Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

My appreciation for sea kraits has grown over the years. My first encounters with these marine reptiles were mostly on land. In my early years in the Andaman Islands, we spent many nights accompanying fellow researchers on long walks on the beach. It was no “secret” that sea kraits spend a lot of time out of the water, and the Andaman and Nicobar Environmental Team (ANET) was studying the behaviour of these animals when they came ashore every night.

It was extraordinary to see these snakes go from swimming to crawling out of the water, without the clumsiness some of us exhibit as we tumble out of the waves. Sea kraits are unique among sea snakes in their dependence on the terrestrial environment. They need land to rest, digest, shed their skin, look for mates, and lay their eggs. In some places like New Caledonia, yellow sea kraits (L. saintgironsi) nest together in “nurseries”.

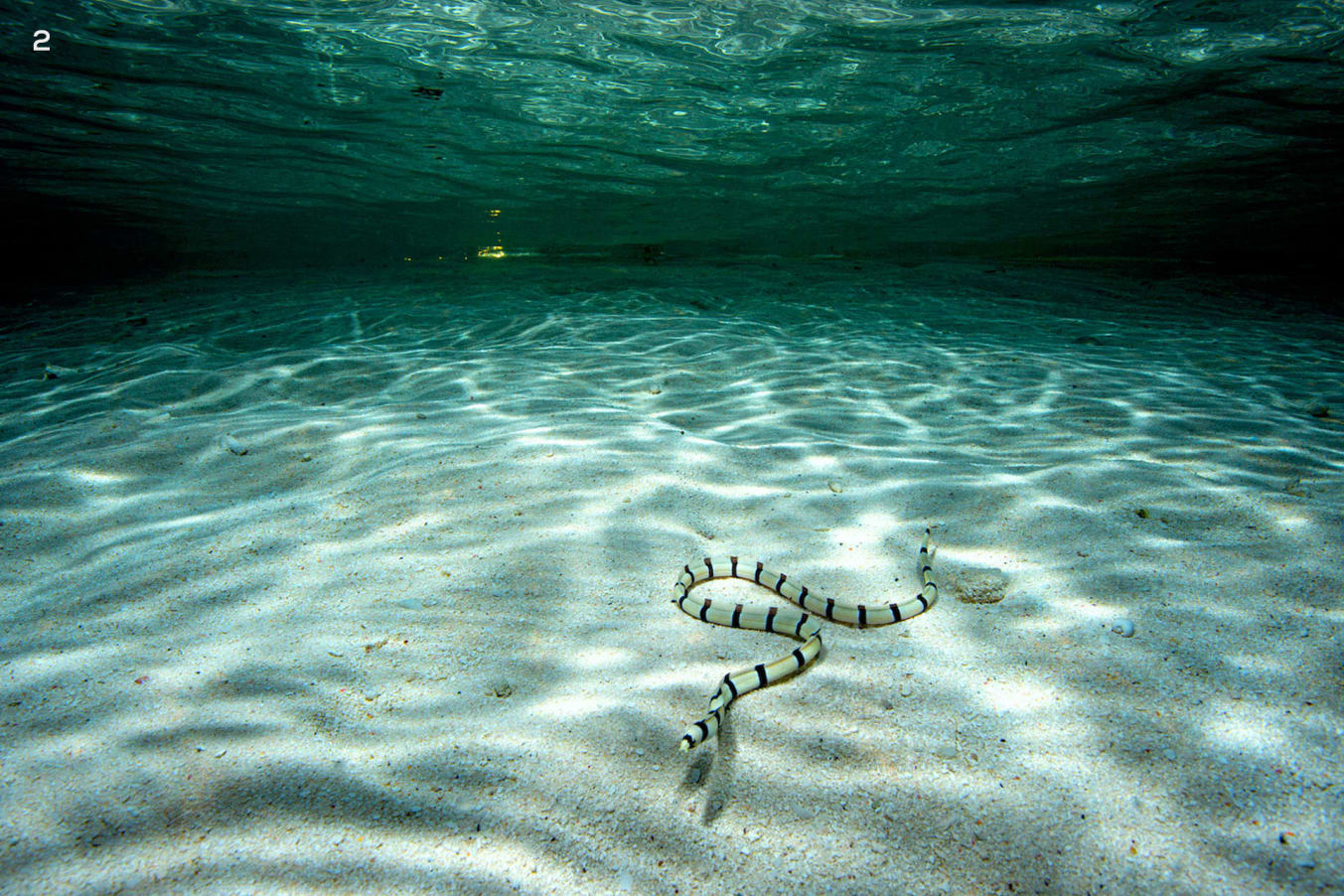

Cover photo: Yellow lipped sea krait (Laticauda colubrina). Photo: Dhritiman Mukherjee

My fieldwork involved diving to measure and photograph corals in the Andaman reefs. Coral reefs are extremely diverse ecosystems with a plethora of life, and paying attention to anything other than my study subject was a distraction. Top on my list of favourite distractions were sea kraits.

Underwater, sea kraits tend to look rather busy. As active hunters with a specialised taste for eels, they are perpetually on hunting excursions. Eels often hide in crevices and burrows with only their heads exposed. They are strong, girthy and equipped with two pairs of jaws. To catch these eels, sea kraits first administer a venomous bite laced with neurotoxins that cause paralysis. It’s easier for them to swallow an incapacitated fish whole.

Despite the potency of their venom, sea kraits are extremely gentle snakes and are ideal candidates to demonstrate that being venomous does not always equate to being dangerous. They save their aggression and precious venom for feisty eels. In some parts of Indonesia, black-banded sea kraits even form social parties with yellow goatfish and blue-fin trevallies to better hunt prey.

I began to understand just how incredible sea kraits are only after I started working as a dive professional and took people diving to introduce them to the marine life on coral reefs. Following a sea krait, understanding its natural history, observing its behaviour in the wild was a part of the job.

Sea kraits, like other sea snakes, have evolved from terrestrial reptiles. In addition to retaining a few land adaptations (large belly scales to move easily on land), their bodies are equipped for an active predatory life in a perpetually moving, salty, pressurised water world. Sea kraits have a streamlined body, a modified “saccular lung” and a flattened paddle-like tail that makes them great swimmers underwater.

Alongside dive guiding, I began learning how to “free dive” or “breath-hold” dive. Breath-hold diving is the practice of being underwater without an assisted air supply (like a SCUBA tank). How much time you get underwater is determined by how long you can make the air you last sipped on the surface, last. Learning from the best teachers, it took me several attempts to become comfortable with the technique, to not thrash at the surface, and stay calm for longer durations underwater.

Sea kraits can stay underwater for up to 30 minutes, and free dive down to 80 metres before surfacing for air. They need to be functional underwater, hunt down prey, manage their buoyancy, fight currents, swallow their prey, and make it back to the surface in time for the next breath. They make it look effortless, every time.

There are eight species of sea kraits found between the eastern part of the Indian Ocean and the west Pacific, and they are some of the most graceful animals one can witness underwater. However, sea kraits are threatened by everything from getting caught in nets as bycatch, to losing their prey and habitat, overharvesting, coastal development, and climate change. Additionally, by virtue of being venomous reptiles, they often don’t garner as much respect and appreciation as their sea turtle relatives.

Today, with ocean experiences becoming more accessible — through diving and snorkelling — people are getting the opportunity to spend time observing otherwise misunderstood animals like sea kraits. There is reason to hope that our perceptions of these animals will shift from fear to awe, as they show us with utmost elegance how best we can navigate the challenges of this changing world. We can start by taking a deep breath!