Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

It is not often you see birds on matchboxes. An art series called the Burning Birds of India is out to change that. Conceptualised by birder Mitul Patel and matchbox collector Asif Kureshi, it features 12 matchbox designs, each illustrating one endangered bird. In the fleeting nature of a burning match, the duo found a metaphor to the disappearance of our country’s, and planet’s, avian inhabitants.

There are 10,966 species of birds in the world with about 13 per cent on the brink of extinction. India has over 1,300 species of resident and migratory birds, of which 17 are critically endangered and 21 are endangered. To draw attention to these endangered species, Patel, who is art director at an advertisement agency in Mumbai, teamed up with Kureshi, a New Delhi-based independent graphic designer.

They first thought of producing a bird-themed calendar, which explains their choice of 12 species, but then they changed their medium to the humble matchbox. A matchbox is accessible to a wide range of people, says Kureshi, and people can interact with it every day.

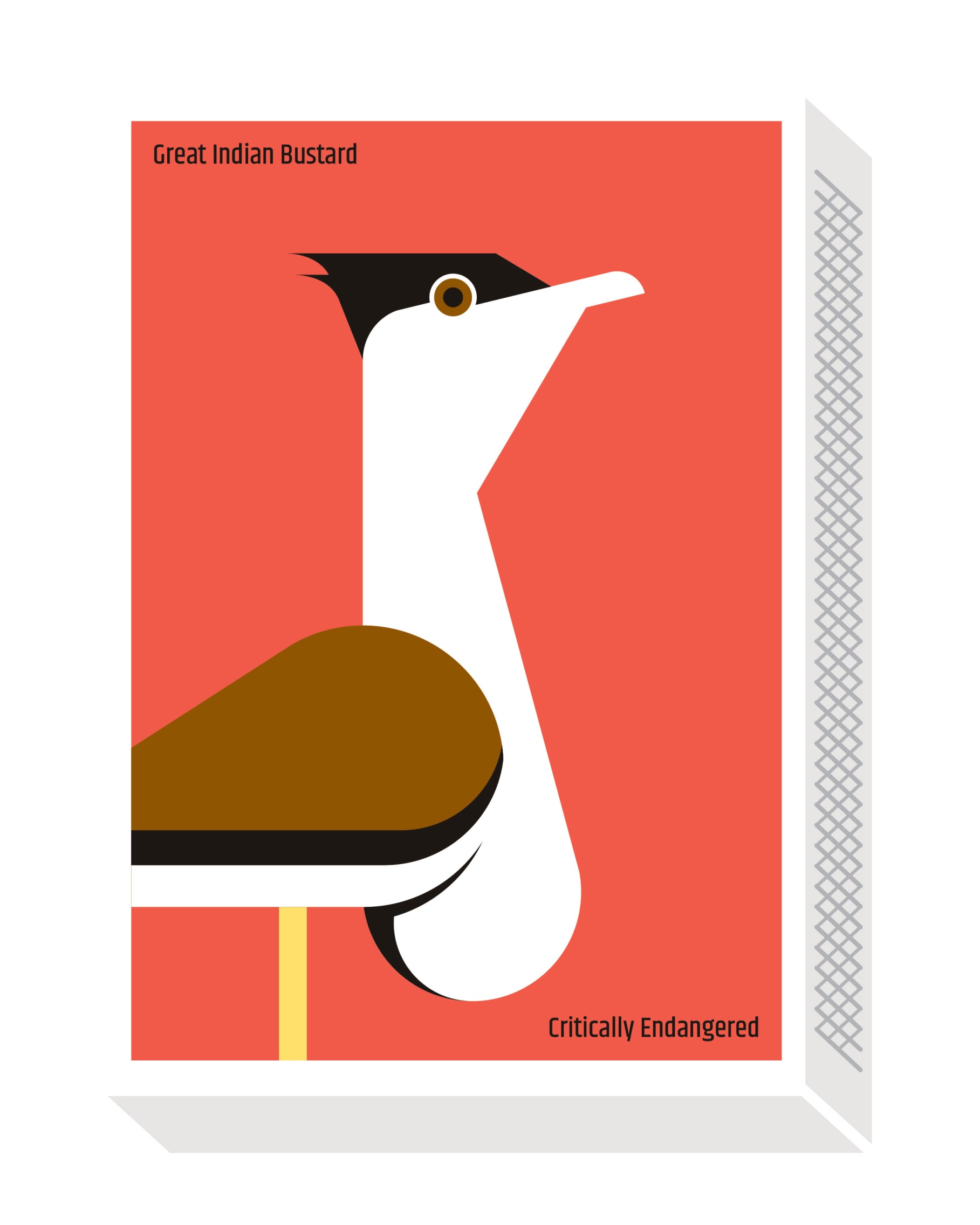

The 12 species featured in the project were picked from various groups, such as vultures, pheasants, bustards, and ducks, says Patel. Among these birds is the great Indian bustard, which is a step away from extinction in the wild. When Patel and Kureshi learned of Mumbai-based Sanctuary Asia magazine’s campaign to save the bustard, they donated their illustrations of the bird to the cause. Later, the two ended up collaborating with the magazine, which has since been sharing the illustrations on social media.

The illustrations are minimalist, and portray characteristics of a bird’s anatomy like eye stripes, wing patterns or shape and colour of the beak. Each illustration took Patel a few days to create, and he’d work on it between two and six hours every day. The artistic process involved sketching a species on paper, designing it in a software application, and adding the right colours.

With illustrations at the ready, Patel and Kureshi now face the challenge of mass-producing their unique matchboxes. To make a matchbox available at a low price, Kureshi says, orders have to be placed in the range of hundreds of thousands. While he looks for ways to fund factory production, he has made some mock-ups by buying blank matchboxes off the Internet and sticking printouts of the illustrations on them — the things artists do for the love of art.

