, the devoted husband of Canens, he turns her affection down. The spurned sorceress then changes him into a woodpecker. And when Hera, the Greek goddess of women and marriage, finds out that Zeus’s love for Io is the outcome of Iynx’s spell, she turns the nymph into a Eurasian wryneck. These tales lead to woodpeckers being associated with magic and spells.

In the Irish legend, The Children of Lir, Aoife, a jealous stepmother, curses the four children of Lir, the God of the seas, turning them into white swans. While the spells would last for hundreds of years, she lets them keep their voice. When Lir meets his children, they convey their fate to him through a song. The idea that swans sing at the end of their lifetime is believed to have originated from here.

Plumage and Bird Deeds

Ever wonder why some birds have the most extraordinary plumage and others such drab plumes? If legends are to be believed, the plumage of some birds is the outcome of their deeds, or rather misdeeds. When the Greek god of prophecy, Apollo, sends a white raven to spy on princess Coronis, the unsuspecting bird reports back with evidence of her unfaithfulness. Enraged, Apollo chars the tattletale’s feathers, and the raven’s plumage turns black.

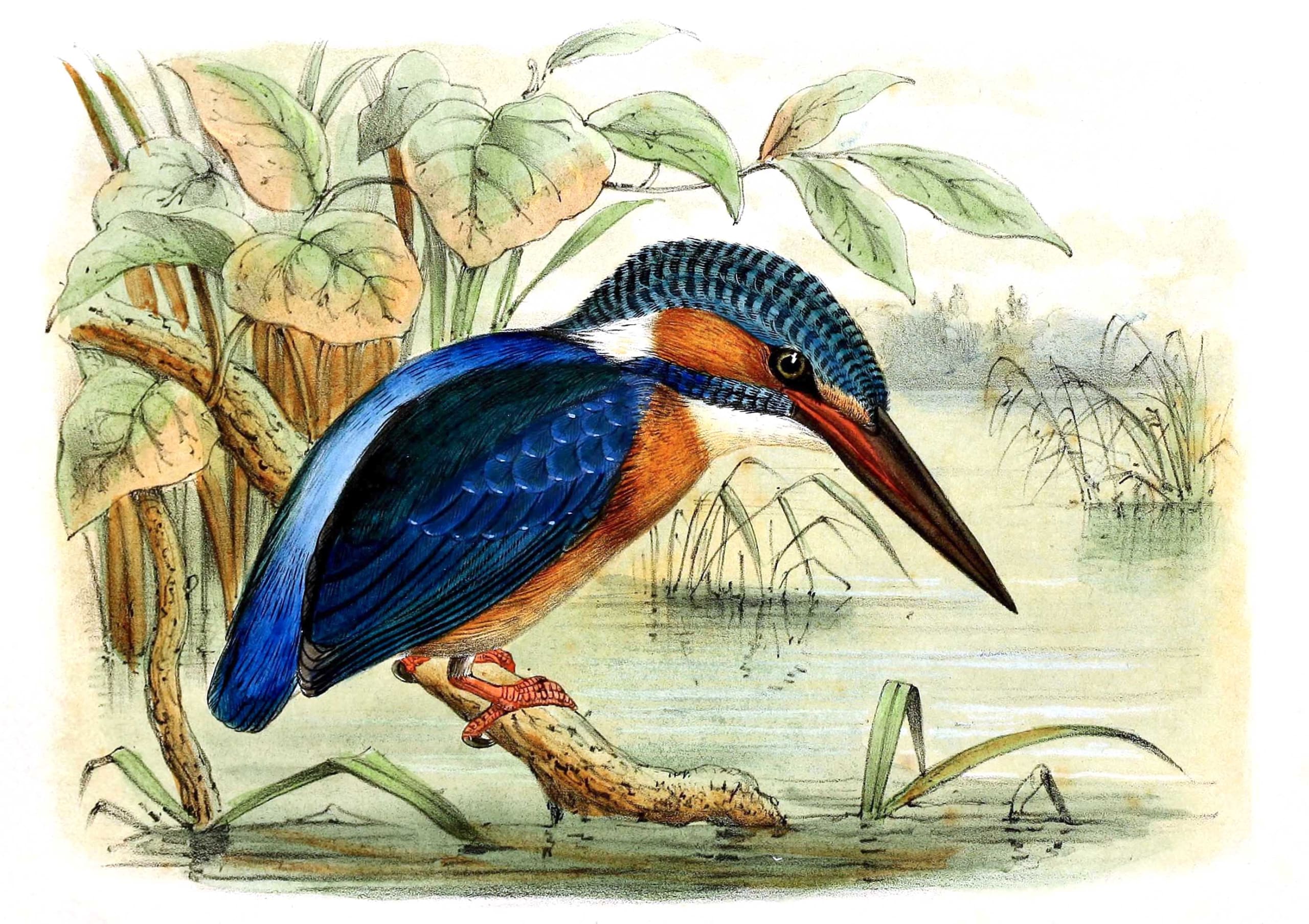

And the bird William Henry Davies immortalised in the poem, The Kingfisher, was once a grey bird. In the book, West Country Tales, by Johnny Kingdom, when Noah lets the kingfisher out of the ark to check if the flood waters have receded, the bird takes to the blue skies and its plumage attains a beautiful blue tint. It also gets dangerously close to the sun and burns its breast a flaming orange. But when the kingfisher remembers the task, and returns, Noah has already left. Some believe that the kingfisher can still be seen hovering over the water in search of Noah.

Reincarnations of Gods

While some humans wish to be born with wings, ancient gods often took on the feathered form. A red and gold imaginary Bennu bird, (Bennu in Egyptian is purple heron), was born out of a sacred fire from a tree in the temple of the sun god Ra. The bird came to represent Ra’s soul, and the cycle of rebirth and regeneration, leading to its association with Osiris, the god of resurrection. It’s also believed to have inspired the legend of the immortal phoenix.

And “halcyon bird”, the Greek for kingfisher, can be traced to the love story of princess Alcyone and King Ceyx. When the couple casually refer to themselves as Zeus and Hera, Zeus is enraged. He kills Ceyx in a shipwreck, and grief-stricken Alcyone drowns herself in the sea. Touched by their love, the gods resurrect them as common kingfishers.