Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

A quiet, peaceful day in the Chug Valley of Arunachal Pradesh was disrupted by the desperate shrieks of a black-necked crane (Grus nigricollis). Dr Anurag Vishwakarma instinctively guessed what might have transpired. Indeed, as he assumed, free-ranging dogs had attacked a pair of black-necked cranes, and the male had suffered injuries to its right wing, rendering it unable to fly.

Dr Anurag, who has been working as a researcher, immediately posted a picture of the injured crane on social media, seeking help. A coordinated rescue effort was led by Mr Obang Tayeng, the Divisional Forest Officer from Bomdila. The team was joined by Dr Darge Tsering (senior veterinarian officer), Omar Ahmed (researcher from the Wildlife Institute of India), Dr Panjit Basumatary (veterinarian from Wildlife Trust of India’s Centre for Bear Rehabilitation and Conservation) and the local community.

When strays go wild

India is home to the fourth-largest population of free-ranging or stray dogs — 35 million — supported by a booming human population. What makes it even more complicated is our natural attachment to these four-legged companions, who have been selectively bred through centuries to meet our needs. But somewhere down the line, we abandoned these very companions, who then instinctively return to hunting and scavenging, but are still attached to human proximity — growing in pack size and spreading.

These dogs are highly dependent on human-provided food, though being a subspecies of the wolf, their inherent hunting instinct is also present. In and around rural areas and Protected Areas, where wildlife populations are higher, domestic stray dogs have ample opportunities to hunt and interact with wildlife at multiple levels, disrupting nature’s food chain.

A study by Vanak and Home in 2017, published in Animal Conservation, highlights the direct killing of more than 80 species of wildlife by free-ranging dogs. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Studies have also documented inbreeding and hybridisation between free-ranging dogs and wolves or golden jackals in India, posing a serious threat to the wild populations of these species. Free-ranging dogs are also a reservoir of diseases which can and have impacted the wildlife in their vicinity. A similar study published in Biological Conservation reports that 11 vertebrate species went extinct and 188 threatened species are at risk from free-ranging dogs.

When conservation finds many hands

Injured and understandably wary of humans, the injured male crane was in distress, but the rescue operation finally succeeded. The bird showed signs of acute exhaustion and dehydration and was placed in a temporary rehabilitation centre in Chug Valley. Under the supervision of Dr Darge, the crane was closely monitored, and a diet rich in grains and aquatic vertebrates provided.

In the next few weeks, the seasons shifted, and the region warmed up. The female, who was still sighted nearby, joined the cranes’ annual migration. A collective effort was made to translocate the injured male to Morshing, a cooler valley away from human chaos and better tuned to its natural needs. The relocation site was carefully selected based on this species’ habitat preferences. Under the watchful eye of Dr D K Thungon, Veterinary Officer and his team in Morshing, every effort was made to help the crane recover — with the hope that it may rejoin its mate.