The 12 Burning Birds of India

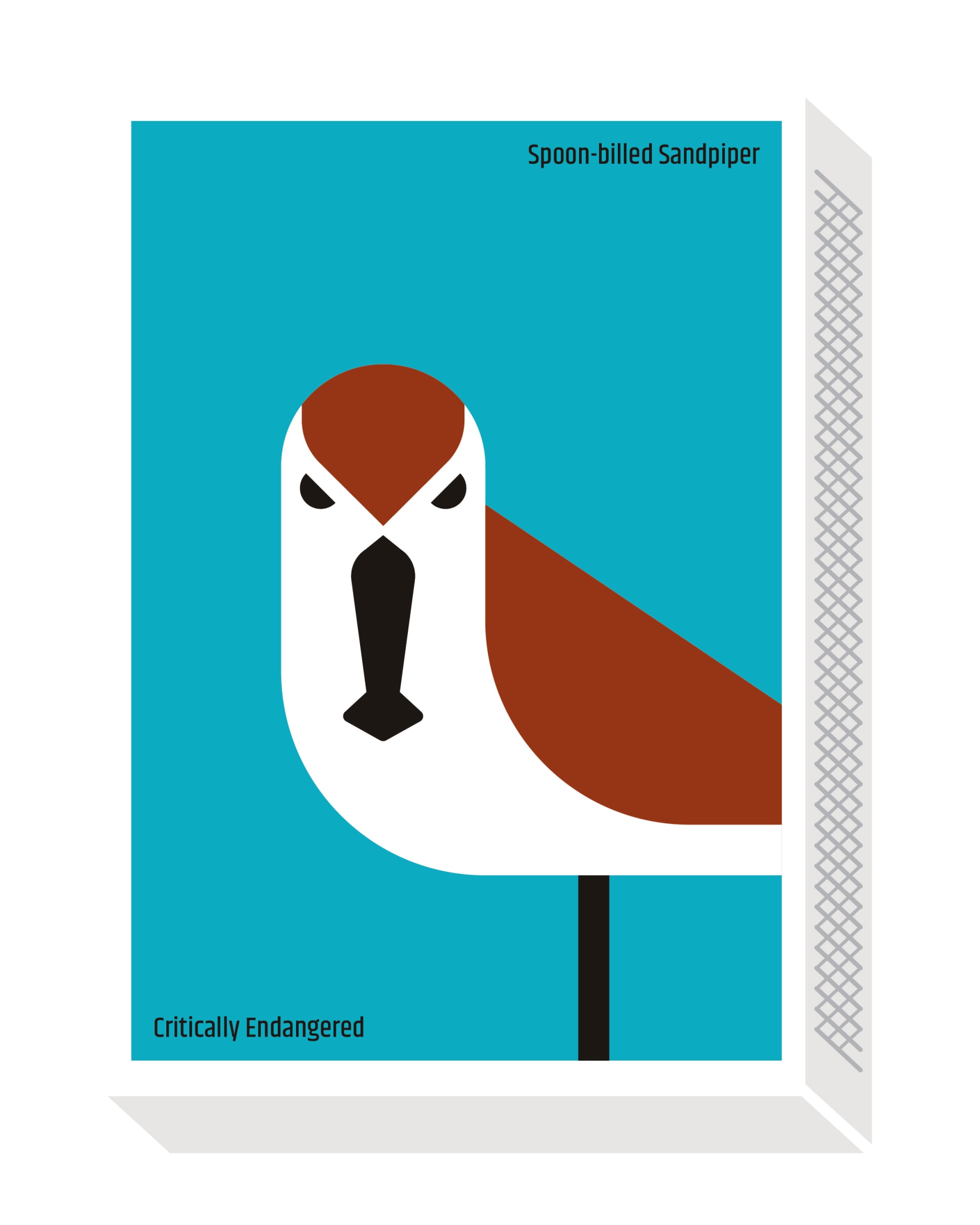

Spoon-billed sandpiper

Easily distinguished by its spatula-like beak, the spoon-billed sandpiper, ‘spoonie’ for short, is a migratory shorebird that breeds in Russia, and overwinters in China, Bangladesh, and Myanmar. Hunting and wetland reclamation are some of the threats to the tiny wader, which is a rare visitor to India — in 2018, it was seen for the first time in 70 years.

Himalayan quail

A species native to India, the Himalayan quail remains elusive; its last confirmed sighting was 143 years ago. Confusion prevails over its current status, as the IUCN Red List categorises the species as critically endangered, but according to field guides it is possibly extinct. If it still exists in its mountain home of Uttarakhand, its population is estimated to be around 50. Scientists predict that the species might go extinct by 2023.

