Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Hiding behind faded red sandstone walls, the Gajner Palace in Rajasthan guards a treasure trove of intriguing secrets from the past. Outside, beautiful black marble sculptures of big cats line the courtyard, reminding visitors of the palace’s history as a shikargarh or hunting ground. Inside, the corridors come alive with meticulously preserved taxidermied sambar heads and wild boars that once roamed these lands. Within the king’s durbar, the walls proudly display tiger skins and blackbuck horns, bearing witness to the grandeur of royal hunts from bygone eras. However, amidst this display, one feathered creature that made Gajner popular throughout India during the British Raj is nowhere to be found — the black-bellied sandgrouse.

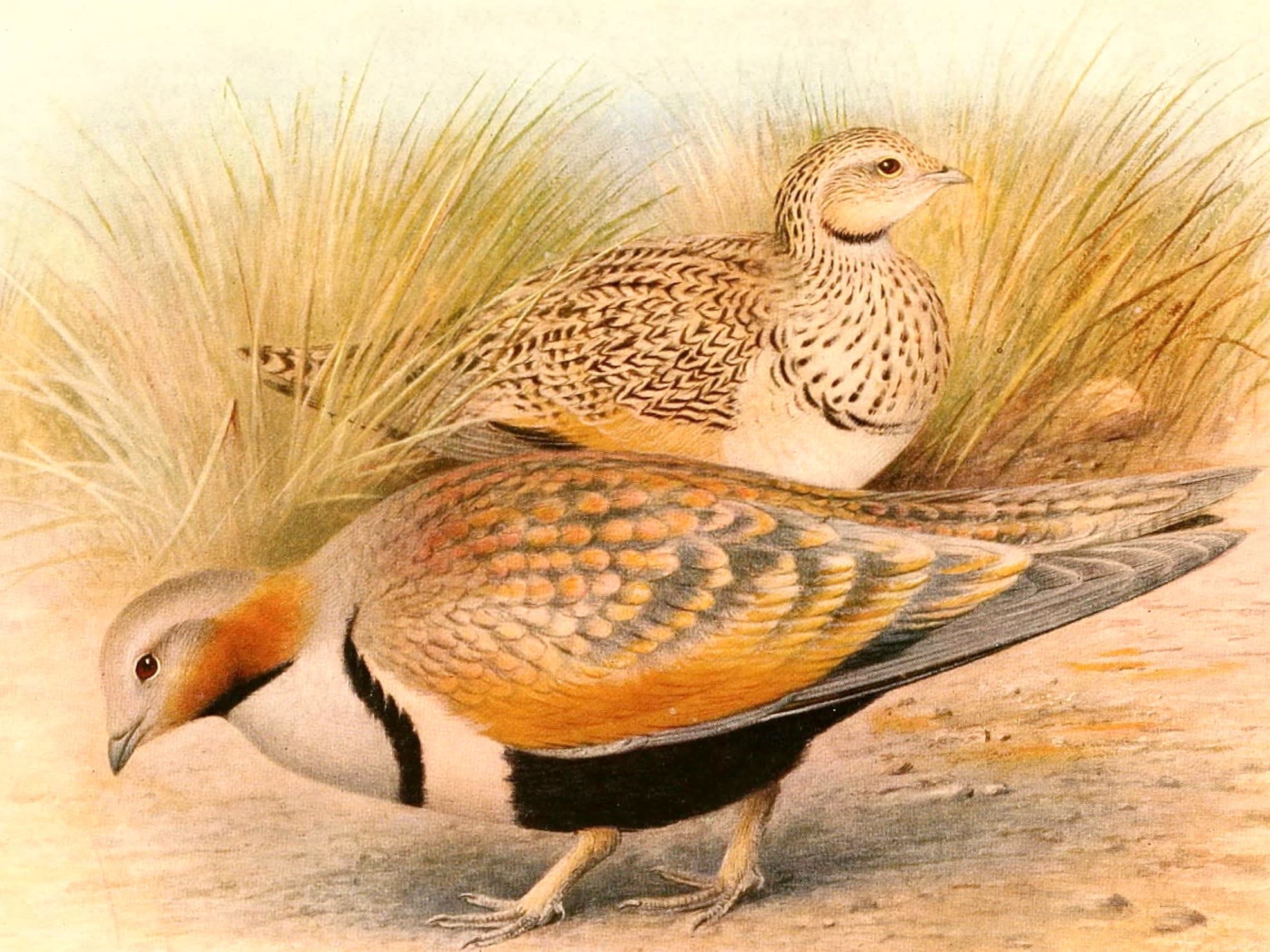

The black-bellied sandgrouse (Pterocles orientalis), once known as the imperial sandgrouse, is a medium-sized bird (33-39 cm length; 300-600 gm weight) characterised by a small head, bulky body, and striking black belly. Migrating populations of this species are known to travel in large flocks from the far corners of Central Asia to the vast desert and semi-arid regions of Rajasthan. It was here, in the late 1800s, that a breathtaking spectacle would unfold between 8 and 10 am, as hundreds and thousands of sandgrouse congregated at Gajner’s waterbodies. During the day, the large flocks would split into smaller groups, searching for tiny wild or cultivated legume seeds. At night, they regrouped at resting spots, readying themselves for the next day and anticipating the end of winter to begin their journey back home. Until the early 1900s, the sheer multitude of sandgrouse journeying to Rajasthan for wintering was beyond imagination.

