Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

After eight years of living and diving in the Andaman Islands, I only need one hand to count the times I met a shark underwater. The number is five. One of these instances occurred on a dive at Minerva’s ledge, a flat football field-like coral reef off Havelock Island. With mostly young recovering coral everywhere, the only available shelter for bigger animals is the large oddly shaped rocks strewn around the reef (like menhirs from the Asterix comics). Minerva is spectacular not because it is packed with life in every corner but because it is vast, unpredictable, and often throws up surprises. Some surprises have included a pod of dolphins, schools of sweetlips, free-swimming moray eels, and rare butterflyfish, but until then, never a shark.

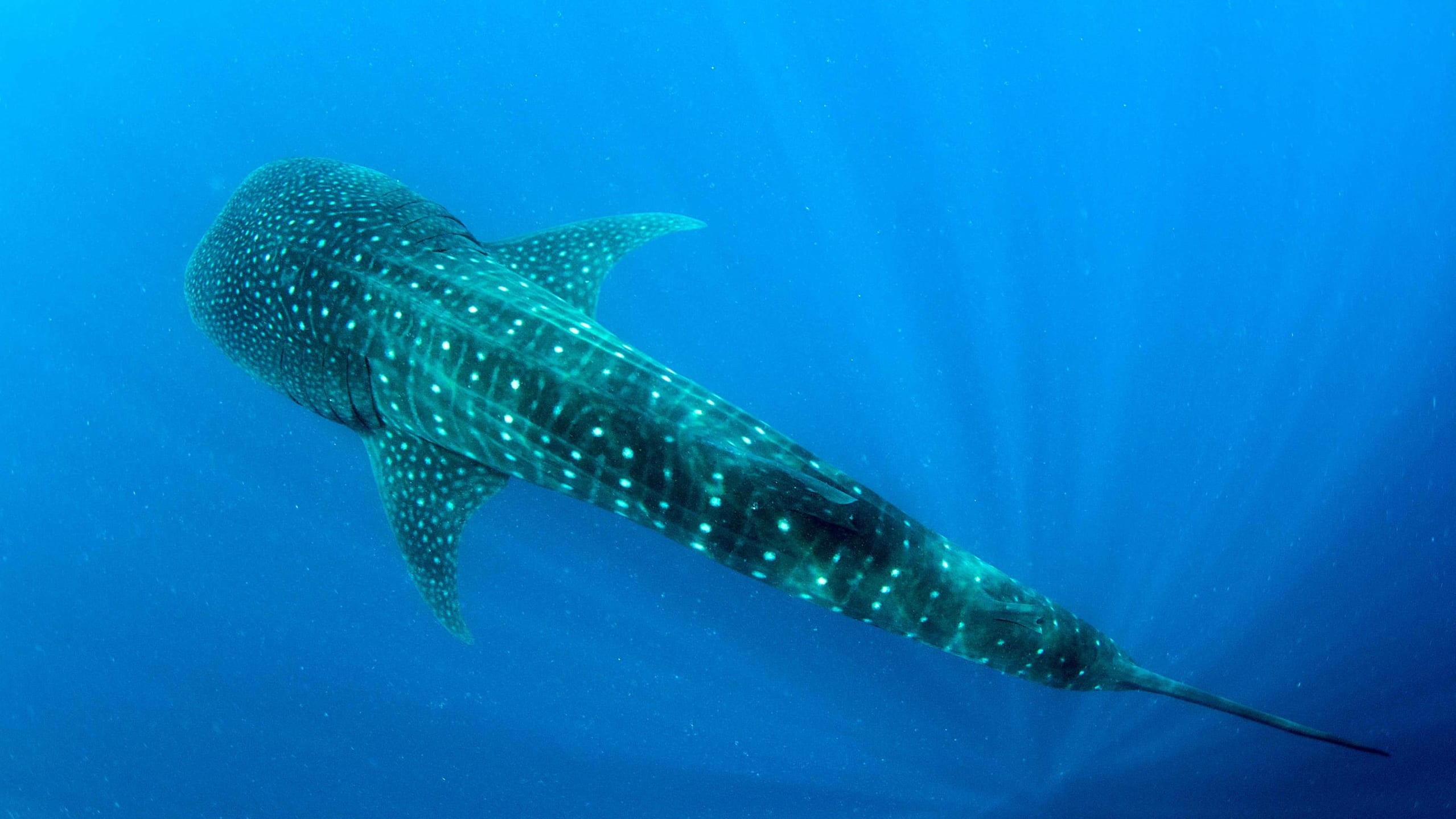

Cover Photo: Whale sharks are a perfect example of the diversity of sharks. Whale sharks are the largest fish on Earth, yet they feed on plankton, some of the smallest. Cover Photo: Umeed Mistry

Sharks were not always rare in the Andamans. From smaller species like reef sharks to larger open ocean predators like the tiger shark, the diversity of shallow and deep habitats has made the islands ideal for these cartilaginous beauties. Chronicles from 19th-century British and American expeditions offer us a glimpse of this. One reads phrases like “a great number of sharks swam about our vessel”, “it was the most enormous shark”, or even “shark catching is a principal amusement for the officers.” AR Brown’s 1922 paper on the tribes in the Great Andaman Island describes the use of Andodendron creepers as a waistbelt for protection when swimming in “shark-infested” waters.

