Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Whether we have seen an owl in real life or not, most of us know what an owl looks like. Also known as “wolves of the sky”, owls have existed on this planet for almost 60 million years, making them one of the oldest known groups of birds. Out of 254 species of owls recognised worldwide, the good old barn owl (Tyto alba) is the most globally widespread, sharing spaces with humans across different cultures and landscapes.

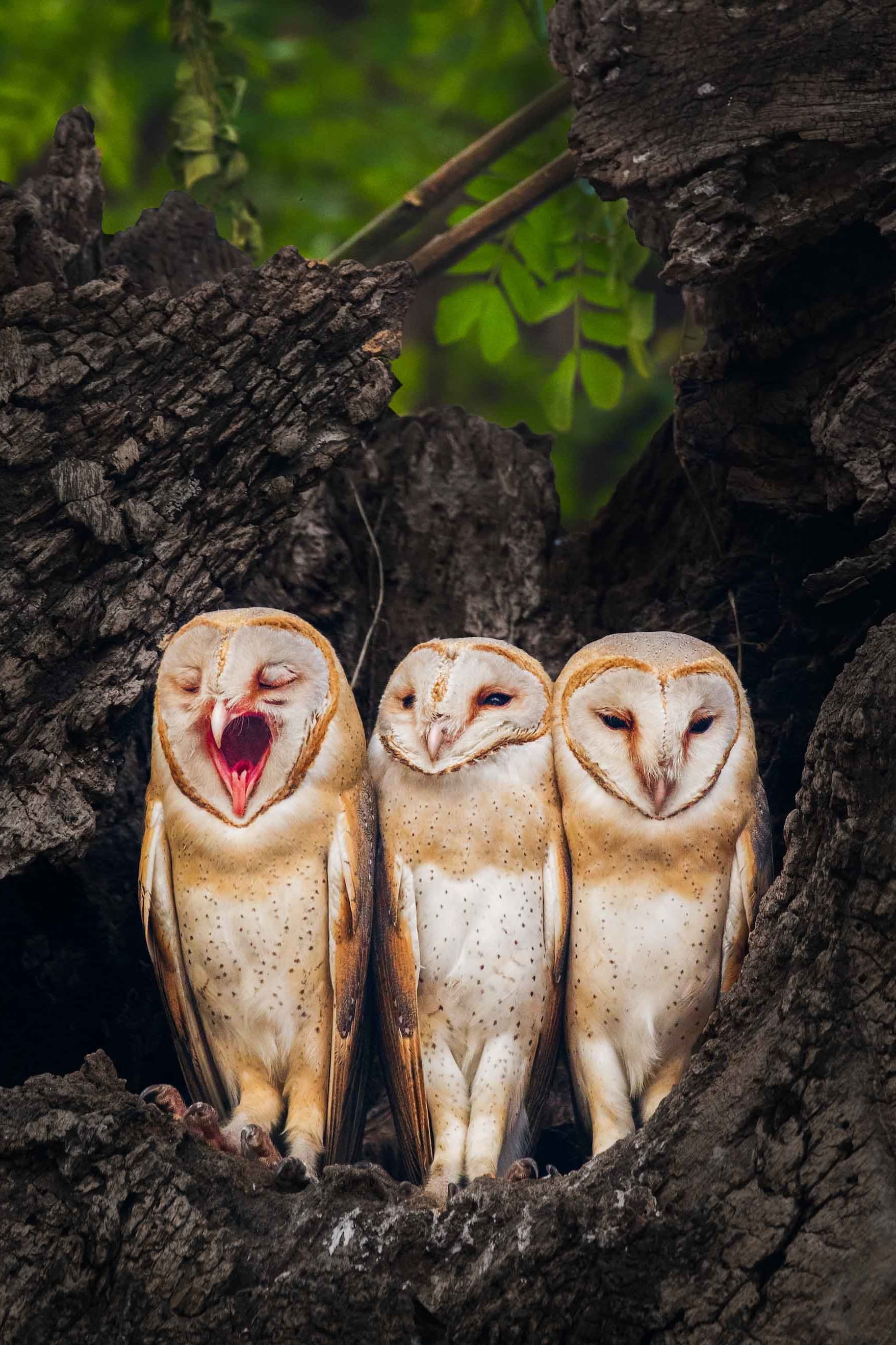

The eastern barn owl (Tyto javanica) is the most widespread out of 36 owl species in India. In The Book of Indian Birds, Salim Ali describes the barn owl as “a typical owl, golden buff, grey above, finely stippled with black and white, silky white below, tinged with buff and normally spotted dark brown. Large round head with a conspicuous ruff of stiff feathers surrounding a comically pinched white monkey-like facial disc. Inseparable from the haunts of man…Emerges after dark with a wheezy screech. The call is a mixture of harsh discordant screams and weird snoring and hissing notes”.

Living in a terrace flat in the peri-urbanscape of Kodigehalli, Bengaluru, I have free platinum tickets to golden, memorable barn owl sightings from my dimly lit, undisturbed terrace after dark.

One clear midnight on 1st January 2024 there was pin-drop silence. Not a leaf stirred. As I edged closer to the parapet on my third-floor rooftop, happily tracing Orion in the sky near a crescent-shaped moon, I caught a sudden soundless movement from the corner of my right eye. Time stood still as a huge barn owl flew out from below the parapet to my right, gliding over my head silently, changing its course as I swivelled my neck instinctively to look upwards, almost colliding with it. Neither of us was prepared to face each other. It was almost a silhouette, but I could make out the beautiful heart-shaped face, the gentle brown speckles on the outspread wings, and the soft primary feathers ethereally outlining its warm, beige body. It took me a good 15 minutes to recover from the surreal experience and reconnect with my other senses, and Orion was almost forgotten by then.