Cover photo: The black-belled sandgrouse with its small head, striking black belly and pale breast, resembles a pigeon. The female (in the background) is smaller, duller, and more mottled than the male. Photo: Henrik Grønvold, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Let’s go back in time to the late 1800s. Following Maharaja Ganga Singh’s brother’s demise, he ascended the throne of Bikaner in 1887. To an outsider, Bikaner’s vast expanse should have inevitably made it more attractive than other smaller states such as Mewar. However, a stark contrast presented itself: while Mewar flourished amidst a balanced and fertile landscape with ample water supply, Bikaner appeared desolate and dreary. In a nutshell, Ganga Singh’s inheritance came with a realm covered in sand, no proper forests, poor rainfall, and few seasonal rivers at best. Consequently, Bikaner found itself bereft of the abundance of wildlife that graced other states. In an era when Indian royalty faced ongoing challenges to their rule under the British, the rulers often looked for different ways to exercise their authority. Hunting was one such avenue. The question then arose: How could a new ruler like Ganga Singh, whose land lacked big game such as lions and tigers, prove his worth to fellow rulers and his people?

Although Bikaner lacked variety in big game, it more than compensated with its exceptional quantity of game birds. As such, wildfowl figured prominently even in Ganga Singh’s earliest sporting pursuits. The young Maharaja began his first hunting pursuits at age eleven in 1891. By the time he turned 15, his hunting activities had reached new heights when he triumphantly bagged an astonishing assortment of 825 wildfowl, of which 389 were black-bellied sandgrouse. Eager to put Bikaner on the map as a formidable state and popular destination for shooting wildfowl, the Maharaja started hosting a sandgrouse shooting festival in 1895. Little did he know that this festival would soon become sought after on the elite social calendar.

While hunting large animals could sometimes be justified as a public service, such as when dealing with man-eaters, wildfowling faced accusations of cruelty due to the mass slaughter of defenceless birds. However, this sport retained its respectability as long as the game was challenging and there were records to be broken. To ensure this, Ganga Singh frequently extended invitations to esteemed British VIPs to accompany him on his shoots. He emphasised that skill and precise aim were crucial to successfully bringing down these birds, as sportsmen had to accurately target their heads or breasts.

According to the Maharaja, sandgrouse were extraordinary game birds, offering thrilling shooting opportunities. These birds were well-known for their strong and powerful flight, which, to an observer, appeared even faster than their actual speed. Multiple sources also note that due to this illusion of speed, Britain’s Secretary of State for Air compared the flight of sandgrouse to that of torpedo-carrying bombers, highlighting the impressive agility. The fact that these birds loved to travel in enormous flocks, providing hunters with the chance to shoot as many as possible and bag a substantial quantity of wildfowl in a single session, made the black-bellied sandgrouse a perfect game bird.

To be the best at this sport, Ganga Singh constantly looked for unique hunting opportunities for himself and his guests, especially at the annual sandgrouse hunting festival. To ensure a successful hunt, the Maharaja printed letters, schedules, and shooting tips and tricks for his guests. Upon reaching the destination, guests were handed printed hints containing essential techniques and practical tips, including optimal shot sizes, insights into the sandgrouse’s elusive speed, and the advantages of targeting specific body parts. One particular leaflet urged visitors to refrain from the pitfall of excessive shooting and reminded them that “[a]lthough by not taking long shots, one gun may lose some possible chances, another gun will obtain better shots.” He even went to the extreme of providing live targets for his guests to practise shooting.

Unlike big game hunting, where the size of individual specimens mattered, wildfowling records were determined by the number of birds shot. Ganga Singh leveraged this fact to establish his eminence, not only by asserting that Bikaner harboured the most challenging species (sandgrouse, demoiselle cranes and MacQueen’s bustards) but by emphasising the extraordinary abundance of wildfowl in his kingdom. During the best years, he wrote: “when the [sandgrouse] begin...the sight is most wonderful, tremendous big pack after pack come, and many thousand birds drink at each tank.” Entries in the Maharaja’s hunting diary recount instances where, on one occasion, he and his guests shot about 5,968 sandgrouse in two consecutive morning shooting sessions, and on another occasion, they shot about 400 sandgrouse before breakfast. The diary also records him alone shooting about 475 birds in merely 75 minutes. It is estimated that Maharaja Ganga Singh accounted for nearly 25,000 black-bellied sandgrouse kills in his lifetime.

While it is uncertain whether the Maharaja had these birds stuffed as specimens, he did preserve evidence of his wildfowling endeavours. Photographs of sandgrouse hunt bags were featured in souvenir presentation albums. The Maharaja also meticulously documented his wildfowl kills in the comprehensive General Shooting Diary. This diary provided detailed tallies for various species, including the notable sandgrouse.

Historical records from the early 1900s talk of awe-inspiring spectacles from India as thousands of black-bellied sandgrouse flocked to the edges of waterbodies, with numbers ranging anywhere between 1,000 to 8,000 individuals. While the species is of “Least Concern” on the IUCN Red List and its global population is estimated between 130,000 to 260,000 individuals, tragically, the sandgrouse population in India has experienced a sharp decline. Ornithologist Dr Asad Rahmani says that even in the 1980s and early 1990s, he saw “thousands of them all over the Thar desert in winter, including an estimated 8,000 at Gajner, where they had come to drink water”.

However, in the last two decades their numbers have seen a dramatic decline. Why the numbers reduced so drastically remains a mystery. In 2016, a group of 150 sandgrouse were spotted near Jaisalmer. But since then, no more than small groups of 10-15 sandgrouse have been seen in Rajasthan. One theory is that they could have shifted their wintering location. However, there is no evidence of this. But it is ironic that a bird that filled the skies of Gajner even after thousands were shot down every year, can now be counted on our fingers and the once-thriving mass congregations of sandgrouse in India now exist only as distant memories.

Photo sources: cover image, Maharaja Ganga Singh, Ganga Singh with a tiger, black-bellied sandgrouse, taxidermy specimen.