Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

The sky was a deep yellow-orange, with the sun setting behind tall windmills. The windmills were surrounded by rectangular seawater pans, harvested salt along their edges, with saline succulents and grasses lining their embankments. In the foreground of this dramatic landscape, I saw my partner, John, walking towards me, sunglasses on and camera in hand. From a distance, it reminded me of a Top Gun movie scene, but as he got closer, I could see that he was sunburnt, dehydrated, and limping slightly. He was returning from a three-hour quest for the Russian “kuruvi” (birds) in the midday heat of Tamil Nadu. Let me rewind the story to two days earlier.

It was the perfect January morning for an ocean-sunrise-birding trip. We were at Aqua Outback, one of our favourite seaside retreats whose shores are washed by the calm waters of the Gulf of Mannar. Over Aqua, we spotted a new, different species among the egrets, ibises, flamingos, and terns. They first came in ones and twos, their numbers doubling with every passing second. Within minutes, there were thick clouds of them flying southward along the coast. We must have seen a few hundred before losing count. They were lesser black-backed gulls (Larus fuscus) that migrate to various parts of coastal India to escape the harsh winters of Russia or western Asia. These largely carnivorous birds feed on a variety of prey, including smaller birds, mammals, fish, and a range of invertebrates (insects, molluscs, and crustaceans). They may also scavenge on fishing bycatch and carrion. The Indian coastline probably offers them the entire smorgasbord to get through the winter!

In the days after our first sighting, we noticed that the mass of birds was using this north-south flyway at dawn and dusk like clockwork. Where were they coming from? Why did they keep going back to the same spot? We had never before seen so many individuals of one species aggregate in such staggering numbers! We became obsessed with them and were determined to learn more about their lives and how they utilised this mosaic of different habitats. Their roosting spot appeared just beyond the narrow mangrove creek behind the Aqua property. The area consisted of vast tracts of rectangular saltpans and a salt processing factory. It fascinated us that hundreds of gulls spent their winter nights roosting here. “Perhaps we could access it on foot?” suggested John, one evening. With that began our adventure.

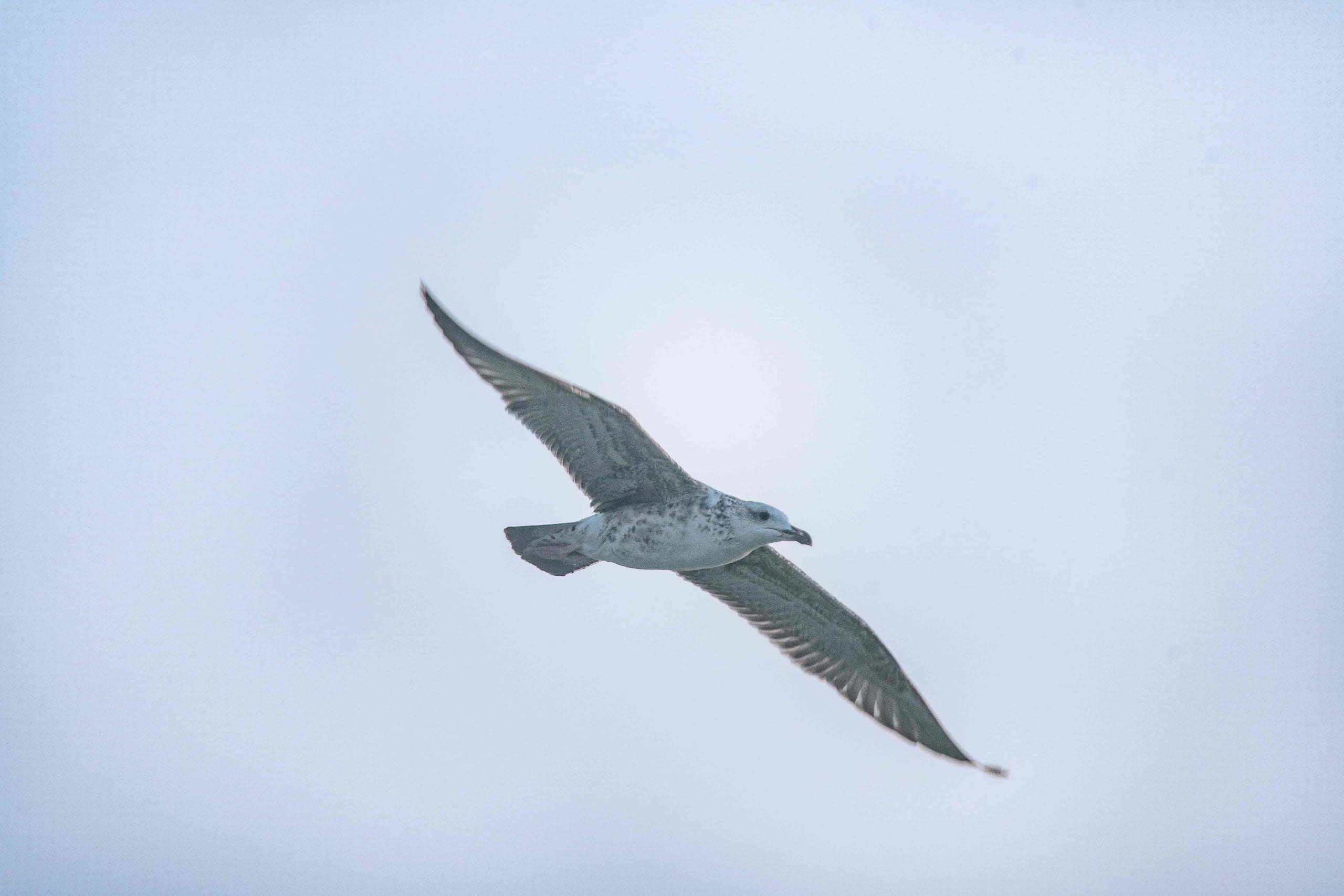

Cover photo: The lesser black-backed gull (Larus fuscus) in its winter plumage flies over the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mannar. This bird would have migrated from Siberia or other areas of Russia, stopping frequently along the way to forage before reaching the Indian coast. Photo: Samuel John

