Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Along the road from Coimbatore to Coonoor are several jacaranda trees. Through the higgledy-piggledy confusion of asphalt-grey, these trees suddenly sprout up in delicious emulsions resembling puffy lavender-coloured clouds.

I had never really noticed them before, for ascending a mountain usually involved closing my eyes. With the fast-moving images of tree after tree, and truck after truck my eyes would tire and my stomach, invariably hostile to a drooping vision, would caterwaul with cramps.

I was on my way to a remembrance function. My grandmother had recently died, and had spent many quiet hours in that part of the Nilgiris. She was fond of travel and enamoured by the hills.

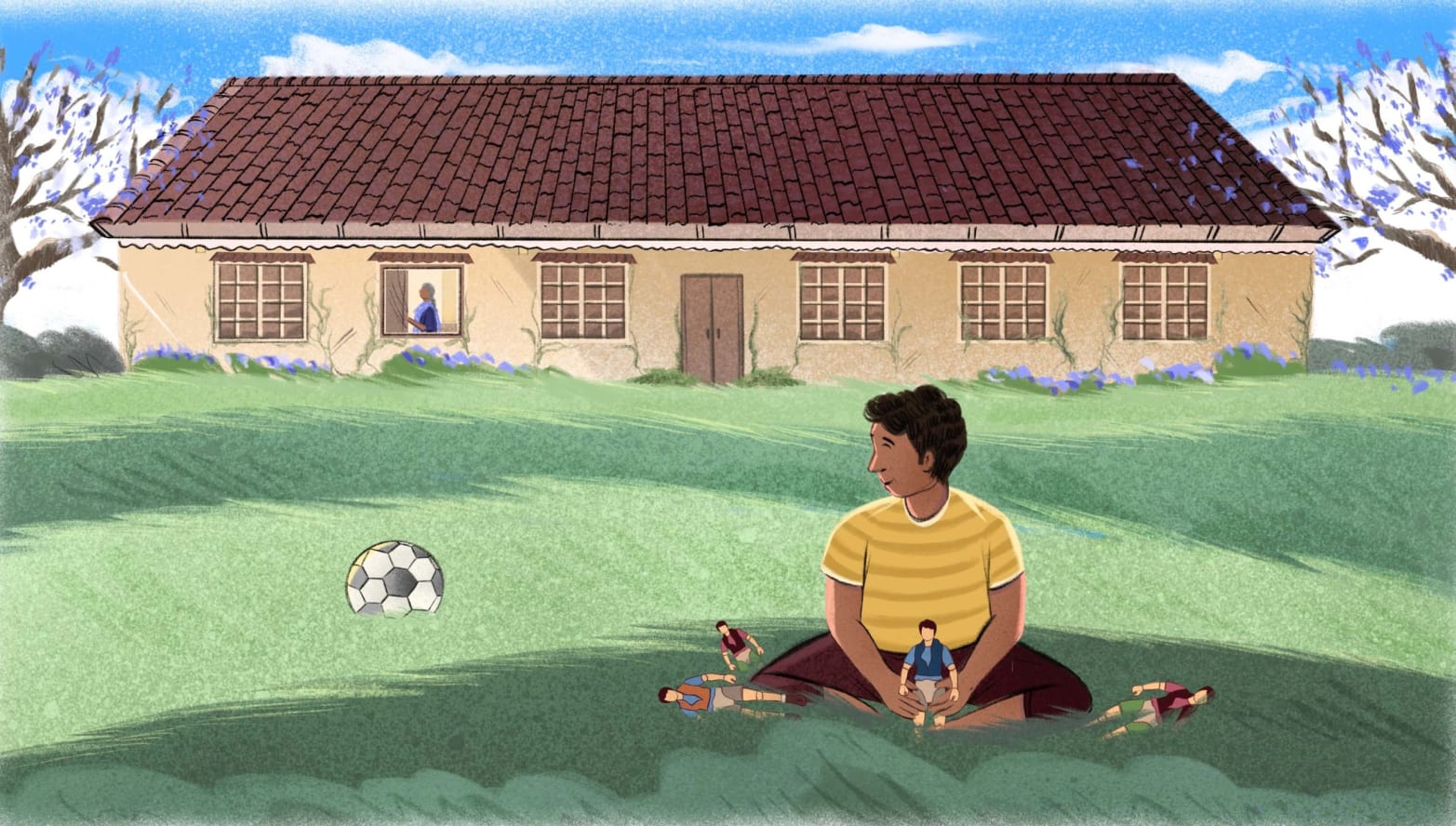

It had been many years since I was last in Coonoor, but the fragrance of eucalyptus and that singular aroma of mountain air cajoled me into a delightful nostalgia. I dropped my bags at the hotel and trundled down the road to my grandmother’s house; the house my grandfather built, and my grandmother frequently visited. As a child, I used to play with custard-coloured action figures in the garden and once bruised my head on the naked stump of stone protruding through the rusty fence. We would kick a football along the wet grass and smell of dew for hours afterwards.