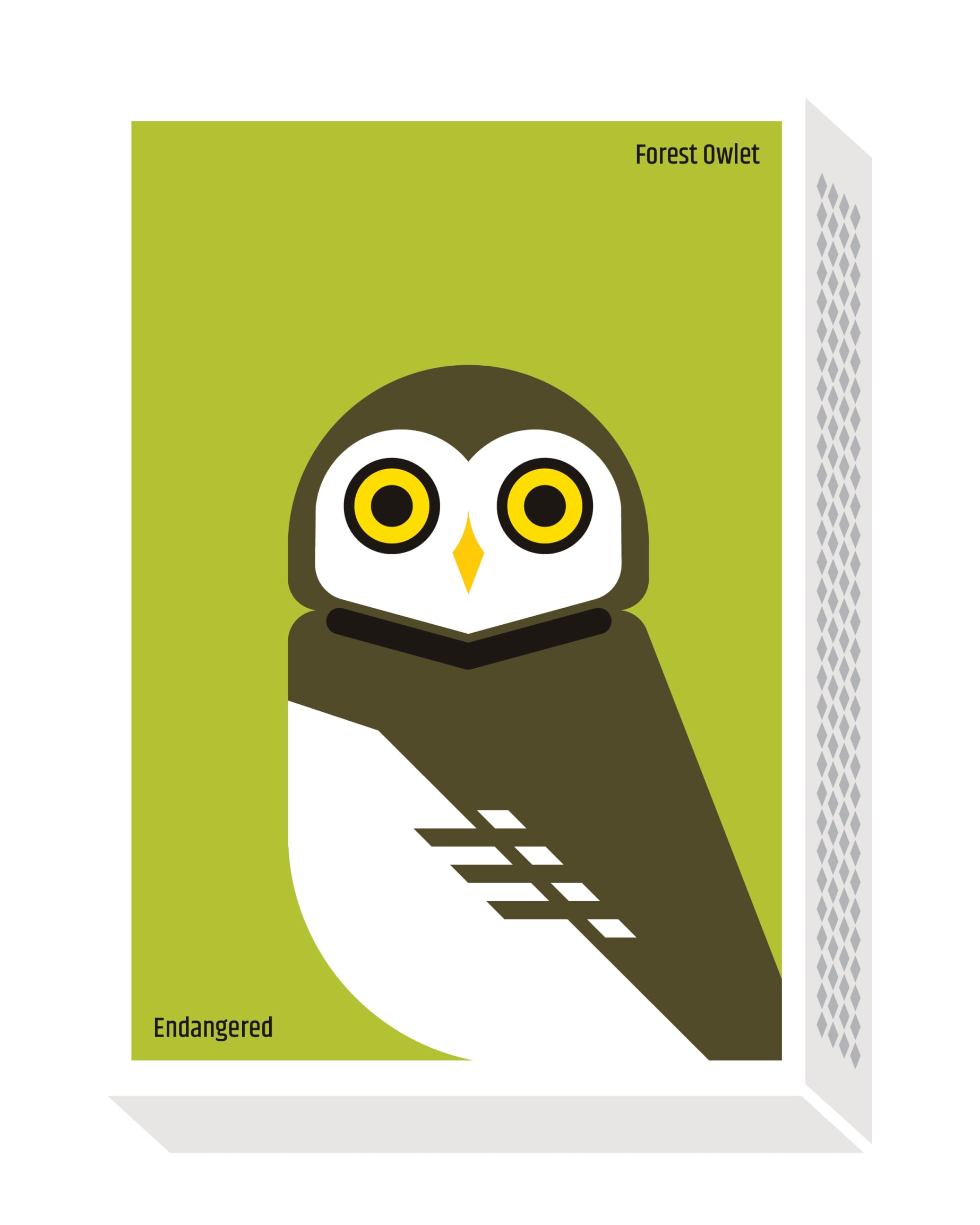

Forest owlet

Found in central Indian forests, the forest owlet is threatened by illegal tree felling, forest fires, and egg theft. In 2017, the species was down-listed from critically endangered to endangered, following the discovery of new populations, though lack of nesting trees remains a problem. Recent surveys have also revealed forest owlet hotspots in the states of Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat.

