Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

We were the ‘Kairali Cousins’. In the beginning, God created a girl and a boy – Ammu and Balu. They whimpered and purred. The firstborns were eager to impress and vowed to keep Kairali (our maternal ancestral home) churchy and pious. And then God said, let there be chaos. Out came the rest of us. Four tumbled out one after another, like from an assorted box of chocolates with their unique flavours and colours — some nutty, some bitter, and some amorphous. Unni, Kathu, Malu, and Vichu — the reckless new brooms. All of them, held together by the same DNA, love for kanji (rice porridge), and the walls and floors of Kairali.

Kairali, our home painted in yellow, red, and white with an ‘ambal kulam’ (lily pond) in the front yard and two white pomeranians guarding the house, breathed life into anyone who visited it. It rose with quiet grace amidst a tangle of untamed greens.

‘We are the Kairali cousins,’ announced Malu. And just like that, we became the ‘Incredibles’ of Kottayam.

Kottayam – the land of rubber plantations, surrounded by paddy fields of Kuttanad and the beautiful Vembanad Lake, was home to stalwarts in art and literature. My grandmother was one of them. She was the founding editor of one of India’s leading women’s magazines in Malayalam called Vanitha.

But this story is about my grandfather. He was a botanist. He got paid to be with plants. Throughout my childhood, I thought that was a made-up job. He was just a gardener, maybe a plantation worker. He was ashamed that his job was not as important as his wife’s, and so he sometimes called himself a ‘plant scientist’ and on other days the ‘Director of Rubber Plantation Board’.

On certain mornings when he managed to coax the ‘Kairali cousins’ to go on a trek with him through the hills and flats of Kottayam, he would entertain us with botanical names of every creeper, tree, and shrub that came our way. He would stop to pick flowers of Catharanthus roseus (Madagascar Periwinkle) and Ixora coccinea (flame of the woods), which would later adorn his study table. If we ever played around with the ‘Shame Plant’, he could roll his eyes and say, “Oh, beware of ‘Mimosa pudica’, they are harmful to both animals and humans. (Once, his dog Tommy took many bites of it on a morning walk and was later heard ‘toot-ing and pfft-ing’ till he folded into himself, just like the leaves of the plant, and had to be rushed to the veterinarian.)

I would then string the botanical names together and sing a song: ‘Catharanthus roseus and Ixora coccinea went up the hill to fetch a bucket of tender coconut water, Catharanthus fell down and broke his trunk and Coccinea got stung by Mimosa pudica.’

“Louder, louder mole (dear),” he would giggle, and I would keep increasing the decibels till the trees went deaf.

