Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

For months, an African big cat and a Central Indian forest have been making headlines in India. In September 2022, almost 70 years after the Asiatic cheetah went extinct in India, eight African cheetahs were released in Kuno National Park, Madhya Pradesh. The project has been widely celebrated as the world’s first intercontinental translocation. But was it?

Few of us know that 2022 is not the first time an African big cat has stepped foot in Kuno. There’s another unlikely link between Kuno and Africa — a story that goes back nearly 120 years.

The year was 1873. Colonel Hall had shot the last known specimen of an Asiatic lion from Central India, somewhere close to the town of Guna, about 200 km southwest of Gwalior city. Eleven years later, in 1884, Hughes-Buller, an officer of the Central India Horse, would report sighting a lion within Gwalior state’s borders. Natural historians and hunters thought this was the last they would ever hear of a lion in Central India. Gwalior, however, had other ideas.

In the winter of 1900, Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, was scheduled to visit the princely state of Junagadh in Saurashtra, where he hoped to bag a lion in Gir’s forests. By then, it was the only place in the world where he could have come across an Asiatic lion. However, when the plan was publicised, there was an outcry against it, given the already decreasing lion population.

(1) "My own conviction is...that one should take to this pursuit [tiger shooting] in a spirit of moderation, for excess of anything is harmful" – Madhav Rao Scindia in his book A Guide to Tiger Shooting (1920). (2) Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, posing with his wife and a hunted Bengal tiger, 1903. Photos: Carl Vandyk, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (1), The original uploader was Ernst Stavro Blofeld at English Wikipedia., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (2)