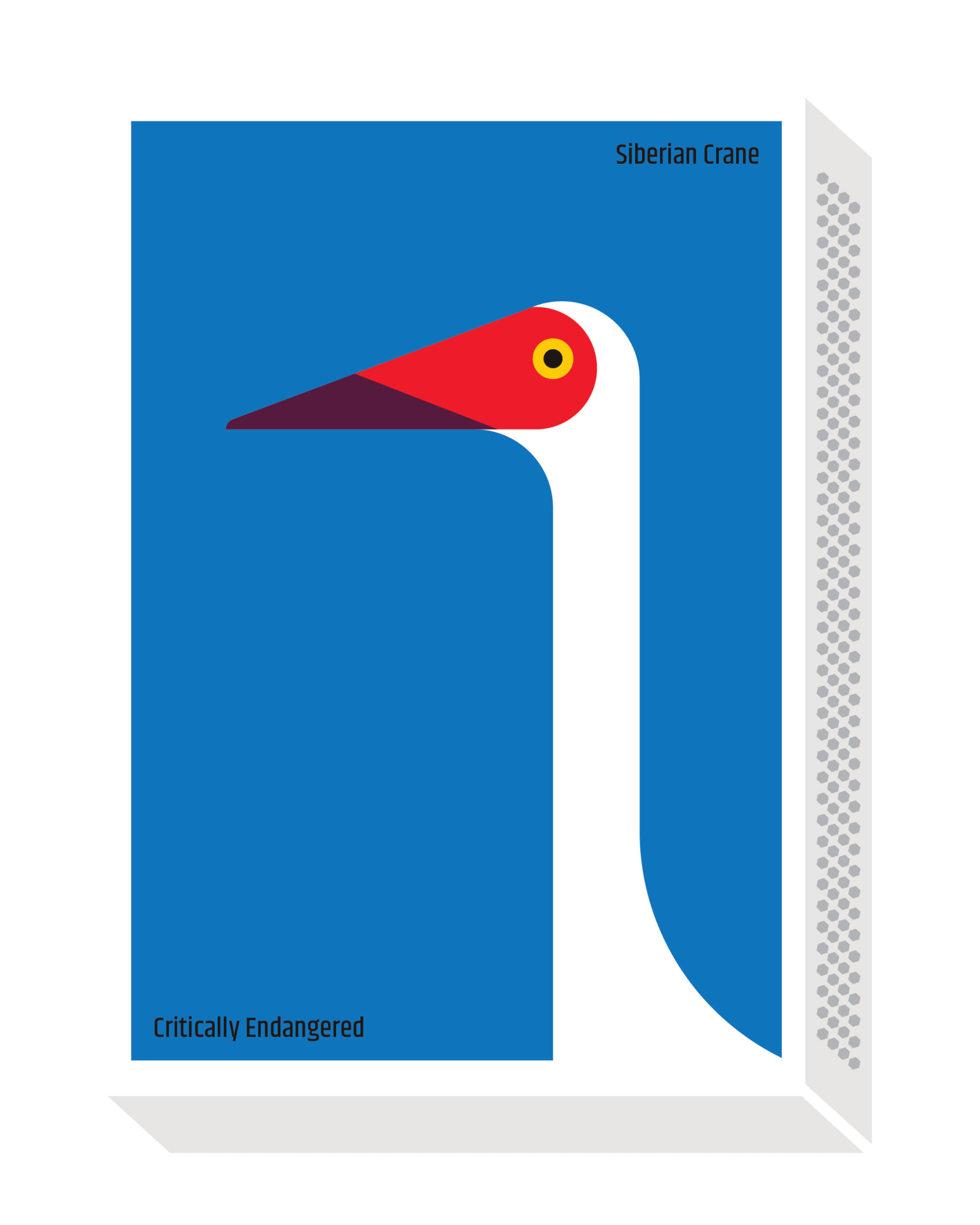

Siberian crane

With its snow-white feathers and deep red face, the Siberian crane has inspired art from back in the Mughal era. But as with many species that are beautiful, the Siberian crane too was persecuted, particularly along its migratory flyway. The snow crane, as it’s also called, would frequent India in the 1900s, to spend winters in Rajasthan’s Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary. But no birds have visited since the turn of the century.

Great Indian bustard

A grassland bird of the bustard family, the great Indian bustard is teetering on the edge of extinction. As a last resort to save the species, the Rajasthan forest department, the Wildlife Institute of India, and the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change have begun a bustard recovery programme. In 2019, eight eggs were collected from the wild and hatched successfully in captivity, according to wildlife biologist Sumit Dookia.

Bengal florican

Like other birds of the ill-fated bustard family, the Bengal florican numbers too are declining. The species breeds in grasslands and courtship involves males jumping into the air to impress choosy females. Scientists are now beginning to understand the species’ movement outside of the breeding season and finding that it spends time away from grasslands — in agricultural landscapes with small human populations.

Baer’s pochard

Restricted to Asia, the Baer’s pochard is a lesser-known and rare species of duck that has been declining due to wetland loss, and the hunting of eggs and adult birds. It is a winter migrant to India and, according to the eBird database, was seen at Kaziranga National Park in Assam as recently as January 2019.

