Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

My First Interaction

A quiet dawn unfolded over the winter forest. The morning mist hung lazily above the Ramganga. Elephants moved silently through long grass. Dead trees rose like sentinels. By the river, sambar deer grazed, gharials basked, and wagtails scurried over stones. Morning turned to noon and noon to dusk. In the fading light, a tiger crossed the dirt track, cutting through tall forests of sal. Almost a decade ago, just after my school exams in 2015, this was my first meeting with the forests of Jim Corbett National Park.

As a child, I had read about Jim Corbett’s hunting prowess. Later, I discovered his intimate relationship with India’s forests. But in 2025, on Corbett’s 150th birth anniversary, I tried to trace the story of the forest that carried his name. I found it in bits and pieces in the works of Rajeev Bhartari, D.C. Kala, Swati Sresth, and Brijendra Singh. In this article, I pull together pieces to create an account of the forgotten history of mainland Asia’s first national park.

The Advent of British Rule

Today, Jim Corbett National Park is spread over 520 sq km, while the larger tiger reserve spans nearly 1,300 sq km. But its boundaries and the concept of “Protected Areas” are based on the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972.

However, Hailey National Park was established much earlier in 1936. What legal ground did it stand on then? What rules governed it? And why was this forest chosen over all others in India?

To find these answers, we turn to the warring kingdoms of Kumaon and Garhwal. Around 1757, Najib Khan, a powerful chieftain from Rohilkhand, invaded Garhwal. Back then, the Doons — the Shivalik foothills — were thickly forested, and Najib Khan had used this to his advantage. To prevent future Rohilla raids, the Garhwal kings began clearing parts of these forests. When cultivation began in the jungles of Patlidun, along the Ramganga River, these lands came to be known as Dhikala after the Garhwali word, dhika (clods of moist soil that cling to the plough).

Over the next decades, Patlidun was governed by several rulers — Lalit Shah, Pradyumn Shah, the Nawab of Oudh, and then the Gorkhas. The British defeated the Gorkhas in 1814 and annexed Tehri–Garhwal. Most of the land was then restored to Garhwal’s Sudarshan Shah, who ceded the Patlidun forests to the British. In the dusty records of that land transfer lies the first official mention of Dhikala. Thus began the era of British rule over the forests of Patlidun — the land that would one day become Jim Corbett National Park.

Cover photo: A tiger in Jim Corbett National Park, India’s first national park (established in 1936) and the birthplace of the Project Tiger conservation programme. Photo: Shivang Mehta

Consolidation of British Rule

After defeating the Gorkhas in 1814, the British gradually took over all of present-day Uttarakhand. They cleared settlements like Dhikala to expand sal forests and source timber for building the railways and ships. Yet the name Dhikala persisted. Even in 1880, a British survey — “Working Plan of the Patlidun Hill Forests” — mentioned Dhikala and noted century-old remains of Rohilya and Gorkha settlements.

The region underwent major changes after 1800, when the British began building railways across India. In 1853, passenger trains ran for the first time between Bombay and Pune. Demand for timber skyrocketed. The Imperial Forest Department (1864) and the Indian Forest Act (1865) established strong colonial control over forests.

In Kumaon, Major Henry Ramsay relocated Buksa communities and banned farming and grazing in Patlidun. Ramnagar became a timber hub. By 1875, Nainital had emerged as the summer capital of the United Provinces. That same year, postmaster Christopher Corbett and his wife Mary Jane arrived in Nainital. Edward James (Jim) Corbett was born to them. Growing up in the forests of Nainital and Kaladhungi, he learned to fish, hunt, and read the jungle. In 1906, at 31, he hunted his first man-eater in Champawat.