Fast forward to a century later, in 2000, reef sharks, nurse sharks, and even bull sharks could be seen when diving around touristy Havelock. Where have these sharks gone? Marine biologist Zoya Tyabji and her team shed light on the status of sharks in the Andaman Islands in their 2020 study. Thirty-six species of sharks are known to inhabit the Andamans. Since the recreational shark fishing by the British two centuries ago and small-scale sustenance fishing by indigenous communities, shark fishing has become commercial. Sharks are caught as unintended bycatch (in scarily significant numbers) and from targeted shark fishing. An earlier study (Hornby et al. 2015) in the Andamans used fish catch data from over 60 years (1950-2010) to reconstruct how much of what was landed was sharks and rays. They estimate that 60,000 tonnes of sharks and rays were caught and landed in the Andamans in 2010 alone. This fits the larger picture of India being one of the top three countries worldwide to harvest sharks and rays. As of 2022, shark populations are in severe decline globally and very much so in India.

Back to the Minerva dive, on turning a corner, we saw a rock form an arch over the sand, creating the perfect cave. And there, before us, a beautiful six-foot nurse shark was resting, its head deep in the cave and tail gently bobbing near our awestruck faces.

What makes a shark a shark? What traits set it apart from other fish? Is it size? Razor-sharp teeth? There are about 500 species of sharks worldwide (~30 per cent in Indian waters). Great white sharks are massive apex predators that stalk the seas for large prey. But the biggest of all sharks (and fish), the whale shark, swims in search of microscopic plankton. Black-tip reef sharks may inhabit shallow lagoons while goblin sharks passively drift through deep seas. The smallest shark is around the length of a pencil (dwarf lantern shark), and yes, some sharks are vegetarians, preferring seagrass to flesh (bonnethead sharks). Like any animal group, sharks have adapted and diversified to suit the challenges of the habitats in which they evolved.

The mystical ways they sense the world around them add to the shark’s enigma. They have extremely sensitive noses. Finding prey in the vast ocean is easier when you can sniff out prey, especially secretions, hormones, or fluids from weak or injured animals. Admittedly this has snowballed into numerous myths about how far a shark can smell a single drop of blood. As far as we know, sharks can detect odours in very low concentrations from quite a distance. Numerically, at about one part per million from a few hundred metres away (not kilometres).

Many sharks also have excellent vision in low light. Mirrored crystals called “tapetum lucidum” line the back of their retinas reflecting incoming light back into the eye, increasing the detail they see when hunting at night.

However, their most bizarre ability, a sixth sense if you will, is detecting electric fields. Sharks (and rays) possess small pores on their heads connected via liquid-filled tubes to internal organs called the “ampullae of Lorenzini”. This allows them to detect electric signals (a heartbeat, for instance) even from hidden animals, helping them locate their prey with the precision.

A worldwide study in 2021 found that shark and ray populations have declined by 71 per cent since 1970. In the same time frame, there has been an 18-fold increase in fishing. Three-quarters of all sharks and rays are now threatened with extinction. Photos: Dhritiman Mukherjee (top left and above), Umeed Mistry (top right)

A subtle but useful adaptation is their dentition. Sharks have plenty of teeth, shaped to cater to a variety of diets and food textures depending on the species. These teeth are also an unending resource. Sharks are like evergreen trees in the way they shed and regrow worn-out teeth — not all at once, but in batches throughout their lives.

Sharks have invested in the slow, careful route when it comes to reproduction. Instead of producing lots of offspring in the hope that at least a few will survive, sharks produce only a handful of pups. With long gestation periods, pups spend a lot of time (few months to over a year) developing inside the female, growing much slower after birth and taking longer to reach sexual maturity compared to other fish. This gives them a higher chance of survival and longer lifespans. This strategy has helped sharks through millions of years of evolution but is, unfortunately, becoming a huge disadvantage since the onset of overfishing. Each year tonnes of individuals of different species, ages, and sizes are being overharvested by targeted fishing and as bycatch. With fewer adults left in the wild to reproduce and the extremely long periods sharks take to reach reproductive maturity, sharks cannot keep up with the rate at which they are being fished out.

Efforts are being made conservationists and policymakers across nations towards stemming this decline — increasing their protection status, stricter guidelines to reduce overfishing, and promoting shark tourism as a livelihood source instead of commercial fishing. In the meantime, what can we do? Sharks could use some good PR. It has been 47 years since the first of the shark-themed horror movies Jaws was first released, and sharks worldwide are still paying the price. Sharks have been known to attack people, but we must put this phenomenon in perspective to understand its scale. Of all shark species, three species that hunt large marine prey account for the majority of shark bites (white, tiger, and bull sharks), most often when people are surfing or body boarding in waters where these species occur. These have mostly been reported from parts of Australia, the USA, and South Africa. Using shark attack data from seven regions with the greatest number of shark attacks between 1970-2015, Midway et al. found that shark attacks averaged to less than one attack per million people per year. When there were more attacks, it went as high as five attacks per million people per year. All those internet memes about how you are more likely to be killed by a road accident, poisoning, or falling, still hold true!

Here is an exercise that can help increase our awareness and appreciation of sharks. Do a quick internet search for a list of sharks, pick a species that intrigues you and spend 15 minutes learning more about them. A hammerhead’s very wide eyes, or a catshark’s “mermaid’s purse”, or even the mysterious “cookie-cutter shark”! Getting to know these magnificent creatures will bowl you over, find a corner of empathy in your heart, and make you curious enough to see one for yourself.