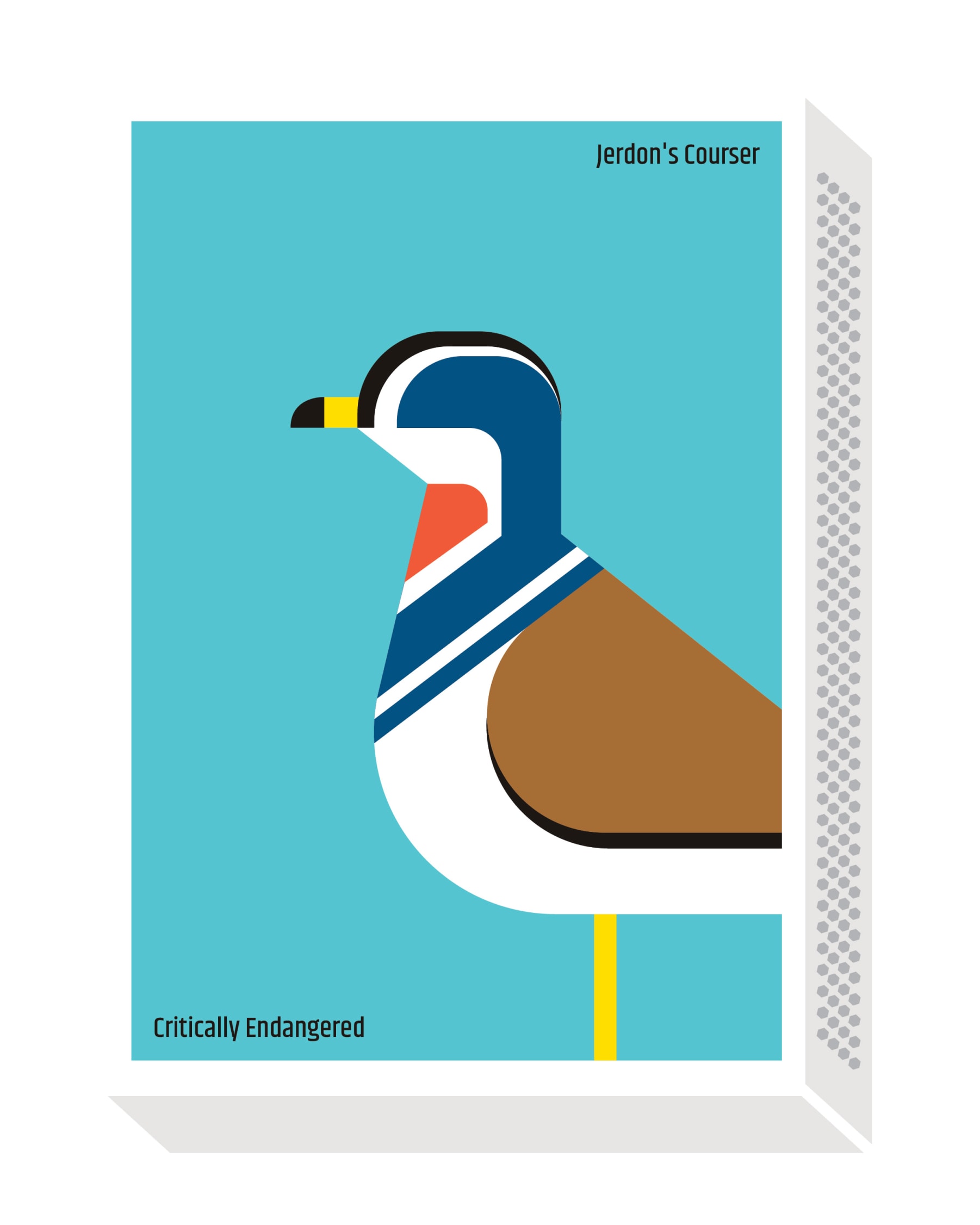

Jerdon’s courser

Endemic to India, the Jerdon’s courser is an inhabitant of the scrub jungles of Andhra Pradesh. This shy, nocturnal bird is so difficult to find that scientists have had to resort to studying its footprints on tracks made out of soil in potential and known habitats. The species is restricted to a few pockets, severely threatened by habitat loss, and hasn’t been seen in over a decade.

Sociable lapwing

Named for its behaviour of gathering in huge flocks before migrating from breeding grounds in Russia and Kazakhstan is the sociable lapwing, a bird of varied habitats such as grasslands, deserts, and wetlands. The species is illegally hunted for sport and food in the Mediterranean region, where some birds winter and others stop to refuel en route to their wintering grounds in Sudan, India, and Pakistan. The species is likely extinct through most of its range in northwest India.