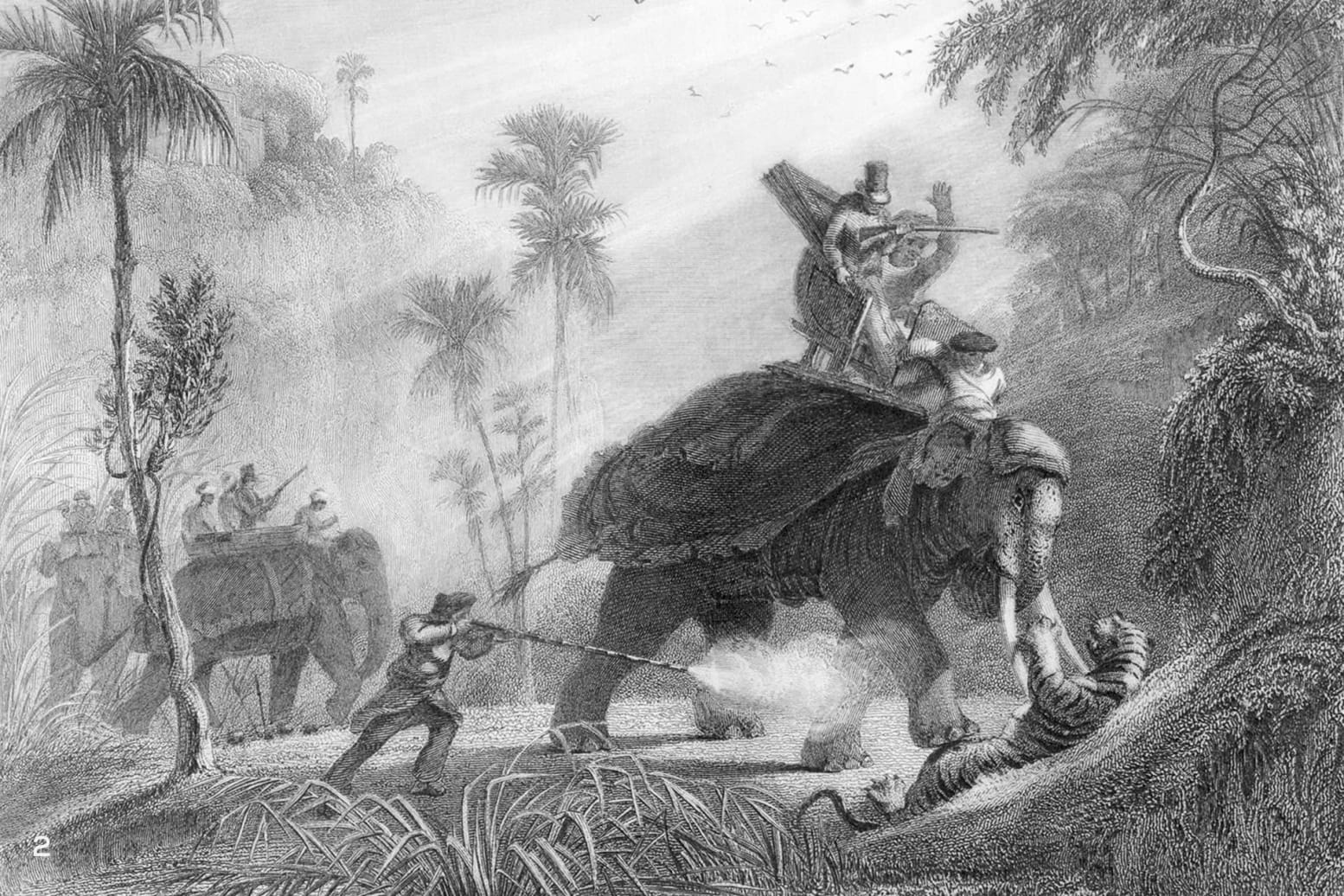

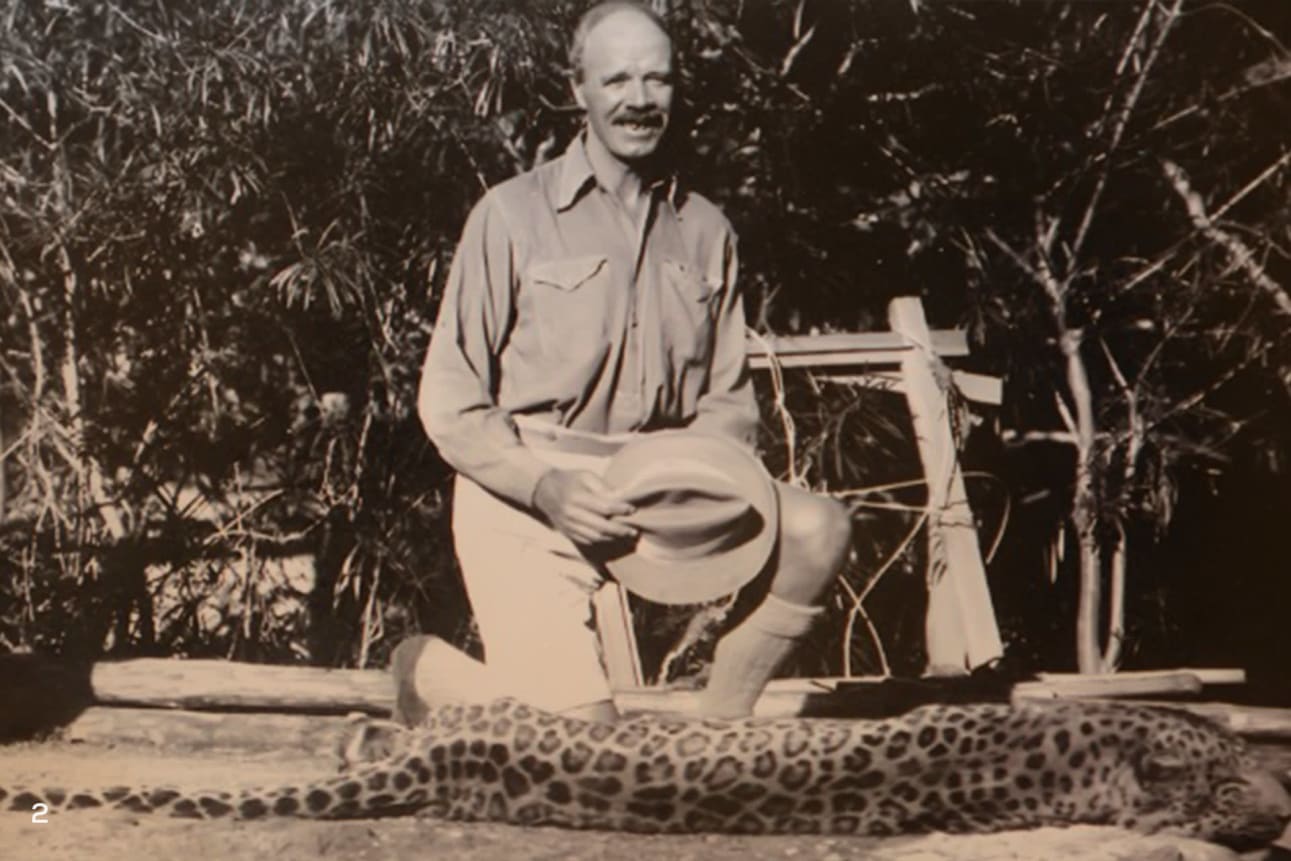

Tiger hunting was a popular sport for British officers. While Corbett is known to have hunted in moderation when necessary, he had also engaged in trophy hunting before giving up his gun for the camera.

Tigers were obstacles to development. The government incentivised these hunts. In 1911, when India’s capital moved to Delhi, the forests around Nainital came into focus. By 1918, the 1,500-sq-km Kalagarh Forest Division — including Patlidun and surrounding areas — was carved out. Along the Ramganga and Kosi rivers, over a dozen “shooting blocks” were set up. The lure of abundant game drew hundreds of British officers. Even with twenty bungalows, accommodating the hunting parties proved difficult.

The Political Context

In stark contrast to this ruthless hunting culture, America’s Yellowstone National Park had already inspired Protected Areas in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Europe by the turn of the 20th century. The British Government could no longer ignore this trend.