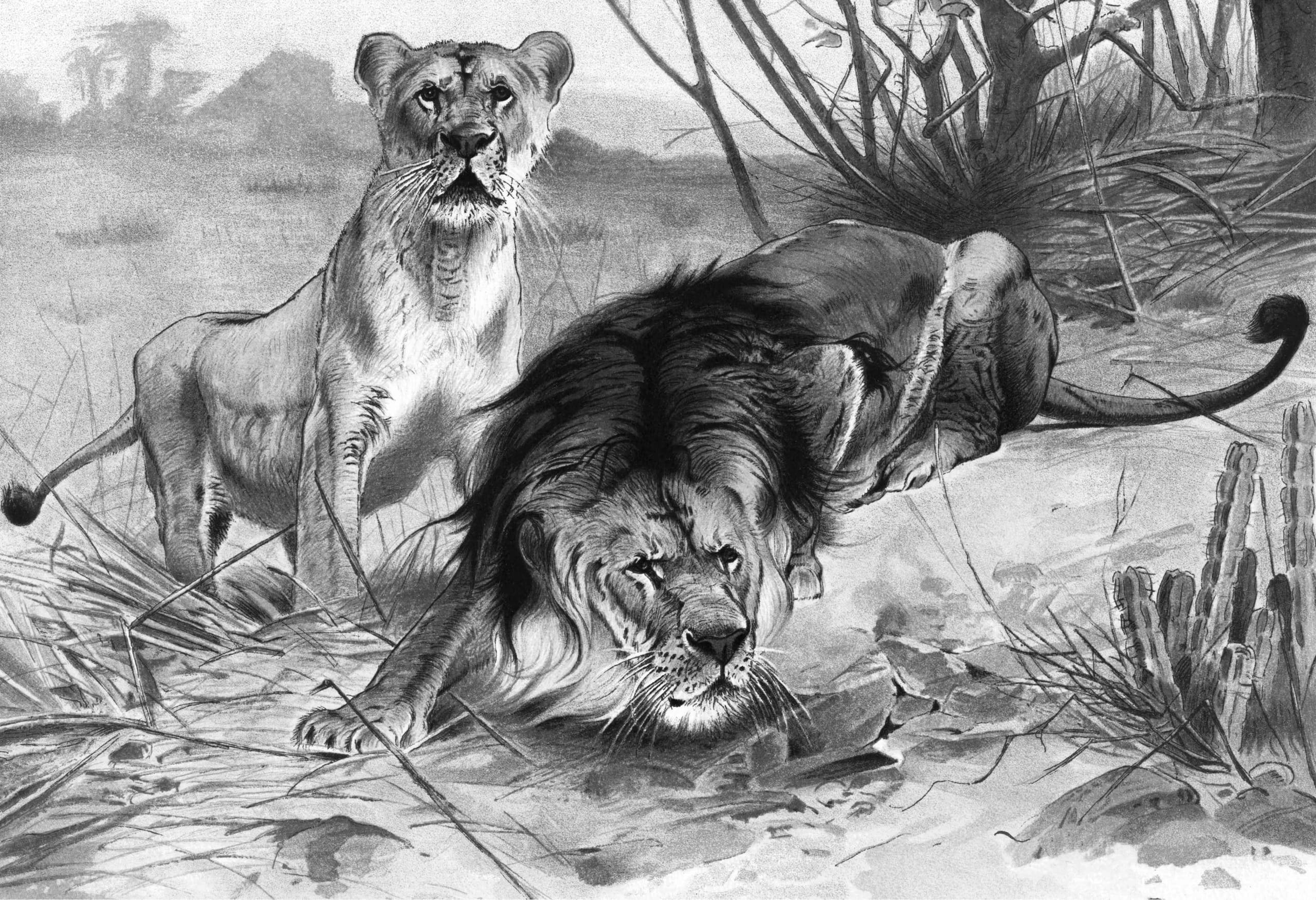

Cover Photo: “The local name of the lion is sawaj, and it is sometimes called the untia vagh, from its colour resembling that of a camel” – Lt. Col. L.L. Fenton on Gir’s lions in his book The Rifle in India (1923). Cover Photo: mikroman6/Getty Images

Curzon, therefore, abandoned his lion-shooting plans and set his eyes on the tigers of Gwalior instead. The princely state of Gwalior was famed as a favoured shooting ground for British dignitaries, especially because the Scindia rulers — keen tiger hunters themselves — regarded their tigers as social and political assets of the state.

While tiger shooting here, Curzon made a remarkable suggestion to the Maharaja of Gwalior, Sir Madhav Rao Scindia. He suggested that lions be reintroduced into Gwalior’s forests, promising all help through his good offices should Madhav Rao take up the idea. Scindia was convinced. Lions would return to Central India; lions would return to Gwalior.

The only possible source for lions in India, he knew, was Junagadh. In 1901, Madhav Rao had the British agent at Rajkot write a letter on his behalf to Junagadh, requesting eight lions from Gir. However, in a curious case of the past mirroring the present, just as Gujarat would steadfastly refuse to spare Gir’s lions to Kuno more than a century later, the Nawab of Junagadh turned down Gwalior’s request, arguing that there were too few lions to spare. A determined Madhav Rao turned to Africa, just as more than a century later, Gujarat’s refusals would make Madhya Pradesh look towards Africa.

With a little help from Curzon, ten young lions were captured from Africa. Some came from the East Africa Protectorate (Kenya), others reportedly from Sudan and British Somaliland. Arthur Blayney Percival, an officer with the Game Department of Kenya, in his book A Game Ranger’s Note Book (1924), provides a detailed account of procuring and raising three wild lion cubs for Gwalior before sending them to India. He also has a fascinating photograph of one of these cubs who eventually ended up in Gwalior’s forests.