Attempt 1: The wade

At 5.30 am, we thought we would wade across the creek and look for the gulls before they emerged from their resting spot. The creek, shallow the previous year, was now unexpectedly too deep to stand in. As we debated how to cross, a thick cloud of gulls rose some distance ahead of us and headed south. We’d missed seeing them up close but were determined to try again the next day, with a better plan — to swim across the creek.

Attempt 2: The swim

We arrived at the creek at 5 am. John began to swim with his waterproof camera in a waterproof dry bag floating behind him. But a surprisingly strong current slowed him. The gulls were on their way south before he crossed the creek. A more efficient plan was needed. Kayaks, maybe?

Attempt 3: The kayak

On day three, we left a little before 5 am and successfully kayaked to the opposite shore. So fixated were we on crossing the creek that we hadn’t thought about what we would do once we got there. A 12-foot-tall muddy embankment stood between us and the saltpans. Hurriedly and clumsily, we began climbing the muddy wall, dry bag and binoculars slung over our shoulders. By the time we reached the top, our feet were integrated into the mucky earth, our hands caked with mangrove mud. We looked up, and the gulls were already in the air.

Having finally reached the saltpans, we located a few stragglers. We were amazed that the saltpans with their thin film of water mimicked the gulls’ usual roosts on lakeshores and sandbars. We looked for landmarks to help us get closer next time. A blue tarpaulin sheet on one side, a two-storey building on the other, and a few fresh heaps of salt nearby. Looking at the landmarks on Google Maps, we realised that the creek crossing project had been unnecessary because further upstream, a perfectly decent bridge connected the Aqua side of the creek to these saltpans.

Attempt 4: The bridge

At this point, we were leaving by 4.45 am and walking over two kilometres to reach the saltpans. There was good news and bad. We crossed the bridge easily, but landed in a different corner of the saltpan matrix. We could see which saltpan the cloud of gulls was taking off from, but it was too far to access on foot. We were content, though. Following a hunch, we located the roosting site of around ten dozen gulls in what was clearly a busy, human-modified landscape. In the process, we also saw a large female short-eared owl, a ground-dwelling migrant from Europe, perched in the thorny vegetation beside the saltpans — wholly unexpected!

When our friend Umeed arrived, we updated him with details of our weeklong gull saga and how their nightly roost had been too far to reach on foot. Umeed kindly said, “I have a car, I’ll take you”.

Attempt 5: The drive

Waking up before gull’o’clock the next morning, we piled into Umeed’s car and drove there. Spoiler alert: We missed the gulls again, by a few minutes, due to taking a wrong turn. However, some saltpan workers suggested driving to the beach, where we might see a few gulls. Sure enough, we found hundreds of lesser-black backed gulls huddled together on a tapering sandbar jutting into the sea. A truly glorious sight.

At first, it seemed odd to observe these birds sitting on the ground in flocks, given that they are excellent flyers, covering long distances twice a year. These gulls, however, do spend a lot of their time on the ground. During the breeding season, they return to their summer homes and nest on the ground, often near shores or on cliffs, within the safety of large colonies. Both parents are invested in caring for their young, from incubating the eggs and finding food to protecting and raising chicks.

Attempt 6: The stars align

On day six of the quest, we left in the dark, at 4.30 am. We navigated the highway, entered the neighbouring saltpans, wove through a maze of rectangles, counted saltpans, tarp sheets, houses, and salt piles. A bustling marketplace of squawking gulls had taken over the soundscape of the saltpans. Soon, hundreds of bobbing white heads came into view in a saltpan ahead of us. Umeed stopped his car and switched off the lights. Hundreds of lesser black-backed gulls were packed together like animated dolls in a box. We were finally within two hundred metres of the birds!

We watched them preen and squabble, fidget restlessly, waiting for a cue. And as the sun began to rise, it came. Somewhere in the flock, a flapping of wings began — a signal that it was time. Within seconds, a wave of wings took to the sky. That day, I realised that the organised flight formations we see in the sky are preceded by moments of sheer chaos. Loud squawks, fluttering wings everywhere, and a deluge of tiny loose feathers falling to the ground. As the birds took off, like thick clouds swirling into the sky, the sound of hundreds of pairs of feathered wings flapping could best be described as similar to the “hissss” of snakes.

Our gull tracking adventure made us appreciate the importance and thrill of extended observation and going beyond merely identifying animals and making lists. Although our quest ended that day, many questions remained unanswered. What food source sustained such a large population of carnivorous birds on the coast of Tuticorin? Shrimp farms? The harbour? Why weren’t they present in these saltpans in previous years? Perhaps another natural history adventure awaits!