Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

The Kole wetland in Kerala is popular for its paddy cultivation that dates back to 300 years. The wetland gets its name from its high productivity – ‘Kole’ literally translates to ‘bumper crop’ in Malayalam.

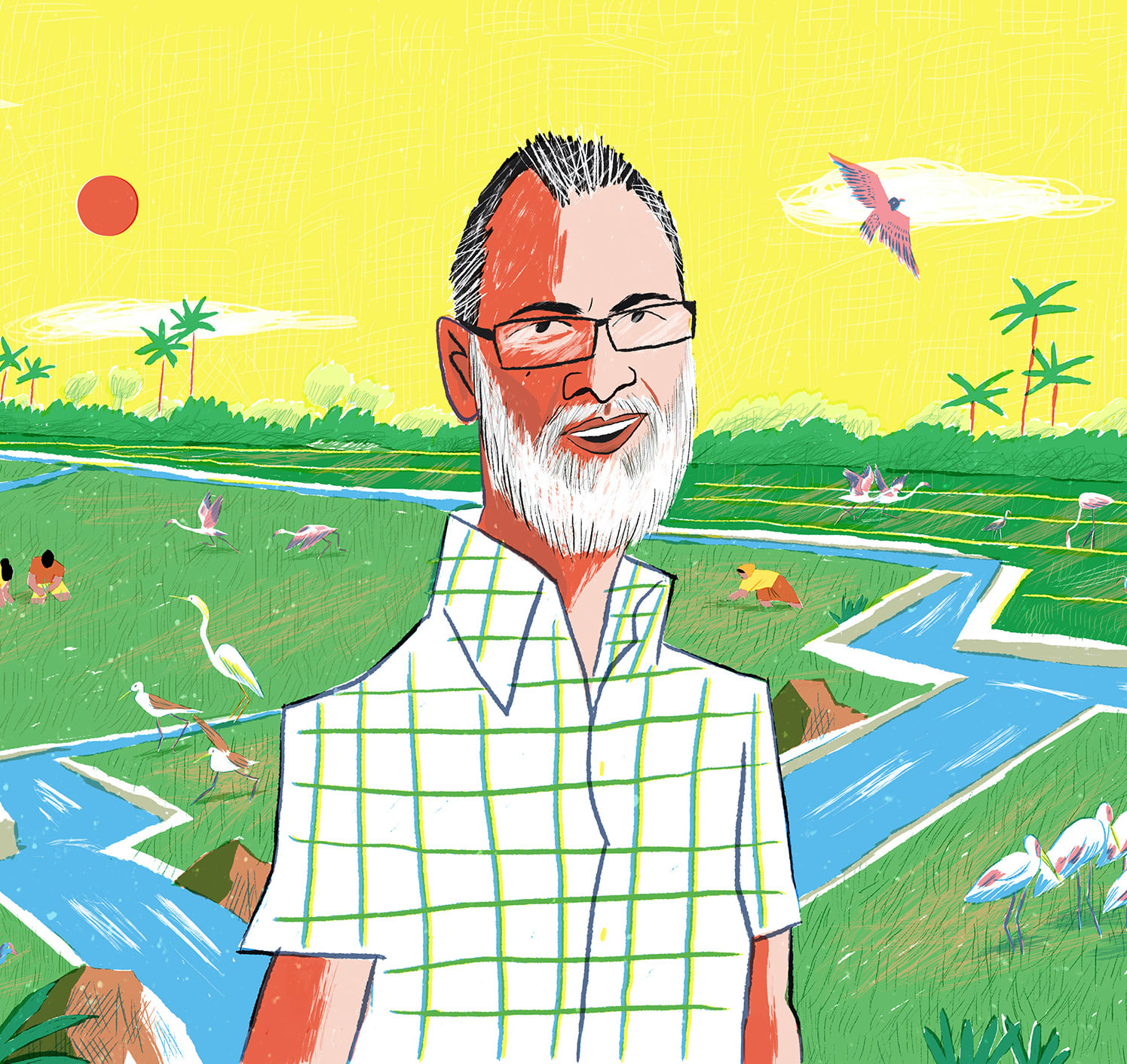

For academics and researchers coming down to study the Vembanad-Kole wetlands, one of India’s 42 Ramsar sites, their go-to person is a septuagenarian agriculturist – Kochu Muhammed.

