Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

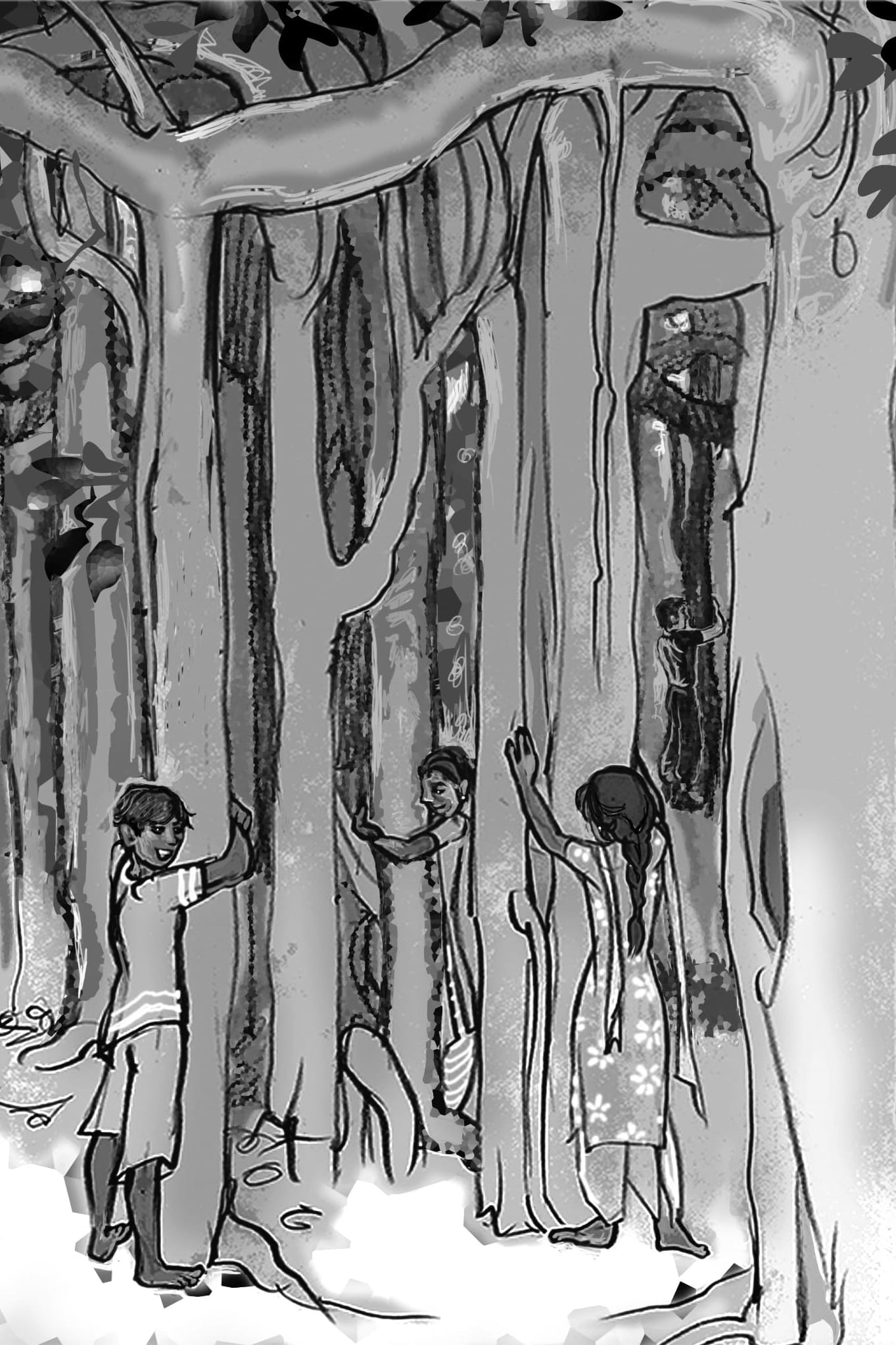

“Despite the softness left behind by the sunset, the roots that hung down from the giant banyan tree near Magundi looked menacing in the shadows cast by the remnant light. The oxen were slowing, fatigued after three days of pulling supplies from Mangalore, but Baab, my father, and Maam, my uncle Paulu, would not stop. Their destination was close, and besides, Voddli Mai (grandmother) told them never to linger near the banyan.

Between the sounds of the wooden wheels of the cart, the bulls’ hooves as they hit the ground, and the clang of bells dangling from their necks, Baab heard a faint “ching, ching, ching, ching”... Maam sniffed the air and murmured softly…

‘A woman in white, heavy-footed, not light,

Feet pointing to her rear,

Musky, when near,

A spirit treacherous

To be faced with caution, not fear.’”

[From: Shades within Shadows by Alan Machado (Prabhu)]

“Musth…” my father replied. “Do you see her?”

“No, but I smell something.”

Banyan trees are bridges between this world and the other, the abode of spirits, planted on the borders of villages. The elders always warned never to shelter under banyans at night because the spirits were about, and not all of them were friendly. Illtreated by a man, embraced by the banyan, Musth roamed Magundi looking for revenge after twilight winked shut to darkness.

