Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Visualise a small creature with limited mobility, lots of brittle, easily broken spines, and no brain. It has thrived on this planet for over 450 million years, survived mass extinction events, and evolved into 950 species worldwide, of which around 150 are known to be found in Indian waters. Sea urchins are small, round, spiny creatures found in all the oceans of the world across a range of temperatures, depths, habitats, and water conditions.

Their spines are the defining characteristic of this group of animals. The word “urchin” was derived centuries ago from a French word meaning “hedgehogs”, and it is apt since these creatures are spiky and round. Sea urchins belong to the phylum Echinodermata, a word that roughly translates to “hedgehog skin” — another reference to their spiky appearance.

Sea urchins are as diverse in appearance as they are in the habitats they occupy. They come in shades of black, brown, green, and red, with spines that are short, long, sharp, blunt, or club shaped. Many species have two types of spines: long primary and shorter secondary spines. While most of them have a round body, some urchins, like the sand dollar, are flatter with hair all over — adapted to life in shallow water and sand. The largest sea urchin is the giant red sea urchin (Mesocentrotus franciscanus), averaging more than 18 cm in diameter, while the smallest sea urchin is a sand dollar (Echinocyamus scaber) which is barely 5.5 mm in diameter.

Cover photo: Sea urchins are among several marine life forms that are extremely resilient, adaptable and have persisted on this planet for millions of years, thriving in all oceans of the world today. This is Temnopleures sp. Photo: Phalguni Ranjan.