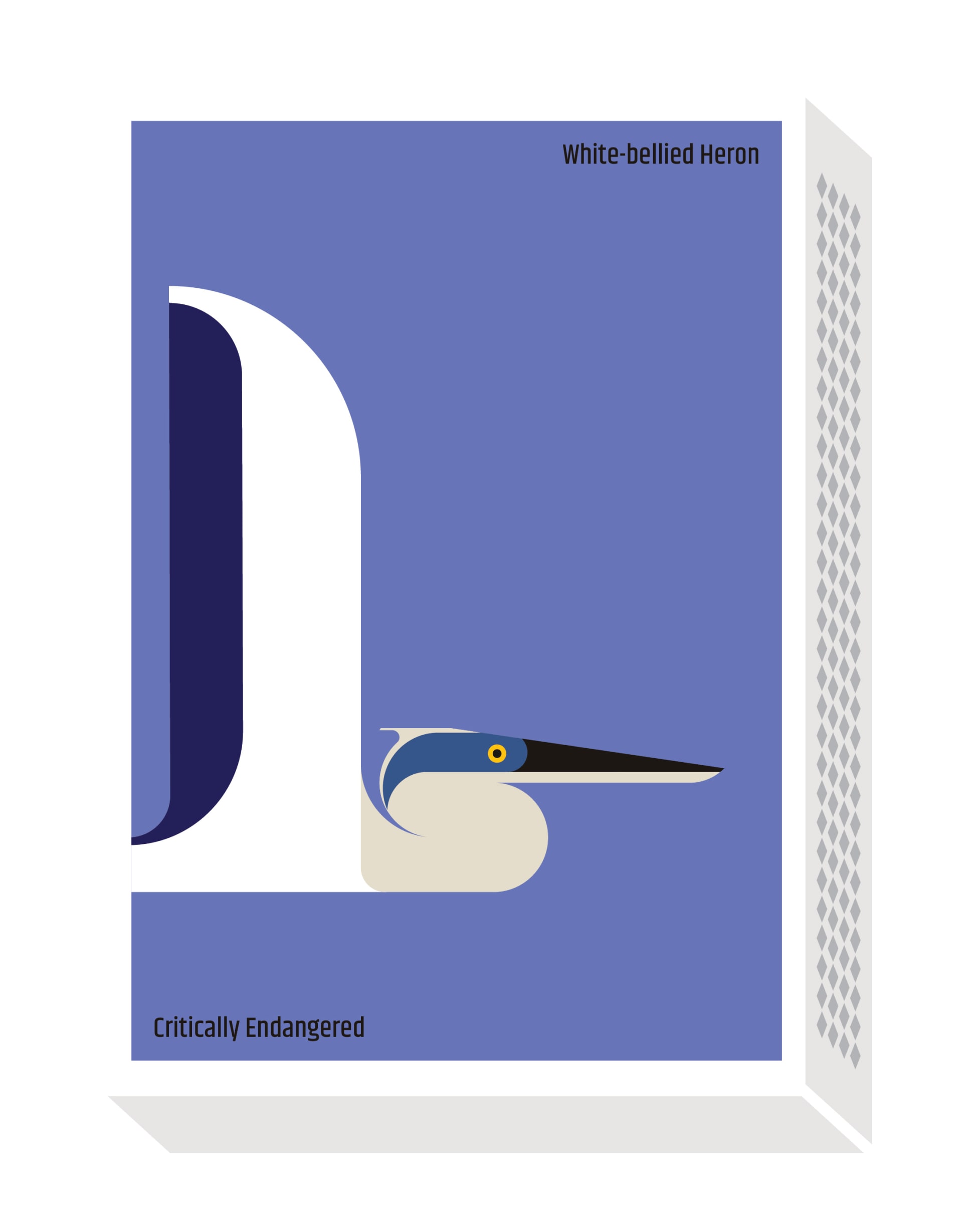

White-bellied heron

A slate grey bird with a white belly and wispy neck plumes, the white-bellied heron lives alongside water in the forests of India, Bhutan, and Myanmar. In India, it has been reported from Arunachal Pradesh, and occasionally from Assam. The species was first found breeding in India at Arunachal’s Namdapha Tiger Reserve in 2014. It is sensitive to human disturbance.

