Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

I remember the night skies. Sleeping in the open under the stars. The clear brightness and the nearness of the stars. The warmth of the fire from an old driftwood log as we camped by the river.

I remember waking up feeling cold around 3 a.m., as the wood burnt out, and watching the dying embers. On several occasions, I singed my sleeping bag by being too close to the fire, getting holes in it.

I remember the forests – a crab-eating mongoose scurrying along on a forest path, turning once to look back and disappearing down a slope. I remember many other creatures seen momentarily. The rustling and movement in the undergrowth of dense bamboo, but, frustratingly, not revealing more of themselves.

I remember the forest sounds at night – the haunting call of the mountain scops owl, the chorus of the many unknown insects and frogs, the wail of a flying squirrel. The walks in pitch darkness, listening. We would switch off our torches just to feel the darkness. But soon, it would feel oppressive and scary.

I remember watching a red giant flying squirrel perched on a branch eating an unripe wild mango, and porcupines foraging on the forest floor below a fruiting fig tree. Once, with much excitement, we watched a small-toothed palm civet for a long time, our first and only encounter with the carnivorous mammal, also a first for those forests.

Another time, we came across the rare Hodgson’s frogmouth sitting in a bamboo thicket in the daytime, staring unblinkingly. Once an Asian grass lizard resting, half-submerged on a rock in a stream, a Draco hiding in plain sight on a tree bark as we finished recording data from a vegetation plot.

The magic of these forests is not only about spotting an animal – the glimpse of a startlingly coloured and rare root parasite while you are puffing your way up a steep climb is reward enough. There are the moss-covered branches, the snaking huge lianas, towering dipterocarp trees, the bright flashes of flowers amidst the green, the tree ferns that look like relics from the past, the coloured bracket fungi. The balsams, wild peppers, begonias and orchids – so much to stop for and marvel at. The sudden view of a thickly forested ravine from a steep hilltop.

Beyond the Assam plains with its fragmented forests, tea estates, oil wells, coal mines and the towns of Dibrugarh, Tinsukia, Digboi and Margherita, and past the Stillwell Road (aka the Ledo Road or Burma Road), as one approaches the hills of Arunachal, there lie some vast expanses of magical dense forest over 2,000 square kilometres, in the easternmost corner of India. They are surrounded by the snow-covered peaks of the Himalaya with the Dapha Bum as the highest point to the north and the lower lush forests of the Patkai hills to the east and south. This is a place of superlatives. It is among the last large tracts of wilderness in Asia, the last remaining lowland dipterocarp forests in north-east India, the world’s northernmost rainforests, contiguous with primary forests to the north, south and east in neighbouring Myanmar and the Yunnan province in south-west China, ranging from 100 to 4,500 metres in elevation.

Most of this forest is known as the Namdapha National Park and Tiger Reserve, spread over 1,985 square kilometres. It has everything from lowland rainforests, swamps, forest pools, lakes and river valleys to subtropical hill forests and temperate and alpine areas. Its biogeographic location and heavy rainfall add to the diversity – with over 1,000 plant species, over 100 species of mammals including at least fifteen that are globally threatened, 400-plus bird species, seventy-two reptiles and amphibians and much more, yet to be documented. Most of this area remains unexplored by outsiders due to the steep terrain, high rainfall and lack of roads or easily walkable trails. But even the limited surveys by biologists since the 1980s have yielded new records, new species and much knowledge. Beyond the boundaries of the tiger reserve, the forests continue – community forests in the Vijaynagar area, 637 square kilometres with several villages of the Lisu, a little-known tribe of Arunachal Pradesh (known officially as the Yobin tribe), and Nepali ex-servicemen. The latter were settled there by the Indian government in 1969, after the area was ‘discovered’ during an expedition led by a Major A.S. Guraya. They were settled there to safeguard the borders.

I remember the constant rushing sound of the formidable Noa Dihing river, which runs from the east to the west, later turning into the slower and wider Buri Dihing in Assam and eventually draining into the mighty Brahmaputra.

It felt comforting to listen to the river, while I was both snug and shivering in my sleeping bag. At other times, we would be camping by the cold, deep and swift snow-fed Namdapha river that flows from the Dapha Bum mountains and drains into the Noa Dihing at a place called Firmbase.

I remember on one of my winter visits to Namdapha and the Lisu villages beyond, we had managed to hitch a helicopter ride back from Vijaynagar (beyond Namdapha’s eastern borders) to Miao in Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh. I watched in awe the vastness of Namdapha’s forests – my eyes were moist taking in the mystery and beauty of the landscape. I was trying to spot the places I knew. I could even make out some Tokko (Livistona jenkinsiana) palm groves. And suddenly, a flock of ten wreathed hornbills, flapping hard and flying over the canopy, appeared right below us. My heart was full at the beauty of that unforgettable moment. It was a moment to treasure for a lifetime.