No eyes, all spines

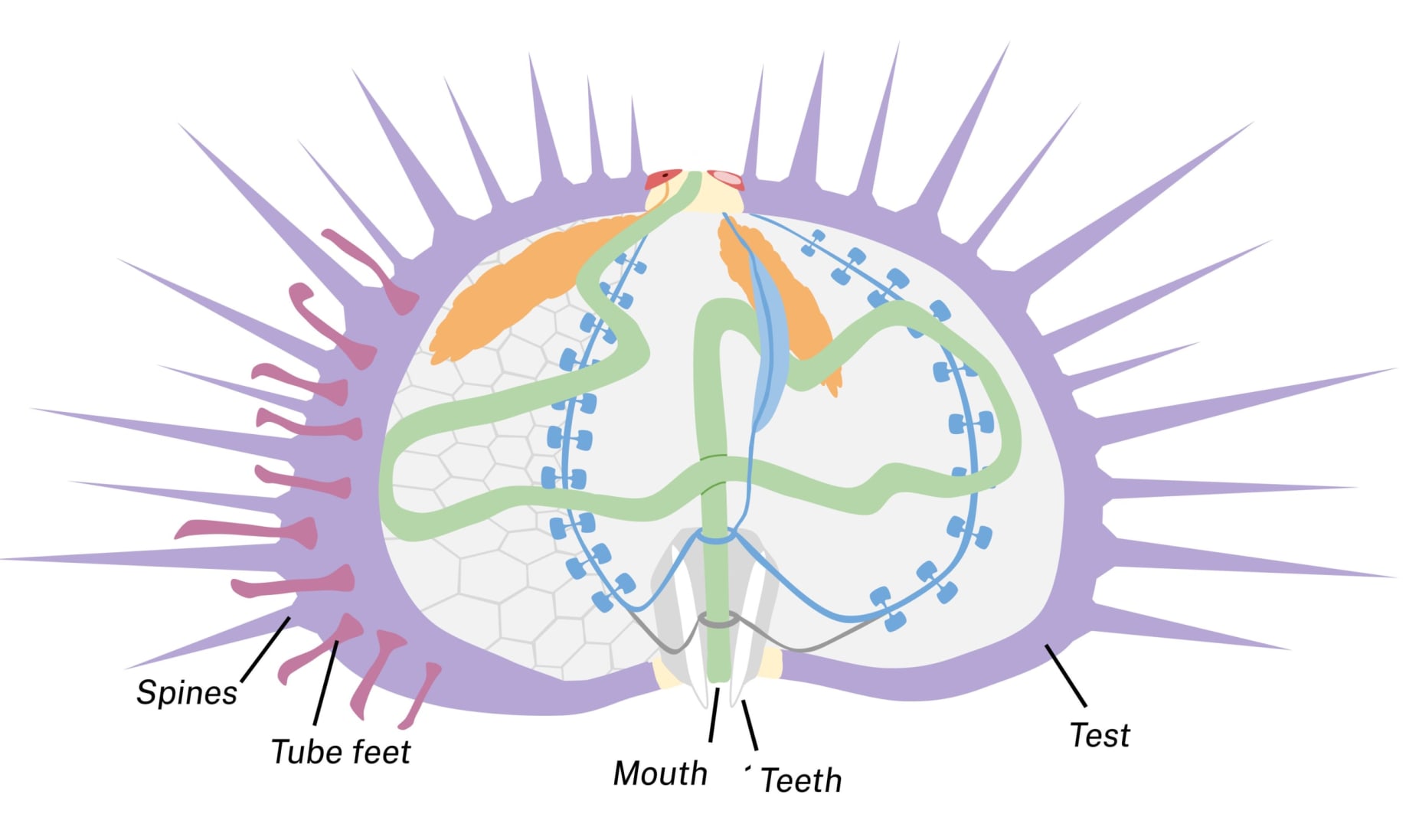

Most sea urchins do not have eyes; they have light-receptor cells in their tube feet that send signals through their rudimentary nervous system. Tube feet are tubular appendages with suckers at the end, that are present on the underside of the sea urchin. They are equivalent to having feet, but apart from locomotion, they also carry out feeding, respiration, and chemoreception (response to chemical stimuli). Situated on the underside of the body, a sea urchin’s mouth is an intricate muscular system comprising strong jaws and five teeth-like structures. These “teeth” can move in different directions and graze on algae or other vegetation.

Urchins do not have a brain or a proper nervous system like that found in vertebrate animals. They have a central nerve ring surrounding the mouth from which five main nerves extend into the body, branching out further to reach the tube feet, spines, and pedicellariae (small, pincer-like defensive organs on the sea urchins’ body). As with all other invertebrates, sea urchins lack a spinal column and bones. However, they have a tough outer shell called a “test”, which is largely made up of calcium carbonate (along with a supportive framework of interlocking crystals of minerals like calcite and magnesite). The test is a porous, sponge-like ball reinforced by interlocking plates and spines — a meshwork structure called a stereom.

For people, injuries caused by sea urchin spines can be extremely painful, made worse by the brittle nature of the spines that can break easily and stay inside the wound. Aside from the risk of infection this poses, some urchins are extremely venomous, and stings can cause death in severe cases. The disarmingly pretty flower urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus) is recorded to be the most venomous sea urchin, and stings can cause paralysis, breathing difficulties, and numbness. Though not a common sight, some old records suggest it might be found in Indian waters as well.

Feeding and biology

The average lifespan of a sea urchin in the wild is about 30 years, but it has been observed that their longevity decreases in captivity (such as in labs). Some species have been recorded to live for more than 100 years, with some individuals even surviving up to 200 years in the wild.

Sea urchins are omnivores; their diet includes marine worms, algae, small sponges, and other small invertebrates. Their predators include lobsters, crabs, large fish like wrasses and triggerfish, sea stars and sea otters. These predators employ various clever techniques to get past the sea urchin’s sharp spines and hard test to reach the soft insides.

Resilience and ecological balance

Sea urchins are extremely resilient, and some species, like the purple sea urchin, can survive food scarcity by going dormant for several years. However, despite their resilience, they are still susceptible to threats from diseases and parasites, over-harvesting for the food industry in some parts of the world, and ocean acidification due to climate change.

Sea urchins have a role to play in the ecosystem, and like all elements therein, their population fluctuations can also affect the balance of the ecosystem. Like parrotfish, surgeonfish, and rabbitfish, they belong to the category of grazers that maintain the balance between algae and corals, thus, keeping a reef healthy. Unfortunately, in several parts of the world, sea urchin populations have been increasing dramatically. Several factors, including overfishing and climate change-induced habitat loss, have resulted in declining populations of the sea urchins’ natural predators. With fewer predators to keep the sea urchins in check, they have been increasing in number, resulting in a decline in the kelp forests along the coast of California and Alaska, and seagrass habitats in Kenya.

Forks, folklore and pharma

Sea urchins are a delicacy in many cuisines around the world. They are eaten raw, seasoned with lemon or olive oil, added to sauces, or used to flavour other dishes. There are around 18 edible species of sea urchin, of which the green and purple sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus sp.) are the key ingredients in uni sushi. About 80 per cent of the world’s commercial urchin supply is consumed in Japan, where the sea urchin gonads and roe (egg masses) are delicacies. Interestingly, despite being a rare and sought-after global delicacy, sea urchin consumption along India’s coastline is still uncommon and limited to very small pockets.

Representation of urchins in folklore and culture varies from them being considered totems and symbols of fertility, to mythological records of them as protective magical symbols and good-luck charms. In a few small places in southern India, sea urchins are harvested for food, and the empty tests are sometimes repurposed as lampshades. In other parts, the intricate meshwork of the test inspires ceramic artwork and curios.

More intriguing is the relatively recent discovery that some sea urchin species contain unique organic compounds that have antioxidant, antidiabetic, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties, making this animal pharmacologically important.

Regardless of their importance in cuisines and cultures, sea urchins are a classic example of what can happen when the delicate balance in an ecosystem is disturbed. In many cases, if the ecosystem is left to recover, this ecological balance can be restored. However, under sustained pressure where the ecosystem is unable to recover, these disturbances can result in permanent changes and shifts away from the original ecological state, that are currently being observed in some parts of the world.

Photo sources: anatomy, flower urchin