The president of the Zilla Kole Karshaka Samithi (ZKKS), an umbrella organisation for over 130 farmers’ groups in the region, Muhammed has almost encyclopaedic knowledge about Kole, at the mention of which, he chuckles. “It is true that researchers come to me for information about Kole,” he says modestly.

Quiz him about his five-decade-long association with Kole, Muhammed says it all started when the pull of the land proved too strong to ignore. After completing his engineering diploma, he chose to switch tracks. He says his strong bond or bandham with the wetlands had a lot to do with this decision. “My bandham with this land goes back a long way. I was always interested in these wetlands, and own two cents (unit of land measurement) here,” he recollects.

Kole, is one of the largest brackish, humid tropical wetland ecosystem on the southwest coast of India. Spread over 136.4 square km across the districts of Thrissur and Malappuram, the wetlands are fed by 10 rivers and is a typical large estuarine system on the western coast. Human involvement in the form of agriculture keeps the wetland alive.

Cover photo: The Kole wetland survives with human interference, as paddy cultivation maintains the ecosystem. Kochu Muhammed coordinates over 130 clusters of farmers for an elaborate process of dewatering, storing and recycling water from the wetlands to maintain water in the wetlands. Cover illustration: Hitesh Sonar for Mongabay

Explaining the lay of the land, Muhammed says, “These are low-lying wetlands around 2-3 metres below sea level. During the rain, they double up as a storehouse for excess rainwater, and help control flooding.”

In drier season, when water levels are low, the wetlands are used for cultivation. The farming calendar begins in August. “Before this, we have to pump out all the water and only once this is done can we cultivate paddy. The cultivation goes on till around May. There are two farming systems: double crop and single crop. The double crop lasts till May, while the single crop lasts for about four months,” Muhammed says.

One of the specialties of this wetland cultivation is its dewatering scheme. Each year, before the season starts, all farming clusters, known as padasekharams, have to follow a meticulously planned out calendar to dewater their land before sowing. This is no easy task, considering there are over 130 farmers’ clusters in the region. This mammoth effort requires close coordination among the farms, and also ensures that the drained water is recycled. This ‘collaborative ritual’ or kootaima reeti is what protects Kole as a wetland.

An elaborate process of dewatering, storing and recycling water

So how does this dewatering system work? For the Thrissur Kole wetlands, water comes from the Karuvannur river. Falling under the Chimmoni water distribution scheme, this supplies the water to the Thrissur Kole wetlands. An intensive water canal network weaves through the length and breadth of these farmlands.

The ZKKS has to work closely with the Kerala Land Development Council (KLDC), a state government wing established in 1992 that monitors and chips in with the farming cycle. The KLDC also provides a pumping subsidy to the farmers to ensure that the dewatering is carried out smoothly.

“During the monsoon, the rainwater in the farms flows through the canal network and drains into the sea via the Kanoli canal. Regulators at Enammakal and Idiyanchira in the northern Kole region divert excess water to the Kanoli canal. This ensures flood control,” Muhammad explains.

Breaking down the dewatering process, Muhammed says, “When we need to start with the cultivation, the Idiyanchara regulator and the Kanoli canal system are shut.”

This process ensures the water stored is recycled for farming. “At first, 10,000 acres are dewatered and farming is done. This water pumped out is stored in the canal. After about 15 days, we release this water back into the land so that it is re-used. Similarly, another 10,000 acres are farmed next, and subsequently the third 10,000 acres. Throughout the cycle, the water isn’t drained into the sea and is constantly recycled,” Muhammad says.

A lot of planning goes into this technique of alternate dewatering and storing. It has to follow the assigned slots as per the calendar.

Working closely on this calendar, is a Kole Advisory Committee. “The panel meets once or twice a month to discuss various issues. An executive engineer from the irrigation department is involved, along with other departments to tackle obstacles while implementing the dewatering calendar,” says Muhammed.

For the dewatering activity to be successful, it all boils down to farmers’ synergy. “The water can’t be pumped out by an individual farmer at a time. Everyone has to simultaneously pitch in, and it is this unity that keeps the wetland intact,” the agriculturist says. “All 130 padasekharam committees, big and small, come together for this endeavour. Each paddy field ranges anywhere from 25 acres to 1,500 acres in size, and all are privately owned.”

Muhammed says till date, the whole process has never gone wrong.

This herculean task promises high returns. “The yield is anywhere around 2.5 to 3.5 tonne per acre,” he says.