Cover photo: Barn owls are site-faithful, and many generations may stick to the same site. They do not usually abandon a site even if it is no longer hospitable. This makes them particularly vulnerable in cities if they come into conflict with people residing around their nesting spots. Photo: Sourav Mondal

A barn owl uses its acute hearing (which researchers often call “earsight” but scientifically is “enhanced auditory spatial awareness”) to hunt, flying very close to the ground while doing so. It has evolved to nest in cliffs and the hollows of large trees and investigates any dark cavity in its search for safe, dry roosts and nesting sites. Many urban structures simulate its desirable roost sites almost perfectly. Site-faithful and rarely territorial, the barn owl is mostly a wide-ranging generalist, which means it can survive in a wide variety of conditions and changes in the environment, making it a well-suited urban raptor. Additionally, its sharp eyesight and inaudible flight make it a powerful apex predator that hunts mid-level consumers like rodents, ensuring there is structure and balance in the ecosystem. Agricultural scientists are successfully helping farmers naturally control rodent populations by conserving barn owls using artificial nest boxes in Assam, India, the United Kingdom, Israel, Jordan, and California. More recently, the Lakshadweep Islands opted for barn owls as biological agents to control the dramatic increase in rodent populations in their coconut plantations.

So, what can threaten an apex predator? In this case, another large apex predator — Homo sapiens. Although we have walked the earth for under a mere fraction of the time that owls have, we have managed to create unsustainable concrete kingdoms which pose many challenges to these raptors: speeding traffic, high levels of ambient noise, artificial night light, open waste disposal sites, electric wirelines, reflective architecture to name a few.

Humans have also trapped the barn owl in a tricky conundrum. While we have always associated it with Goddess Lakshmi (as her vahana or vehicle) in India, we have also connected it with death, darkness and doom. Apart from the oral retelling of myths and beliefs, we can also find manifold tales, motifs and cultural anecdotes about the barn owl on the internet today, most based on centuries of imaginative storytelling.