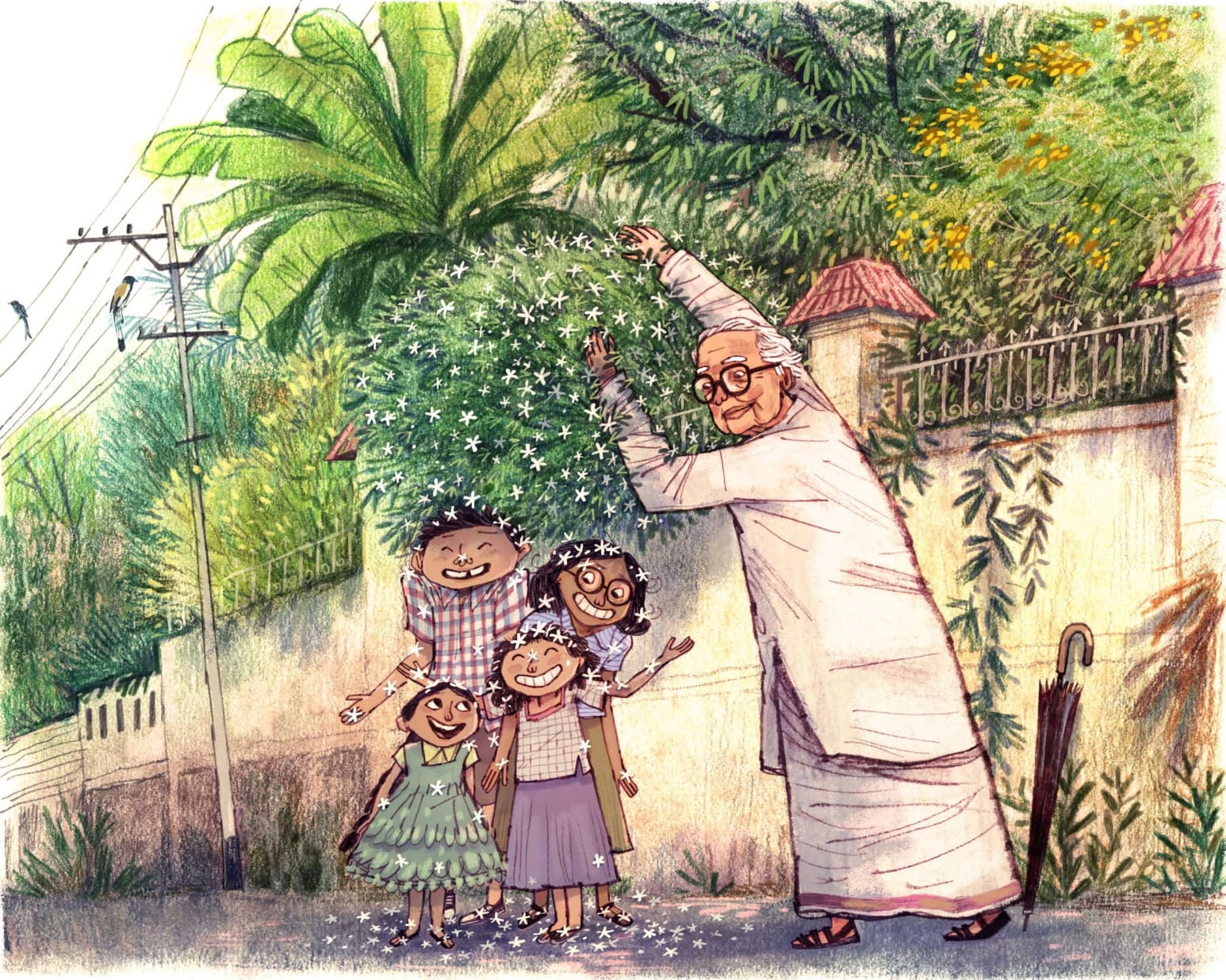

He stopped to greet every flower, every herb, and all the trees in that town. I think he whispered, “Meet my grandkids, they are here to be your friends.” Sometimes, he would ask us to stand under a spreading jasmine tree and shake it with all his might, till we were covered from head to toe in white, fragrant Jasminum flowers. He set aside these mornings to shower the unlimited fondness that smelled like nectar on his dwarf willows.

Kottayam, just like the rest of Kerala, squirmed in the heat from March to May; and this was usually the time that the six of us would make Kairali our assembly point. Like a Maharaja’s summer home, we gathered here for absolution — not just from nagging parents and academic pressures but also from the tropical heat that the rest of the country was writhing in. Our ‘wise old gardener’ would have readied for us, a ‘Thailand water apple’ tree to the right of the lily pond, many ‘Indian coffee plum’ trees around the house, a line of ‘jackfruit trees’, pregnant with the fruit in the parambu (backyard) and like a welcome statue at the entrance door, he would wait for us with a plate full of ‘Irumban Puli (Bilimbi)’ and a bouquet of ‘Kanikonna’ or the golden shower tree (Cassia fistula). Kanikonna used to be my favourite tree, not because somebody named it the official flower of Kerala, but the sight of it signalled the golden period of my childhood. The bright yellow magic carpet of flowers that took me back to my favourite people. All the cousins, entwined and inseparable like vines, prepared to grow in the directions that our grandfather took us in. The man who taught us to honour nature.

In the time that it took the coconut trees to unfurl its leaves, grow roots and start producing fruits, my learning unfolded too. I acknowledged the scientist at home and started reading some of the literature he had written about the most important cash crop of Kerala — rubber. I had no interest in the subject, but I kept reading, hoping that this tapping would elicit invaluable stories from the giant old tree — my Apoopan (grandfather).

I gathered that his love for nature, especially native species, was like an ‘extra finger’. There is an ancient myth in South America that says people who are born with an extra finger are chosen by the Gods. Gods with six fingers visit them, linking six fingers to divinity. I still don’t know if a particular “plant God” used to visit him, but how else do you explain the love story between trees and him?

It’s been eight years since the vegetation of our land has been deprived of him. Every summer, after his passing, I have noticed the golden flower trees getting scrawnier and scantier. The jackfruits have stopped filling me up with their saccharine goodness. We know plants obtain their energy from sunlight, and I think my ‘plant-man’ had the magic to bend the rays of the sun and take it everywhere with him. As he left, he took a lot of that light with him.

Who would believe that we grew up under the shade of such a sacred tree — my Apoopan. This tree is no longer living but if you look closer at each one of us; the ones who sat under it for many years, you will see the roots growing through us, the incandescent heart shaped leaves struggling to keep the fading embers alive and the blooming buds making a promise to tell this story, however incredulous it feels.

I often wonder why the Kairali cousins never found their way back — all of us, together — to say goodbye to the only home that ever truly knew us. Why we never traced our childhood route one last time, winding through the bends of Kottayam, where every turn still carries the echo of our younger selves. Why we never let the wind tangle our grown-up hair as we drove past the teak, the mangosteen and the pepper vines — each one still standing there, bewildered, waiting for the return of the mania we left behind.

Maybe we are scared. Not of going back, but of seeing the place emptied of us. Of catching a glimpse of the coffee plum tree, just a shell of what it used to be, and wondering if it remembers the weight of our childhood. Maybe we believe that as long as we don’t return, Kairali is still alive somewhere — behind that bend in the road, half-wrapped in jasmine scent and echoing laughter.

A version of this story was first written for an Ochre Sky Stories workshop and published on their substack.