Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Story 1: In love with Lakshadweep

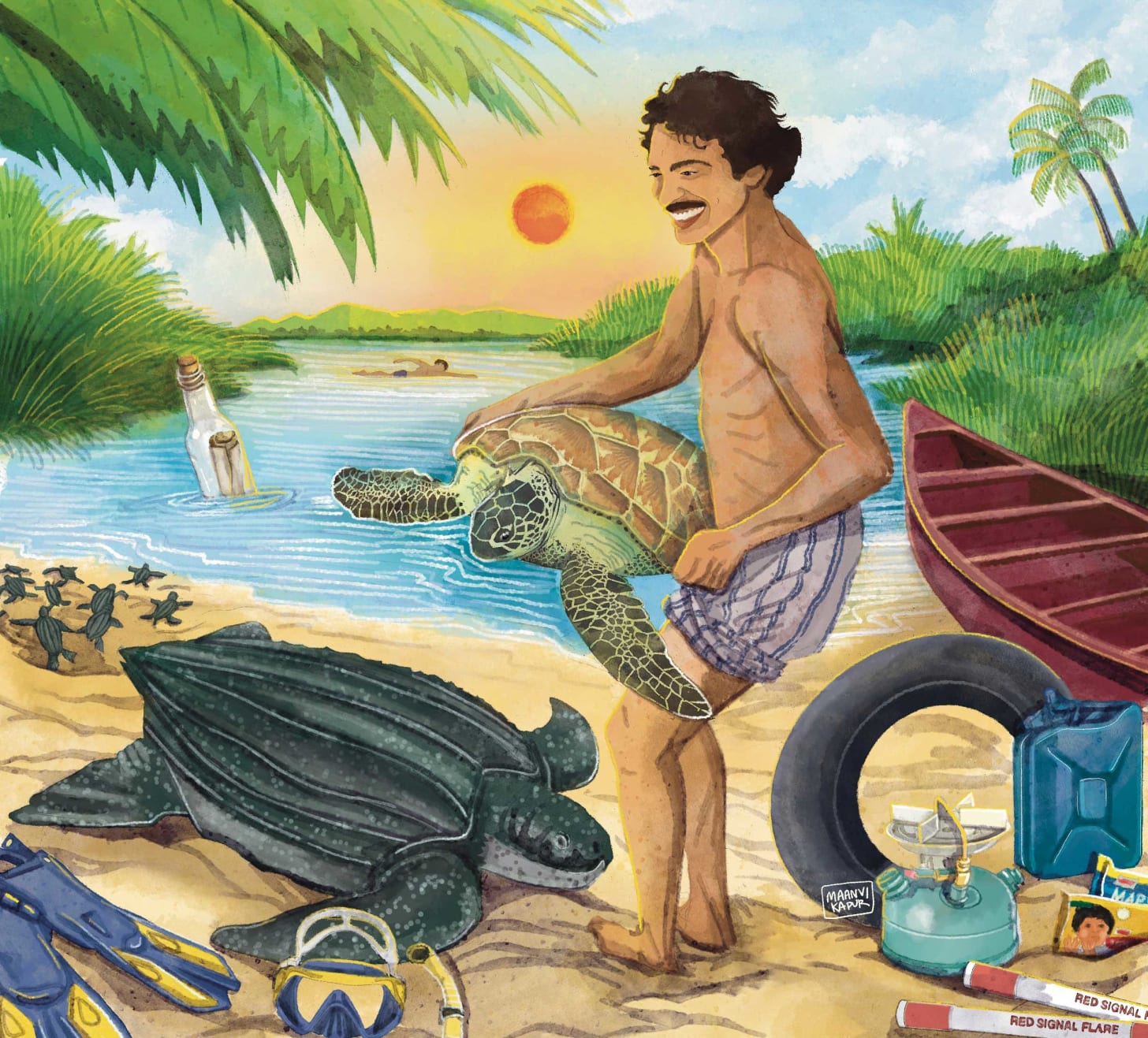

After a long unproductive stint at IIT Madras in pursuit of an Engineering degree, a period spent mostly swimming in the Bay of Bengal, Satish Bhaskar joined the Madras Snake Park and discovered a love for sea turtles. Following a visit to the Gulf of Mannar in 1977, Satish set off for the Lakshadweep and spent a few months visiting multiple islands in the group. He wrote of swimming with turtles in Minicoy and with sharks in Kavaratti.

Part of the Chagos-Laccadive ridge, the Lakshadweep are the northernmost islands in this series of coral atolls which also includes the Maldives. The Lakshadweep group consists of about 35 islands, of which 10 are inhabited. The larger islands are about 10 km long and not particularly wide and have large lagoons, typically on the Western side.

The lagoons are shallow and covered with seagrass meadows which provide a rich foraging ground for green turtles. Satish reported seeing green and hawksbill turtles more frequently in Minicoy than in the other lagoons. Whether these were natural abundances or caused by hunting of turtles in the other islands is not known.

Satish also found that the Suheli Islands, Valiyakara the big one, and Cheriyakara the small one, hosted the most green turtle nesting across the islands. But these were uninhabited islands, visited by fishers periodically during winter and never during the monsoon. But that’s when green turtles nested, and so this led to one of the most daring wildlife adventures of the time.