We may discover that many of our perceptions of this owl are filtered through a “kulturbrille”, a term anthropologist Franz Boas used to describe the cultural lens that automatically colours the way we see everything. I often get phone calls from people who share their concerns about neighbours wanting to get rid of barn owls roosting nearby because they perceive their harsh screeches as ill omens in the night. As the poet and nature writer Miriam Darlington rightly wrote, “Our closeness has developed over time like a marriage, but not an altogether happy one.”

In a preliminary (unpublished) study conducted with Dr Jayaditya Purkayastha in Guwahati on urban wildlife rescues from 2010 to 2018, we found that the highest rescues were of barn owls. Our ongoing research shows that owl rescues peaked between October and January in the cities we studied. We celebrate major festivals in India, including Diwali and Makar Sankranti during that period, which involves bursting abominably large quantities of crackers at night when barn owls are out hunting. During Makar Sankranti, we fly kites using the deadly Chinese manjha (despite a 2017 ban by the National Green Tribunal on using this string). Additionally, barn owls are captured illegally and sold on the black market in some parts of the country during the Lakshmi puja festival to cater to a disturbing ritual of owl sacrifice (steeped in the misbelief that it will ensure never-ending fortune).

When high-frequency activities like festivals coincide with the barn owl’s breeding season, it can directly affect the birds, as their entire behaviour changes during that time. In January 2024, I observed the night sky from my terrace in Bengaluru suddenly dotted with dozens of perplexed barn owl parents, fervently flying back and forth. They were throwing caution to the wind, trying to cater to their demanding young ones, almost colliding with one another. I could hear the frenzied hissing of juveniles from their nests in the silent night, like hundreds of soda bottles releasing their fizz. The increased hunting and effort adults need to put in during this time automatically puts them more at risk in cities.

Four of the biggest wildlife rescue organisations in the country promptly rescue barn owls and provide effective veterinary and rehabilitation services, leading to successful releases back into their habitats. They are Avian and Reptile Rehabilitation Centre (ARRC) in Bengaluru, RESQ Charitable Trust in Pune, Resqink Association for Wildlife Welfare (RAWW) in Mumbai and Wildlife Rescue in New Delhi. But we need more such professionals and coordination across different cities. As is often the case with urban birds, citizens may place rescue calls or end up handling the owls that need to be rescued in an urgent situation. While well-intentioned, the knowledge gap can lead to mishaps, fatal injuries, and mishandling of grievously injured birds that would have a better chance of survival with professional attention and help.

Pawan Sharma, founder of RAWW Mumbai, shares how, one night, his team attended a rescue call for a barn owl which had been mobbed and injured by stray dogs. By the time they reached, the owl was in a precarious state as well-intentioned citizens had tied its legs (which had multiple fractures) to stop it from escaping until help arrived. Unfortunately, the extent of its injuries and shock meant they couldn’t save it despite the team’s best efforts.

Besides responding promptly to rescue calls, the role of wildlife rescue organisations in bridging the gap between public and professional knowledge in urban centres is critical. Creating spaces where they can provide the necessary awareness and scientific knowledge to the general public can go a long way in fostering and paving the way for community engagement in conserving these urban raptors.

Urbanisation is real and irreversible. As the concrete jungles replace more and more agricultural lands and rural landscapes, we may end up spotting barn owls more commonly in our cities than ever before. This leaves us with a few questions. As citizens, are we prepared to set aside our misbeliefs and adopt a healthy curiosity towards barn owls? Are we willing to support conservation efforts for these raptors in our cities? Or do we choose to be oblivious to the risks we pose for them and hold on to their mythical portrayal in the popular imagination?

Keep an eye out after dark; sometimes, you may make out an odd silhouette in the night sky — a heart-shaped head leading to a boat-like body narrowing down to a tail. Mark my words, the thrill of spotting a barn owl in the night for the forty-second time is as riveting as the first.