The house itself curiously sits beneath its garden, and creates an effect of being half underground, with the roof visible at eye level. The two narrow roads on either side of the house give it a sense of elevation as for one road travels upward and, the other moves downward. There is a jacaranda tree on both these roads. In the evening sun, the purple of the jacaranda tree seemed to disperse its colour across the water of the blue sky.

Jacaranda trees are originally from the tropical and subtropical regions of Central and South America, with species found in Cuba, Hispaniola, and the Bahamas. The species that grows in Coonoor, Jacaranda mimosifolia, is native to South America. It was introduced to the Nilgiris during the British colonial period, when ornamental trees were planted in tea estates and gardens. I’ve heard it called “blue jacaranda,” neeli maram in Tamil and neelavaka in Malayalam, both meaning “blue tree”. Its flowering season in Coonoor is usually around March and April. The blooms are purple-lavender and last several weeks, after which the ground is covered in fallen petals.

I saw numerous blooming jacarandas around Coonoor’s most popular landmarks. On a morning walk the next day I noticed a massive one, like a colossal chandelier suspended in the ripening matinal light, outside Sim’s Park. Its purple flowers trickled over the wired fence like jellyfish tentacles. Along Brooklands Road stood a solitary jacaranda tree, a serenely resilient ornamentation to the domineering green of the mountains behind. I was soon distracted by a herd of gaur ambling through the sloping tea plantation; their dorsal humps jutting through the evergreen shrubs like lumps of caked lava.

Coonoor is part of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, which holds a rich mix of shola forests and grasslands. The area supports a wide range of birds, and mammals such as Malabar giant squirrels, Nilgiri langurs, Nilgiri martens, leopards, sloth bears, gaur, elephants, and tigers. The botanical garden Sim’s Park has over a thousand plant species, both native and exotic.

My grandmother loved walking along Brooklands Road and probably saw that same jacaranda. Once upon a time, she could walk for hours. Her inquisitiveness to learn and understand her natural surroundings was indefatigable. Her enthusiasm unrelenting.

At the remembrance function, I saw a jacaranda tree. And on our way to Wellington, I noticed another, unwilling to bend to an expanding concrete wall. In the hall of the Wellington Gymkhana are countless trophies, polished and cared for, memorialising the colonial-era slaughter of tigers and gaur, sambar stags, buffaloes, and leopards. The eyes of one leopard seemed alive; as if in abject fear, capturing the precise moment the bullet was released from the colonialist’s gun. I stared into the eyes of each animal. It was a hall that celebrated death, but I was instead remembering life. My grandmother’s life.

I recalled my grandmother’s love for reading — books by Anderson, Corbett, Krishnan, and Thapar. I remember her listening to the birds on our veranda on a sultry evening in Chennai. She loved the colour and scent of lavender, and jacaranda trees reminded me of a sari she often wore that looked as if it were stitched together with jacaranda petals.

I was soon back at her house. It suddenly looked old and senile, disintegrating like ice in the sun. The door was chipped; moss had seized much of the stairwell, roots and vines clogged the drainpipe that skirted the roof. The staircase didn’t seem as large as when I was eight, and neither did the room where twenty of us cousins huddled together and slept. The table we ate our meals at felt smaller, as did the window from which I’d spot my grandmother reading P.G. Wodehouse and giggling to herself under a soft lamp.

The next day, my afternoon nap was heavy with a purple-hued dream. I was walking on a bed of violet and lilac flowers, holding my grandmother’s hand. She was silent. Then, I woke up with a peculiar sense of desperation and rushed to her house again. I lay upon the grass and looked at the sky. It was early evening.

After she started losing her hearing and her eyes tricked her into finding misshapen shadows in the corners of her bedroom, my grandmother became even more like a tree. She would silently watch, observe, and absorb, and her inner world flowered to a point where she could tell, from the touch of my hand, how I was feeling. Towards the end of her life, my grandmother could work magic.

After my trip, I started noticing jacaranda trees everywhere — in Chennai, Ooty, Puducherry. I thought they’d followed me. It was strange to perceive the jacaranda only after she passed away, but it encapsulated all that I knew her to be: elegant, wise, irrepressibly adaptive, with a tranquil beauty. When I hold a jacaranda flower, its softness reminds me of my grandmother’s hands. Sometimes, while leaning against the tree, its flowers brush over my head like her gentle, affectionate hand.

The blossoming of jacaranda is associated with new beginnings in Mexico, and rebirth and change in Brazil and Argentina. But with any change, a steady compass is also needed for navigation — especially for the directionless, like me. That compass used to be my grandmother. But now, in the wind and the sky, in the moonlight, and the shadows, and the soft rustling of the jacaranda flowers, I find her again, guiding me.

She never left.