In 1912, the United Provinces passed the Wild Birds and Animals Protection Act. While the act protected small mammals and birds that were part of indigenous diets, it did little to curb British officers’ sport hunts. Between 1875 and 1925, around 80,000 tiger hunts were recorded. Still, with an estimated 40,000 wild tigers roaming India, administrators saw no real threat. Only Jim Corbett and a few others pushed for their protection.

In 1907, the Chief Secretary of the United Provinces submitted an official proposal for a Protected Area within Kalagarh Division, but Governor John Hewett rejected it. In 1916 and 1917, E.R. Stevens, the executive officer of the Ramnagar Forest Division, also submitted proposals restricting British officers’ hunting rights. However, Percy Wyndham, the Commissioner of Kumaon, refused to do so.

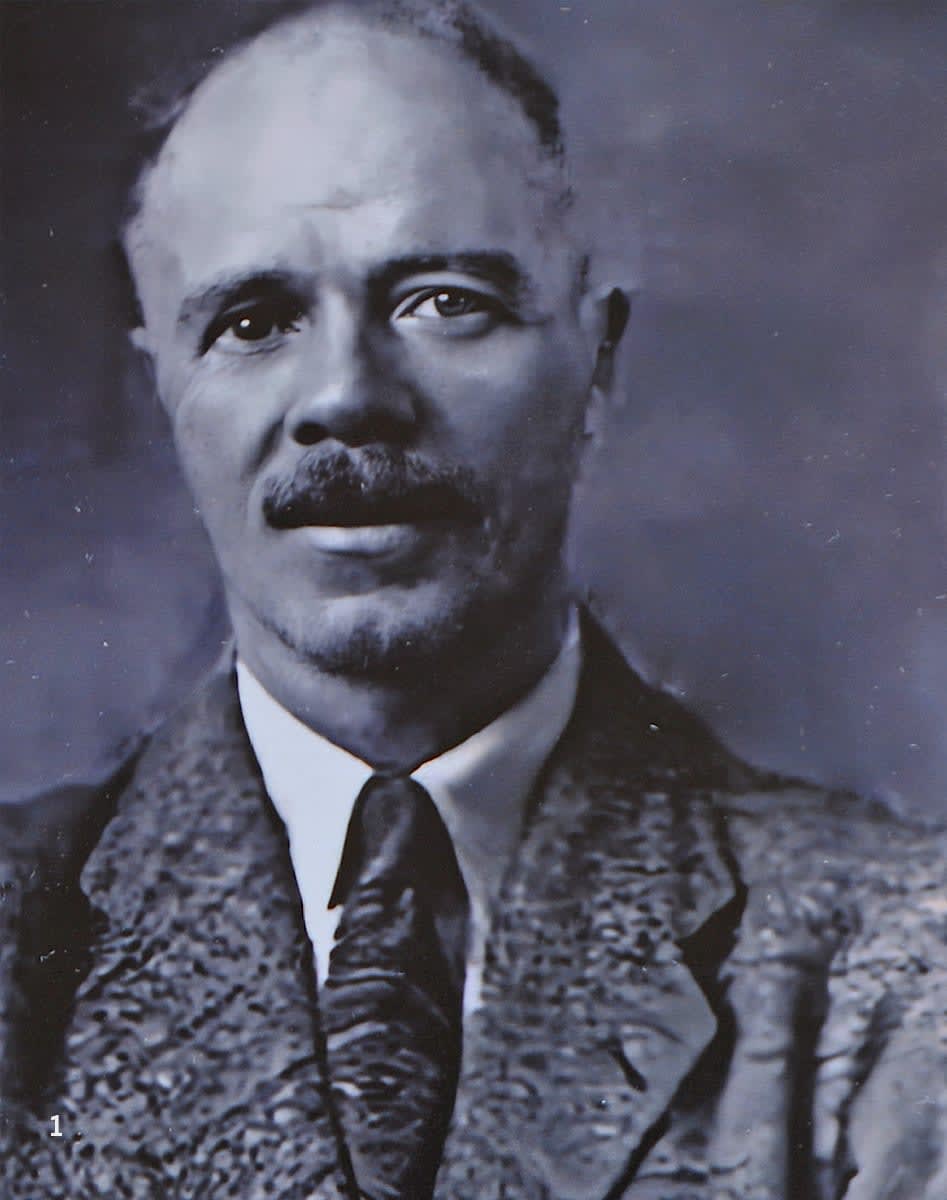

Corbett pressed on through his contacts, notably Sir William Malcolm Hailey. In 1928, when Hailey became Governor, Corbett lobbied with him for Protected Areas during fishing trips along the Ramganga. In 1931, during Hailey’s second run as Governor, Corbett helped form the Association for the Preservation of Game in the United Provinces. Hailey was the patron, and Hasan Abid Jafri served as secretary. The Society for the Preservation of Fauna in the Empire (SPFE) also extended its work from Africa to India, recommending the protection of forests to Viceroy Linlithgow. The turning point came in 1931. At the International Conference for Protection of Nature (Paris), British Prime Minister Ramsey MacDonald sent a message stating, “…United Kingdom regard themselves as trustees for the Protection of Nature.” A global definition of Protected Reserves followed in 1933 at the London Conference for the Protection of Flora and Fauna. Stuart Baker, representing British India at the Conference, was influenced by African conservation models and echoed Ramsey stating, “…it would be a wonderful thing for India to have such national parks in each province where wildlife could remain unmolested”.

The Colonial Government initially thought of setting up India’s first national park in Mudumalai. When local opposition blocked that move, Corbett and Governor Hailey pressed on for a Protected Area in Kalagarh. In 1934, with Corbett’s help, forest officer Arthur Smyth proposed initial boundaries and charted out a 500-sq-km Protected Area.