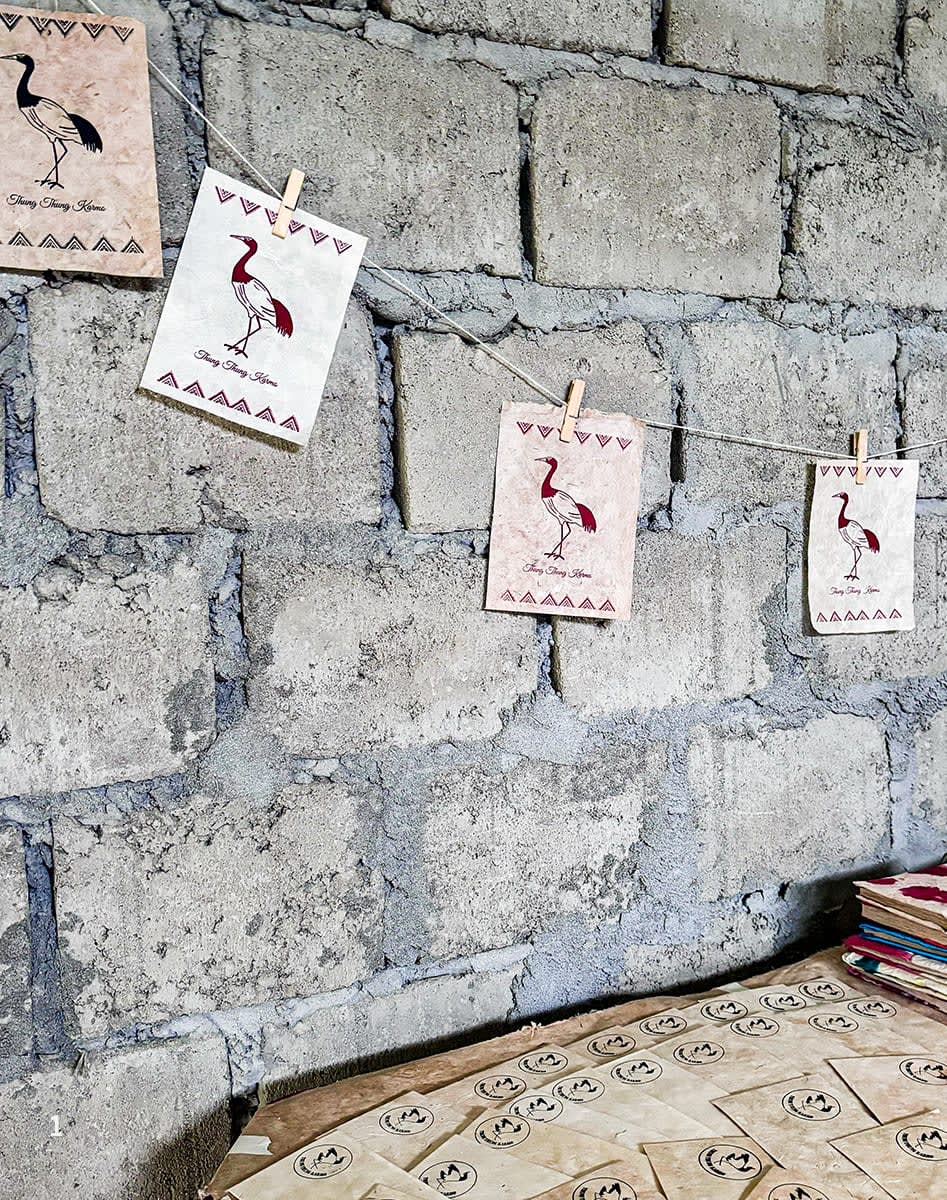

Wildlife Trust of India’s (WTI) Rapid Action Project (RAP) has been supporting urgent, small-scale conservation needs such as these since 1999. Since 2023, the RAP grant has helped Tripti Shukla, an independent researcher and co-founder of Vanwasi Aadiwasi Foundation, revive the dying, century-old tradition of making handmade paper from the inner bark of the shugu-sheng plant. Through this effort, she is also fostering conservation awareness about the black-necked crane in the Chug and Sangti Valleys by conducting workshops that link the traditional craft to crane conservation. Altogether, it’s a win-win situation for both the community and conservation efforts.

This crane attack was not the first incident. Similar attacks by free-ranging dogs on black-necked cranes have been recorded in Ladakh. A similar incident was also reported by WTI’s project team in Central India, when a spotted deer was attacked by a pack of free-ranging dogs. In fact, there are hundreds of cases of free-ranging stray dogs killing wildlife in India.

Wings that disappeared from Seinthuk village

Locally known as “thung thung karmu” the black-necked crane is classified as “Near Threatened” on the IUCN Red List. According to the International Crane Foundation (ICF) website, the black-necked crane population is estimated at around 16,500 individuals and is increasing (mature and immature individuals). In Sherdukpen culture, it is respected, and its migration is believed to bring prosperity to the village.

Black-necked cranes mate for life and will normally remain together till one dies. For the Monpa community, the thung thung karmu is not just a bird — it’s a deeply rooted emotion. These birds are believed to be connected to the incarnation of the sixth Dalai Lama; their arrival is believed to bring good luck and a bountiful harvest. Among Buddhist communities like the Monpa, hunting this revered bird is strictly forbidden.

“Thung thung karmu is a Mother God for us, a sign for peace and prosperity. Earlier, it used to visit our village regularly, but our greed, expanding our agricultural lands and real estate, has slowly destroyed its habitat”, says Dorjee Khandu Khrimey, WTI field attendant and a resident of Seinthuk (Shergaon).

The local folklore speaks of a family — a father, Aapu, and his three sons: Blechung Khaw, the eldest; Thepogali, the middle son; and Blenchung Chan, the youngest. When a dispute split the family, Thepogali was left with nothing. Alone and adrift, he wandered through forests and ridges until he was lost in a cave where a sacred nest of a black-necked crane was present. From the three eggs in that nest emerged the cosmology of an entire people: a white yak that soared to the heavens, a red yak that plunged into the underworld, and a black yak that remained on earth. Upon this earthly yak sat Pandan Lamu — the guardian deity still worshipped by the Sherdukpen community. The nest, the crane, and the deity became inseparable — a divine origin rooted in the highland bird’s sacred shelter.

Today, the black-necked crane no longer nests in Seinthuk. What was once a bearer of the gods is now remembered only in myths. The sacred nest that once bridged the heavens, underworld, and earth has been reduced to memory. But the reverence continues. Pandan Lamu is still honoured. The crane is still sacred. This lingering cultural memory is not just a relic; it is a reminder. To honour the deity is to remember the bird. And to remember the bird is to ask: can it ever return?

Sightings of black-necked cranes have become rare in places that used to be their wintering grounds in these valleys. Along with the growing human population and interference, the population of free-ranging dogs around these crucial wildlife habitats grew.

We have all been awed by moments when a tiger chases a deer, when a pack of dhole brings down a sambar, or a small cat hunts a rodent. These visuals have been the heartbeat of wildlife storytelling. But things get awkward, even disturbing, when it is a “stray” or “free-ranging” dog hunting down the same wildlife. Man’s best friend, they say. But we know this bond was never natural; it was shaped by us. Incidents of free-ranging dogs attacking wildlife have gradually become the norm. Be it nilgai in Northern India or the great Indian bustard in Rajasthan, Pallas’s cats and snow leopards, smooth-coated otters and olive ridley turtles — many species, across India’s wild landscapes, have been affected.

To conclude, I leave this question open for the readers: Are we failing to protect our wildlife from our canine companions? Is it we who have brought this upon wildlife? Until then, I hold onto the hope that the injured crane will be able to fly again and find his way back to his home and mate, in a peaceful valley.