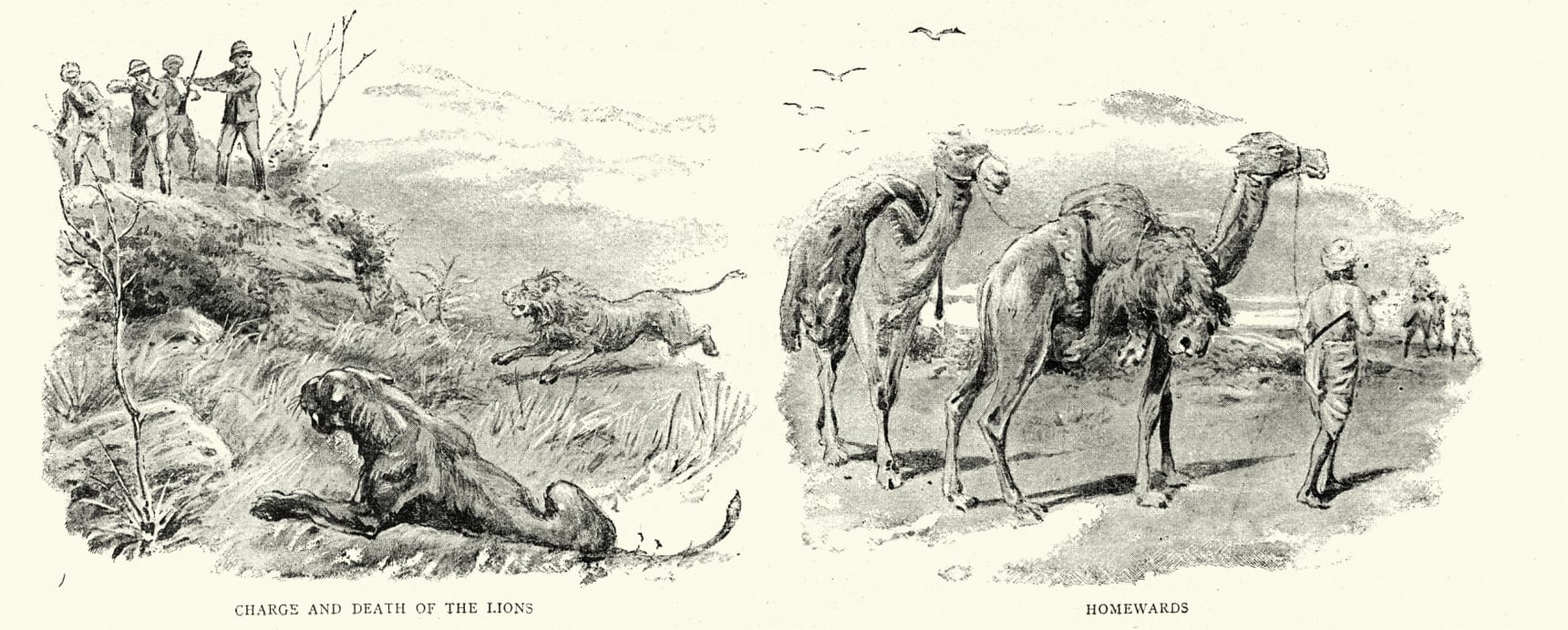

These African lions finally arrived in India in early 1906. After two years in captivity, two pairs were turned loose in Kuno’s forests. Another four were released in 1910. However, these lions soon turned man-eaters and reportedly killed 29 people. Madhav Rao instructed his head shikari, a Frenchman named Auret, to recapture the lions rather than shoot them.

The Gwalior Shikar Department devised a unique plan to follow Scindia’s orders. They pinned the lions down to the vicinity of the village where they had made their last kill and plastered innumerable extra-sticky flypapers across all the possible exit routes. As the lions tried escaping, the fly papers stuck to their feet. When they tried to scrape them off with their teeth, they ended up further plastering those flypapers onto their manes and faces. Eventually, they were covered in flypapers and could barely see. They were then netted and carted back to their former enclosures.

However, not all lions were accounted for. A few lions evaded capture and dispersed across the dry deciduous forests of the Kuno river valley, where, in all likelihood, they subsequently bred. No lions were released here between 1911 and 1920.