Those days and nights spent in Namdapha’s forests for almost nine years since 2003 are etched in my memory. The connection I have with the place is a visceral one. What makes Namdapha so magical and sets it apart from many other wild places is the feeling of being truly in the wild, far away, unconnected to civilization.

Yet it is not a wilderness that is devoid of people, and never has been, contrary to the dominant narrative. It took me time to realize that.

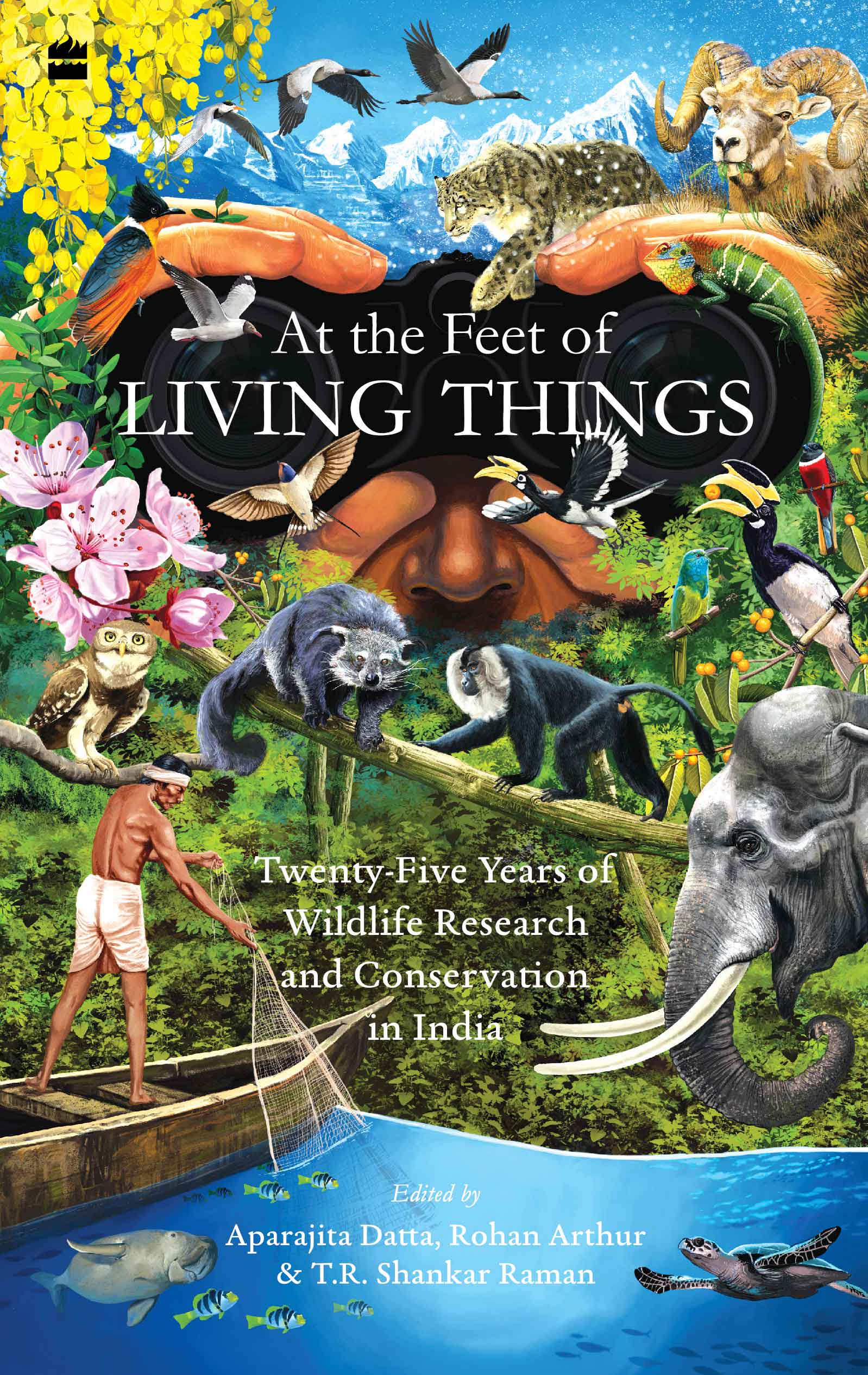

Excerpted with permission from ‘At the Feet of Living Things: Twenty-Five Years of Wildlife Research and Conservation in India', edited by Aparajita Datta, Rohan Arthur, T.R. Shankar Raman’, published by Harper Collins (Price Rs 599).

This edited extract is part of a collection of essays by scientists from the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF)