Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

When you are suddenly awakened at 3 am by the hysterical “may-yew! may-yew! may-yew!” caterwauling of the peafowl (Pavo cristatus) living in the historical Nicholson Cemetery next door, you stir uneasily in your bed. Has an interloper sneaked into the place and is even now scaling the boundary wall to enter your home with evil intent? Or have ghosts dwelling in the cemetery simply returned from a night on the town rapping and drinking at the “Rattlin’ Bones” nightclub?

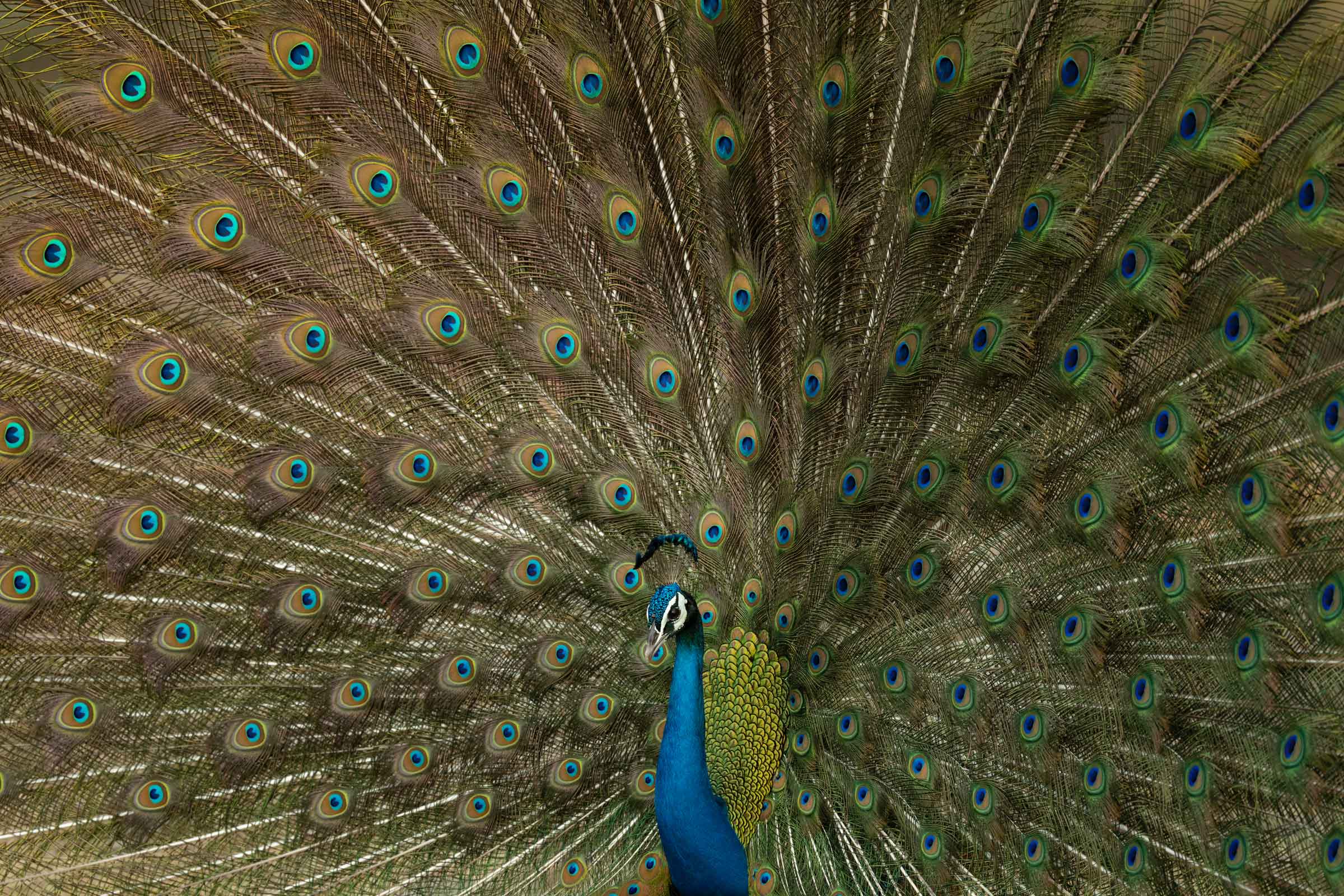

We know for a fact that peafowls are excellent watchdogs, and in the dry and moist deciduous jungles they inhabit, they warn the entire forest of the progress of a tiger seeking its dinner. As they are our national bird, every patriot knows what they look like and will duly gasp with admiration when they behold them. The gentlemen, that is, the peacocks. The peahens, alas, in their dowdy brown shawls and minus the magnificent cloak, win no such admirers, though they are the ones who really hold the reins of power. But first, to clarify, that magnificent iridescent cloak that the peacock trails behind it, with its breathtaking blue and purple “eyespots”, which may have more than 200 feathers, is not the tail. It is what ornithologists term “upper tail coverts” (feathers covering the top of the tail). A peacock in full regalia may reach 225 cm in length and weigh up to 6 kg.

Cover Photo: Native to the Indian subcontinent, the Indian peafowl is the largest of the three peafowl species found in the world. The male bird has metallic green tail feathers with iridescent ocelli (eyespots) ringed with blue and bronze. Cover Photo: Shreeram MV

The peacock’s magnificent train caused none other than Charles Darwin such extreme annoyance that he wrote his friend and American botanist Asa Gray that “the sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze at it makes me sick!” Surely no bird dragging such an encumbrance behind it could survive very long — it went against his theory of natural selection. So Darwin proposed another theory to explain this: sexual selection. Basically, in the case of peacocks, gentlemen with the most flamboyant trains were indicating to the ladies, “look girls, despite this enormous tail, I am so fit that I can escape from leopards, tigers and the like – so if you partner with me so will your babies!” And escape it does. I suspect that the tail has “survival value”, too. For instance, I’ve seen a bird vanish into the forest as the tail coverts turn into a cloak of invisibility. One moment, the bird is there with its fan resplendently outspread like a galaxy of planets as it dances. The next moment, it’s gone, folded up, it merges perfectly into the verdant jungle around it as the bird sneaks off, running for cover, head down as if under fire.

When the male dances, the ladies, who move around in groups of four or five, will feign indifference. He zithers and waggles his russet wing feathers (even displaying his backside to them!), his stiff fan quills quiver and shimmer — hypnotizing in their beauty. The iridescence of the feathers, the ever-changing sapphire blues, bronze-greens, and coppers are caused not by pigments but by the reflection of light on the feathers, which absorb certain wavelengths (red) and reflect others (blues, greens and purples).

I’ve watched gentlemen duel over ladies in the cemetery amidst the tombstones. Screaming at each other, their gorgeous throats palpitating, kohl-lined eyes glowing, they face one another and then fly at each other, more often than not, failing to make contact. They land, swirl around like medieval jousters, and prepare for another round. They have spurs on their legs, so it’s better that no contact is made. Eventually, one bird tires and flees and is raucously chased by the victor, who returns to his “lek” (the small area where he performs his courtship display), crowing victory.

On one occasion, I watched the final act of the drama: a gentleman was covering a lady, who was squatting quietly in front of him, his train outspread over her, almost mantling her.

A high cement platform in the cemetery was the stage where the males preferred to perform, to be watched by the ladies — but it seemed that the ladies, too, had a strict hierarchy. Only the top-ranking lady would fly up to this platform to watch her suitor and would drive away any others daring to take a peek.

Debate still rages over whether sexual selection is behind the peacock’s extravagant train. Some researchers from Japan have shown that ladies do not necessarily prefer gentlemen with the most magnificent cloaks (published in Animal Behaviour 75(4). They are still arguing over the real reasons, with complicated genetic, hormonal, and even geographical causes cited and no definitive agreement reached.

Peahens lay 4-6 oval buff-white eggs in a scrape on the ground, a parapet or porch, or the flat roof of a house. The eggs hatch after around 28 days, having been incubated by the mother alone. The chicks are nidifugous, i.e., able to care for themselves from the time they hatch.

The birds are omnivorous and will eat everything, including foodgrains, berries, fruit, seedlings, insects, small mammals, frogs, lizards, snakes and anything you plant in your garden. But as they also consume vast quantities of voracious pests — like grasshoppers — they are forgiven for their other sinful eating habits.

Peafowl calls can range from the familiar “may-yew, may-yew, may-yew!” to a frantic “tok-tok-tok” and a brassy honking as they fly to or down from a perch. Researchers have identified as many as six separate alarm calls. Moms will constantly utter a soft “chuck-chuck-chuck” as they lead their broods along, perhaps teaching them what’s edible in your garden and what’s not and why they must avoid cats!

Peafowls are found all over the Indian subcontinent, breeding in April and May in the south and from June onwards in the north. After the breeding season, the gentlemen promptly dispose of their cloaks — dropping their plumes —which we eagerly pick up and make into fans”, often sold at traffic lights. (Sometimes, the birds are caught and plucked — this is illegal). Peafowls have travelled abroad too and are now found in several countries, including the USA, where they strut around as ornamental birds in parks and gardens. In forests — and the cemetery next door — they will fly up to the tops of trees to roost every evening and keep a watch on the goings-on below, ever ready to let forth that banshee-like shriek if required.