Revealing the secret behind this high yield, he says, “The key lies in an agricultural crop residue or jaivavalam.” This organic manure in the Kole wetland ecosystem is crucial in providing a booster shot to the bumper crop.

Farming system essential to conserve Kole wetlands

Among the threats the wetland faces, the most worrisome is land use conversion. Jeena Srinivasan, an associate professor with the Centre for Economics and Social Studies in Hyderabad had worked closely with the district administration on the Kole wetlands and compiled a monograph entitled, Agriculture-Wetland Interactions: A Case Study of the Kole Land Kerala in 2009.

During her interactions with the local communities, Srinivasan realised that it was important that farming continued for the wetlands to sustain. “The pressure to convert land use is quite high in this region. If the farming stops, the area would cease to exist as wetlands. Farming is essential to conserve the area.”

P. O. Nameer, head of the department of wildlife science at Kerala Agricultural University (Thrissur), was instrumental in bringing about the Ramsar tag to the Kole wetlands. It was his research paper on Kole that brought the wetlands into the spotlight. “In 1993, there was a national conference on ornithology in Bengaluru, where I presented a paper on Kole as a potential Ramsar site in south India. In 2002, it was declared a Ramsar site,” he said.

Nameer went on to formulate a comprehensive 150-page document, ‘Biodiversity Conservation Plan’ on the Kole wetlands commissioned by the Kerala state forest department. In all the years he worked on the plan, he came to see the farmers’ struggle up close.

“We tried to make it a bottom-up plan. So, we convened several meetings with farmers and all these padashekharams. The wetland is an ecosystem landscape habitat, where human interference is needed. For a paddy wetland, cultivation is the sole factor for maintaining the wetland ecosystem. This human intervention, coupled with ensuring natural succession in ownership is important, otherwise the land would get converted into a forest habitat. A wetland has several ecological functions and a proper hydrological cycle is a must in this area. It stores excess rainwater in the monsoon and guarantees freshwater availability in summer as it this recharges the wells and ponds.”

Nameer attributes Muhammed’s dynamic energy for unifying the different farmers’ clusters in the Kole region. “He knows everything about the area and has ensured that the area remains as a wetland. Most of Kerala’s paddy fields are being converted into other kinds of land use,” Nameer said.

About the economic values of the Kole wetland, Nameer said, “As a highly dynamic system, it performs various functions. Through our socio-economic survey, we found that Kole generates 42 lakh man-days each year. The area earns an income of Rs 12 crore (120 million) through farming annually. This is still a conservative estimate, and the real value may be much more,” Nameer said.

Following the Biodoversity Conservation Plan, Nameer also proposed an incentive or royalty to the generation of farmers who have continued to protect the wetlands for over a century. In 2020, the state government declared in principle that an ecological incentive would be provided to these farmers as royalty for keeping the wetland ecosystem intact.

The wetlands also act as a leisurely pit stop to migratory birds as it falls in the Central Asian Flyaway, a migratory route spanning across a chunk of Eurasia. Nameer, who is also at the forefront of a local community of birders in the area, says Kole is a birdwatcher’s haven. “In 1991, we did the first-ever comprehensive bird survey in Kole. We have continued it till 2020, for close to three decades,” he said.

Manoj Karingamadathil has been an active member of the Kole Birders, a volunteer-driven citizen science initiative 2014. The group regularly conducts bird censuses in January every year, with over 300 on-field volunteers. “It’s been around 30 years since we started the waterbird census. We have around 100 people spread across 15 zones who collect the data. There are around 30 species that frequent this wetland. We do go on bird walks here and share knowledge and enjoy a field experience,” Karingamadathil said.

“We have many species of water birds that are dependent on wetlands for their food. I have observed that the seasons play a major role in governing the birds’ movement. Apart from this, food availability and weather conditions play a major role. So at some stretches in time, the bird count can be low and at times it can get quite high. The time of the survey is really important. At the time when water is drained in Kole, is when a lot of birds arrive,” he said. When water is drained, the marshy zones create conditions for more feed, in turn attracting more birds. “We have a good population coming in. This could be called the number one wetland in Kerala for bird spotting. You can see a lot of threatened species and others migrating from far-off places. These huge flocks number 1,000 birds or higher.”

Meanwhile, Muhammed who recently recovered from Covid-19, has no plans of retiring. “I’m not worried about the future for now. It’s running like a well-oiled machine. Everyone feels responsible for safeguarding Kole as a wetland ecosystem, because all of them have an equal role to play.”

This story was first published in Mongabay India