Story 2: Marooned in the monsoon

Satish and his co-conspirators at the Madras Crocodile Bank, Rom (Whitaker) and Zai Whitaker, started hatching a plan for him to spend the entire monsoon on Suheli Island. This involved getting dropped off there in May and spending 5 months there entirely on his own. There would be no companions and no visitors. And no contact with the rest of the world.

They planned for food supplies and water and medicines – for toothaches, infections, fevers and anything else they could think of; how do you pack for a place where there’s nothing but sand and sea? The Navy gave Satish some distress flares but it’s not clear who would have seen them as the Suheli islands are about 50 km from Kavaratti, and 6 to 8 hours by fishing boat.

Satish Bhaskar is a pioneer of sea turtle biology and conservation in India, best known for conducting one of the first systematic sea turtle surveys in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Illustration: Maanvi Kapur

Satish was dropped off in May and spent the next few months monitoring green turtles. During the day, he watched sharks swim around in the shallows feeding on a dead whale shark that had washed ashore.

By September, Satish had had quite enough. He was ready to leave but the weather was inclement and the boat could not make the journey from Kavaratti. They finally arrived nearly a month – yes, a month – late to pick him up.

Story 2: Sea mail at your service

One of the most iconic stories in the history of sea turtle conservation in India is the letter Satish’s wife, Brenda, received from him during his time at Suheli. Long before cell phone and satellite phones and email, it was remarkable that he managed to message her at all! It only took about a month.

With little else to do during the day, Satish decided to experiment with the old message in a bottle scheme. He would write a letter to his wife, stick in one of the bottles that had washed ashore, add a little money as incentive and throw it into the water. Of course, he couldn’t just throw it in the lagoon as it would float around the island for all eternity. So he’d wade out as far as he could towards the reef that surrounded the island and try and throw it into the open sea through a small channel. Soon he was running out of smaller notes and did not want to spend all his money. He started getting more innovative and tying the bottle to floats, including one time to a large Styrofoam sheet that he had found on the beach. Satish remembers the raft performing cartwheels with its precious passenger and spinning out to sea.

Who knows which bottle successfully escaped into the open ocean, but one finally did, and caught a current southward. Some days later, it rounded the southern tip of India like an intrepid medieval trader, and washed up on a beach in Sri Lanka. A journey of 800 km in 27 days, perhaps a bit longer than green turtles took to go back and forth along the same route.

To help complete its journey, a local fisherman, Anthony Damacious, found the bottle and kindly put the letter in an envelope along with a picture of his family and sent it to Brenda.

Story 4: A rising tide of turtles

Satish had noticed a larger number of green turtles in some lagoons than in others, but nothing particularly remarkable. By the mid 2000s, however, they were a regular sight in Kavaratti and Agatti. Basudev Tripathy, who in 2001 conducted the first surveys of the islands after Satish Bhaskar, noted high numbers in Agatti. By 2008, these numbers shot up to nearly 300 turtles per km2 but shortly after that, the numbers declined, and peaked again in 2013 and 2016. Green turtle abundances fluctuated in a similar fashion in Kadmat and Kalpeni where research organisations had started to monitor them.

Seven species of sea turtles swim our oceans. These large, air-breathing reptiles inhabit tropical and subtropical seas across the world. Illustration: Barkha Lohia

In the mid-2000s, Rohan Arthur and his team from the Nature Conservation Foundation started studying the impacts of turtles on seagrass species’ composition and characteristics (such as height and cover). A few years later, Dakshin Foundation researchers initiated monitoring of green turtles and seagrass to follow their abundance over time on different islands.

These studies now show that the turtles decimate the meadows in each of these lagoons, grazing them down to their roots. Once the seagrass resources are depleted in a lagoon, they seem to move on to another lagoon, and return when the seagrasses have recovered. But over the last two decades, the turtle numbers appear to have increased and the seagrass has little time to recover. This increase may be linked to the decline in natural predators such as sharks or even to conservation programmes in places like Gujarat and Sri Lanka. A turtle tagged in Sri Lanka was sighted in a Lakshadweep lagoon, and another one fitted with a satellite transmitter was tracked to the region.

Story 5: Conservation meets conflict

Increasing green turtle populations in the Lakshadweep lagoons have many downstream effects. Their intense foraging of seagrass meadows leads to the loss of habitat for many lagoon dwelling fish, including juveniles of many species. In particular, this affects the abundance of baitfish that local communities use for tuna fishing, their main occupation and source of income. Thus, fishers in many lagoons have begun to resent green turtles.

So it is entirely possible that conservation efforts in one place have ecosystems effects in another. The increase in green turtles in these islands has impacted both seagrass meadows and associated fauna, and result in conflict with local communities. Around the world, green turtle populations have increased dramatically in many sites leading some biologists to consider them as ‘threats’ to these ecosystems and even, in jest, as pests.

What happens when the seagrasses decline to a point where they can no longer sustain these populations? Will the turtles change their diet to feed more on algae, or will they move further afield to seek greener pastures? How will they know where to look? Only time and research will tell.

Excerpted with permission from the authors. Published by Dakshin Foundation. The book can be purchased here.