Closer to the road by the banyan, they finally saw her. Full of figure, robed in white, radiating a musky scent, she moved towards them, the tinkling getting louder. She looked alive, almost human, if not for her feet which were turned in the opposite direction. Baab and Maam knew she would try to charm them, and they would have to pay a price.

“Poka! What did Voddli Mai say we must do?” Uncle Paulu hissed as he clutched the rosary around his neck.

Baab knew that they couldn’t outrun her. That she would drop the betel nut she always carried and ask them to pick it up, only to knock them out with a blow to their heads if they did. Deve Gowda from the neighbouring estate, found his nephew like this, sprawled with no recollection of what happened to him.

The soft jingle of gejje (anklets) tolled like a bell heralding doom as she approached. Just like Baab had heard, she dropped the supari to the ground, waiting patiently for them to pick it up.

"I remember Paulu! Quick, take off your kachchem (dhoti). Bare yourself below the waist!"

Musth could not stand the sight of a naked man.

And so, your great grandfather and great granduncle reached their destination, safe, with their heads intact and the banyan tree of Magundi, behind them.”

May, in the mountains of the Chikkamagaluru, were full of the chirping of cicadas, mouthfuls of green mangoes dipped in chilli powder and salt, acres of coffee, wildlife, and whispers of ghosts. At the helm of this kingdom was my grandmother, a woman fair of skin, grey of eyes, and strong of heart, nurturing an ecosystem of offspring, relatives, neighbours, with her food and her stories about the land. In her and the ecosystems she cultivated, I began to see parallels with the banyans she spoke of.

Zoologist Robert T. Paine in 1969 introduced the concept of a keystone species. In the simplest of words, keystone species bind other species together. Like cement. Like Grandmothers. Like Ficus trees. They have such a large impact on the systems they inhabit, that if you remove them, the system collapses. Banyan trees (Ficus benghalensis) support large populations of animals that depend on its fruits, on its ecology, and its canopy. But in this, it is a dichotomy, for it begins life as an epiphyte, in the branches of another tree from where it sends roots down. (Epiphytes are plants that grow on other plants.) As the banyan grows, it envelopes the original tree in a poetically beautiful strangling. And life, as it always does, springs from an end and a beginning entwined in one.

The banyan is a woman’s tree; I am certain of this. It is in stories told by other women, just like my grandmother. I have only heard tales of Thimmamma Marrimanu, the largest banyan in the world, remarkable not just in its size but the memory from which it sprang. In 1434, in Kadiri, Andhra Pradesh, Thimmamma, a pious and dutiful woman, well-loved and respected by her fellow villagers, jumped into the funeral pyre of her husband, immolating herself. This banyan was said to have grown from the northeast pole of the pyre, marking her sacrifice. Similarly, in North and Western India, Vat Purnima is observed by married women to symbolically emulate Princess Savitri’s love for her husband, Satyavan. Princess Savitri begged Lord Yama, the God of Death, to spare Satyavan’s life beneath a banyan. Threads of devotion garland the trunks of banyans, year after year, worshipped in memory of this love.

Where the banyan held pain and transgression for Musth, for Thimmamma and Princess Savitri it held devotion. In this dichotomy, it makes space for endurance. Not just in its symbolism but its persistence in a world that seeks to snuff out coexistence and the wilderness. Just like the women in the stories who endured.

On the outskirts of Hyderabad, a motley group of women (and some men) self-assembled under the banner of “Nature Lovers of Hyderabad”, to speak up for nearly 1,000 banyan trees that are being threatened by a road-widening project. The Chevella Banyan Campaign, so named for the banyan trees that line the Hyderabad-Chevella-Bijapur Highway, was started in 2019 as a citizen-led, grassroots initiative to urge decision-makers to make space for nature in infrastructure projects. Their demands are easily achievable: “Replan the project to allow the banyans to be retained as medians with road expansions carried out on either side. Where not feasible, the trees on one side can be preserved, and the road widened on the other.” Over the last five years, their commitment to the fact that we can coexist while we grow has earned them some victories. In November 2023, the National Green Tribunal directed the National Highways Authority of India to conduct an Environmental Impact Assessment with the express purpose of minimising cutting of trees before proceeding further with the road expansion. They endured so that the trees endure.

Keystone species, fig wasps, medicinal curatives, sacredness, we’ve all heard of the magical powers of the trees we’ve lumped together as fig trees. The tragedy is how little research there actually is on the ecology of each of the 96 Indian fig tree species, including the banyan, illustrated by the uninformed proverb, “Nothing grows under a banyan tree”. Kobita Dass Kolli from the Nature Lovers of Hyderabad concurs, “The impact of 914 practically contiguous, large old banyans in maintaining biodiversity and providing ecosystem services is immense. They are true ‘Trees of Life’ in landscapes where they thrive, supporting a whole host of organisms, plants and animals.” Kobita has seen the life that flourishes under and because of the canopy of the banyans, not just along the Chevella Highway but also in the wildernesses she visits.

I’ll end at the beginning, in the story of creation chronicled in the religious texts of Judaism, Islam, and Christianity. It’s a story we’re all well acquainted with, so I won’t retell it. But what I will say is the tree of knowledge of good and evil, whose fruit the serpent used to tempt Adam and Eve, was not an apple tree; it was a fig tree.

We endure because the fig trees endured.