The most authentic account of the last phase of the Gwalior experiment comes from Colonel Kesri Singh, head of the Gwalior Shikar Department, in 1920. He was one of the most famous hunters of his era, claiming to have brought a thousand tigers to the gun. He wrote that by 1916 the captive African lions of Gwalior were being held in a stone-walled enclosure at Dobekund. Dobekund lies within present-day Kuno National Park, and the enclosure’s remains still survive. The lions at Dobekund were always provided with live buffaloes, so they retained and honed their natural instinct to kill live prey. This continued for four years. By 1920, these lions had bred, and there were a total of 12 in captivity.

In August 1920, once again, a pair was released into Kuno’s forests, and they promptly disappeared. Then a second pair was released. These two hung around Dobekund, leading to an interesting incident that Singh describes in some detail.

The forests of Sheopur and Shivpuri were fecund tiger habitats, and the forests around Dobekund were no different. Singh wrote that the roars of lions from their enclosures almost always attracted wild tigers, and the only thing that stood between these two big cats was the walls of the lion enclosure. However, after the lions were released, tigers and lions seemed to have had a face-off at least once. Though tigers and Asiatic lions have historically cohabited landscapes across central and northwest India, this account happens to be the only written record, to my knowledge, of a tiger and lion — even if an African specimen — getting into conflict in the wild.

On the release of the second lion pair, a tiger killed the male. “They found the male lion lying dead with his body badly mutilated, showing that he had been killed by a tiger. The lioness was not seen anywhere in the vicinity”, Singh wrote.

Over the next few months, six more lions were released in batches of two. But when it was time to release the last pair, marking the culmination of the grand experiment of almost 20 years, things did not go as planned. The last pair turned to the cattle of Kuno’s villages and eventually killed a man. For Singh, this was the final straw. He marched to the village and shot both the lions on the spot.

However, the remaining nine lions disappeared into the vast forests of Kuno. Over the next few years, Gwalior’s African lions travelled far and wide across this landscape.