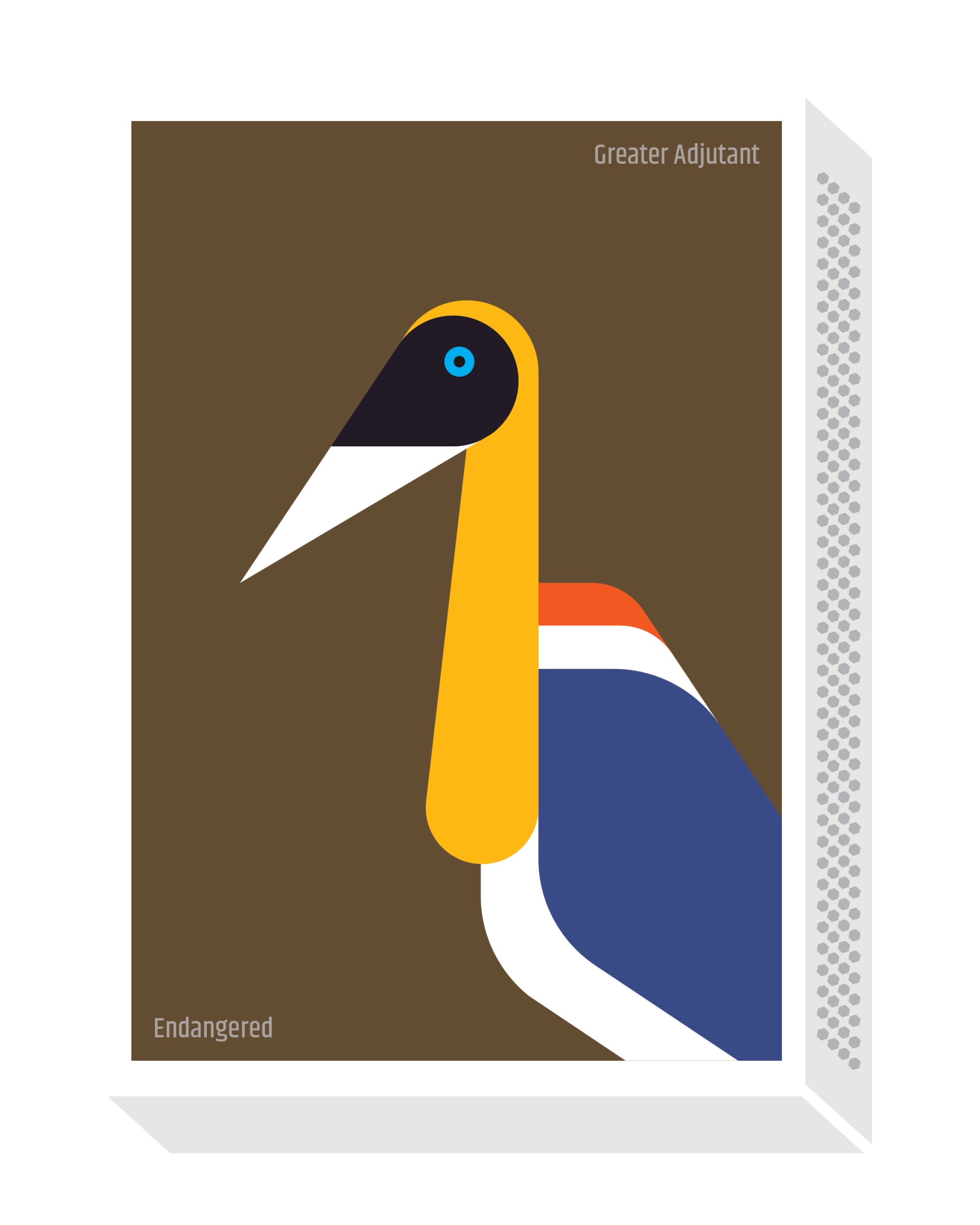

Greater adjutant

The greater adjutant used to be common in South and Southeast Asia, but now breeds only in India and Cambodia. In India, the states of Assam and Bihar host the last remaining populations of the stork. The species is slowly making a comeback thanks to conservation initiatives involving local communities. But it faces threats such as pollution in wetlands and contamination in landfills, where it scavenges for food.

Red-headed vulture

The red-headed vulture saw a steep population decline in the late 20th and early 21st centuries and is now missing from large swathes of its former range in South and Southeast Asia. One of many likely causes was toxicity from consuming carcasses contaminated with diclofenac, a drug that was found responsible for the downfall of other Asian vultures.