Hailey pushed further for a permanent legal framework, and the United Provinces National Park Act was drafted. But by the time it was passed in 1935, his term had ended. Governor Harry Haig redrew the boundaries, reducing the Protected Area to around 320 sq km. Honouring Hailey’s legacy, this Protected Area — the first in India and mainland Asia — was formally established as Hailey National Park on 8 August 1936. Rules were modelled on South Africa’s Kruger National Park. However, Dhikala’s grasslands and the Ramganga River were left outside the Protected Area. The riverbanks remained prime tiger-hunting grounds.

Wildlife observation gained popularity in the protected forests. Narrow sher batiyas (corridors) were cleared to enhance tiger sightings, elephant rides were brought in for tourists, and eight watchtowers were built. Hailey National Park gradually emerged as a centre for wildlife tourism while hunting remained rampant just outside it.

Independent India

After Indian independence, Hailey National Park was renamed Ramganga National Park in 1952. Ironically, the Ramganga riverbanks and Dhikala remained outside the park’s limits. After Corbett’s death in 1955, his longtime acquaintance Govind Ballabh Pant (first Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh in independent India) pushed to rename the park in Corbett’s honour. In 1956, the forests of Patlidun gained their present identity as Jim Corbett National Park.

Five years later, the Ramganga Hydroelectric Project created a 42-sq-km reservoir that submerged the Phulai and Buksar grasslands. Herbivore habitats and predator movements changed. Elephant migration corridors, linking Patlidun to today’s Rajaji National Park, disappeared forever. To compensate for this loss of forest land, 197 sq km of the park’s adjoining area was annexed to Jim Corbett National Park, defining today’s 520-sq-km expanse. Dhikala’s grasslands and the Ramganga riverbank were finally brought under protection.

WLPA 1972 and Tourism Boom

In November 1969, the IUCN Tenth General Assembly in Delhi highlighted the global threat to tigers, and WWF pledged financial support to India. Under PM Indira Gandhi, wildlife conservation efforts intensified. Tiger hunting was banned nationwide in 1970, and the Wildlife Protection Act came into force in 1972.