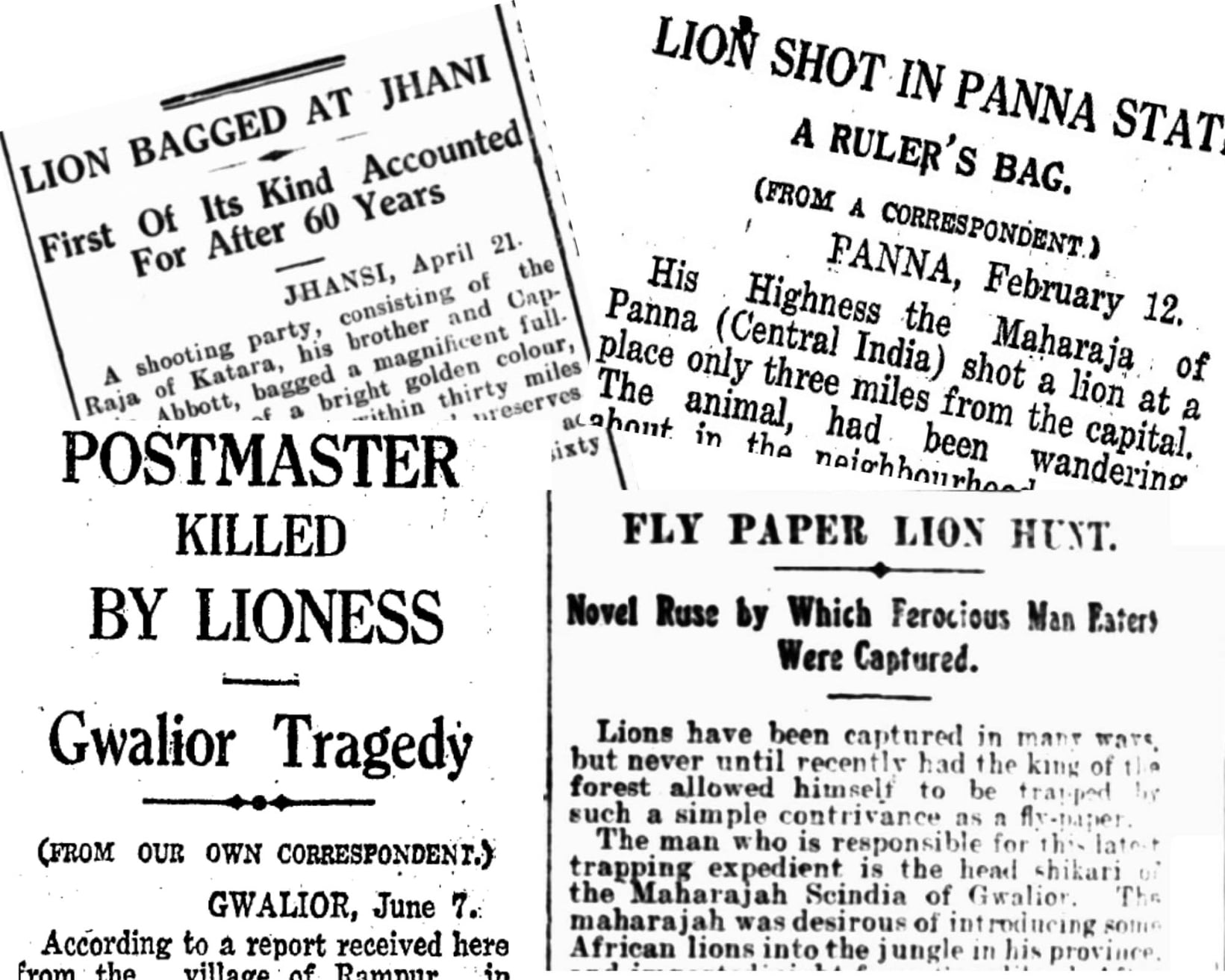

In 1922, the British resident to the Princely State of Kotah (now in Rajasthan) wrote of a lion being shot in Kotah, near the semi-deserted village of Shergarh, from where a lioness was also reported. He also noted that a lion was seen in the forests around Sawai Madhopur (now Ranthambore National Park) in 1921. Lions were frequently reported from Jhansi as well. A lioness with two cubs was reportedly seen around Jhansi in the early 1920s. In 1926, a lion was shot near Jhansi; another was killed in early 1928. Then, in late 1928 a mysterious man-eater — called the “yellow man-eater of Pachwara” — killed more than 20 people in the hinterland villages of Jhansi, earning a reward of Rs 500 on his head. However, he escaped the guns. A lion was reportedly shot again near Jhansi in 1930. Was this the Pachwara man-eater? Perhaps we will never know.

Elsewhere, a male lion was shot east of Gwalior State, in the princely state Panna (now Panna and Chhatarpur districts in Madhya Pradesh), by Maharaja Yadvendra Singh in 1927. A lion even moved into the United Provinces. In 1929, a lioness was reported from Etawah’s Fisher Forest, which incidentally today is the site of Etawah Lion Safari Park. Meanwhile, in 1930, the Holkar ruler of Indore state reported one lion wandering very close to his state’s borders. He was keen on capturing this male, importing a lioness, and initiating another lion introduction programme in his state. However, nothing came of it.

Lions wandered within Gwalior’s territory as well. In 1925, Maharawal Ranjitsinhji of Baria (now in Dahod district, Gujarat), while out hunting in Gwalior, claimed to have seen six lions; of which he shot one. A lioness killed a postman in 1933 at a village in Gwalior state. The last conclusive record of Gwalior’s African lions is of a lion shot at Jaronia by the Maharaja of Kotah on 17 May 1937.

All the above accounts almost conclusively establish that some African lions released between 1908 and 1920 bred in the wild. Reports of alleged lion sightings continued in this landscape right into the 1960s.

So this is the story of the world’s first intercontinental translocation project. But was Gwalior the first and last to conduct such experiments? What if I told you that in 1939, the King of Nepal decided to introduce lions in the terai forests of Chitwan? What happened to those “terai lions”? Well, that’s a story for another day.