By 1973, the tiger was India’s national animal, and Project Tiger had kicked off. Jim Corbett National Park’s 520 sq km was designated a Tiger Reserve. With the core zone restricting access to the Paterpani, Jamunaghar, and Gajpani bungalows, the Dhikala Forest Resthouse gained prominence.

In 1985, the Dhikala Forest Bungalow hosted the 25th Working Session of the IUCN Commission on National Parks, attended by officials from 17 countries. A tourism boom followed. The park generated 8 lakh rupees (~70–80 lakh today) in revenue. But live baiting practices to ensure tiger sightings have increased human-wildlife conflict in adjoining villages. Following a child’s death in Laldhang, the 300-sq-km Sonanadi Wildlife Sanctuary and scattered Kalagarh forests were added as a buffer zone to the Tiger Reserve in 1991.

By 1991, Jim Corbett Tiger Reserve spanned 1,300 sq km. Starting with Bijrani, new tourism centres were developed across the park. Four relocated village sites — Dhara, Jhirna, Birna, Kothirau — formed the Jhirna Tourism Zone, while the forests of Mandal and Maydawan became the Durgadevi Zone. Revenue soared from 8 lakh rupees in 1986 to 88 lakh in 1997–98.

In 2000, Uttaranchal was carved out of Uttar Pradesh as India’s 27th state. About 30 sq km of Jim Corbett National Park’s forests remained under Uttar Pradesh, while 1,288 sq km came under the new state. This triggered a poaching surge, and eight adult tuskers were killed in late 2000.

By 2004, MP’s Sariska Tiger Reserve was tigerless, and national action followed. The 2006 WLPA amendment created the National Tiger Conservation Authority and Wildlife Crime Control Bureau. Due to relocation measures, scattered settlements in Kalagarh-Dhikala began to pose legal challenges.

Despite the confusion over relocation and forest-use rights, the tiger census showed steadily rising numbers. Tourism expanded. Following Dhikala, Sonanadi, Bijrani, Jhirna, and Durgadevi, Pakhro (2019), and Garjia (2020) Zones were opened to tourists. In 2022, Corbett recorded the highest tiger population in India.

In 2021–22, tourism revenue exceeded 10 crore rupees. Questions arose about how tourism wealth was concentrated in the hands of luxury resorts. The benefits to locals remained uncertain. But Jim Corbett National Park and Tiger Reserve undoubtedly secured its place as a landmark on national and global wildlife tourism maps.

Shaped by Exceptions

More than numbers and laws, the Jim Corbett National Park was shaped by exceptional individuals. From the park’s earliest days, local communities were recognised as partners. When Hailey National Park’s boundaries were drawn, Corbett ensured villagers’ rights were respected. We see this through programmes like the Canning Benevolent Fund, created to support families of forest staff who died on duty, instituted by an enterprising Forest Officer in the formative years of Hailey National Park. Rajiv Bhartari, former director of the Tiger Reserve, bears testimony of how this approach helped, “When Corbett National Park was formed, the initial boundary was very carefully determined so that no rights of villagers were affected. From its inception, it has enjoyed the goodwill of people because of Jim Corbett. I think that’s his legacy, the unique relationship between people and conservation.”

Long before his book Man-Eaters of Kumaon (1944), Corbett wrote in an article in 1932: “A country’s fauna is a sacred trust, and I appeal to you not to betray your trust…If we do not bestir ourselves now, it will be to our discredit that the fauna of our province was exterminated in our generation and under our very eyes, while we looked on and never raised a finger to prevent it.”

Corbett lived by this principle of going the whole distance to protect what he loved. Corbett never lived to see India’s first national park bear his name, and his first biographer Durga Charan Kala writes that such a development might have actually embarrassed him: “I am sure Corbett would have been embarrassed to take over the park once named after Malcolm Hailey….Corbett was dead when the renaming came. But what could be a more fitting memorial than a tract of forest in the Himalayan foothills for the tiger to survive in, hopefully forever?”