Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Irrational fears and rational thoughts, both come from the same place—physically, the brain, and mentally, the mind. Between physiological processes (like the balance of hormones) that influence the brain and mental processes (like experiences) that shape our minds, there lies a delicately complex system inside our heads. Phobias are one of the many things that happen inside this system and while unrealistic by definition, they are very real for the people experiencing them. Most definitions of “phobia” explicitly highlight their irrational or unrealistic nature. In an article published in Harvard Health Publishing, Howard E LeWine defines a phobia as "a persistent, excessive, unrealistic fear of an object, person, animal, activity or situation. It is a type of anxiety disorder."

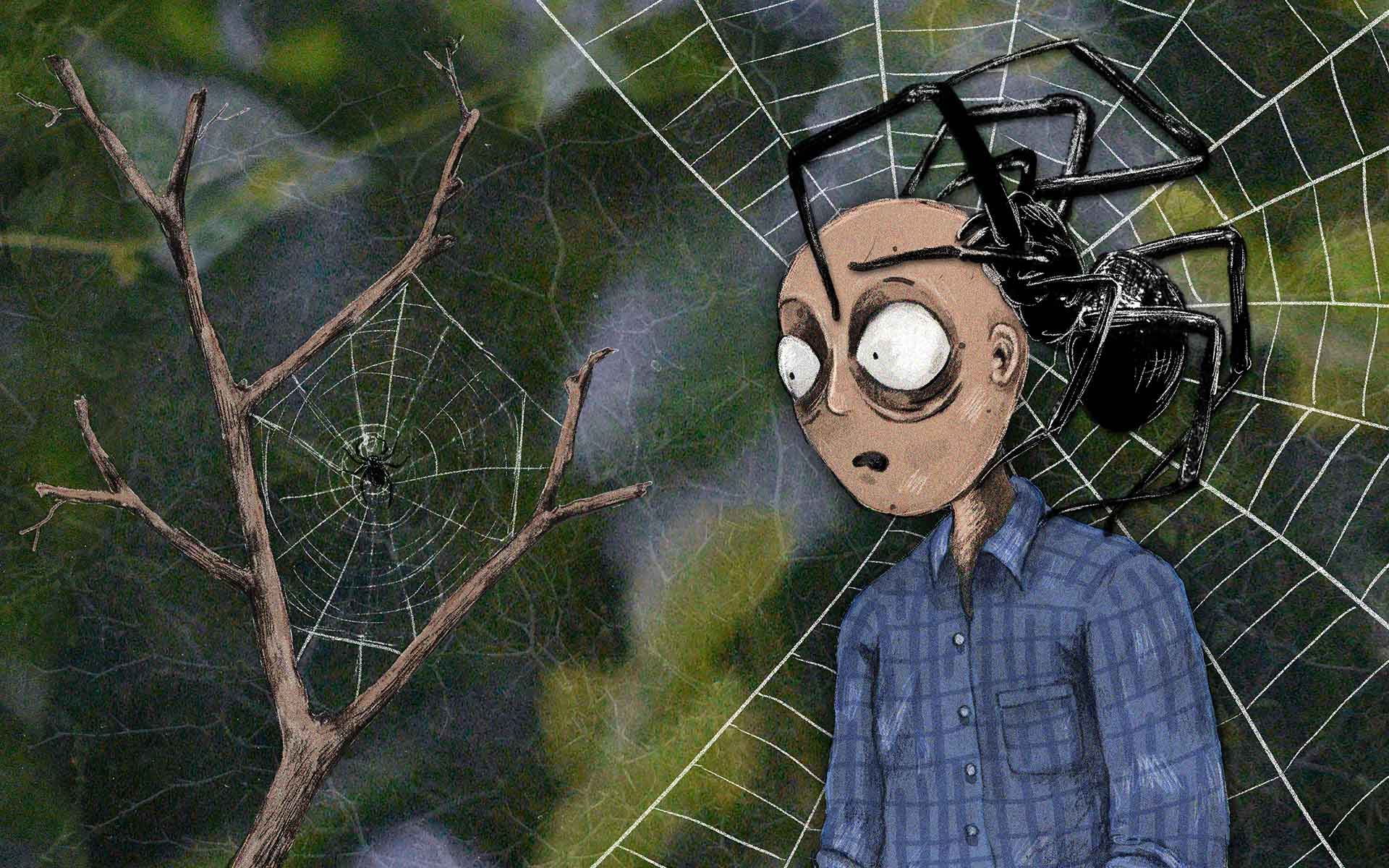

For instance, a person diagnosed with arachnophobia will experience severe anxiety at the sight of a tiny spider—an animal that is unlikely to pose physical harm to the person. The general discomfort with the idea of a spider is quite widespread among my urban social circles with word associations like “creepy” and “disgusting”. Many people who firmly believe they have arachnophobia remain reasonably calm around spiders. Despite their phobic claim, they exhibit signs of mild disgust and indifference at the idea of a spider—at least until we spot a colourful jumping spider that melts their hearts.

Have we always been creeped out by spiders? A quick look at indigenous art from around the world suggests otherwise. Indigenous communities in Australia painted sacred rocks with images of spiders on their webs. On the Gilbert Islands, “spider lord” Nareau is said to have created the universe. Great Andamanese tribes of the Andaman Islands share a similar belief in a spider creating the world. The Navajo of North America believe that a Spider Woman rescued humankind from its destructive origins and wove the land humans inhabit today. The Hopi community from the Southwest US believe a Spider Grandmother while weaving her web, thought the world into existence. Communities around this area also believe that a sacred Spider Woman taught humans how to weave. This association was also made across southern India, where traditional weaving communities were named Saliga/Saliya/Sali after the proto-Dravidian word “saali” which translates to spider. The Tamil epic Periya Puranam from the 12th century speaks of a spider devotee of Lord Shiva reborn as King Kochengan, a Chola king from somewhere between 600 BCE and 300 CE. Culturally, human communities across the world have shared a positive relationship with spiders for many millennia. This begs the question: Where, when, and how did we get tangled up in this level of dislike for spiders?

While cultures around the world had benevolent spider women and goddesses that created the sky, Medieval Europe had a different view of spiders. For starters, the old English name given to spiders was “attercoppe” (which translates to “poison head”). This represents the general mindset that prevailed across Europe through the Middle Ages — that spiders and their poison (likely intended as venom) could kill you. This is rather curious because there are no spiders in the United Kingdom or Europe that can cause significant harm to a human. One potential explanation for the spider's killer reputation in Europe could lie in the secondary bacterial infections that occurred around the area of a spider's bite. At a time when scientific reason and philosophical thought were meant to operate within the confines of the Christian Bible, it was likely simpler to park the blame on “poison head”. Medieval Europe was a place that saw widespread religious radicalisation, famine, and two full-blown plagues. As a result, communities had neither time nor inclination to form positive, empathetic relationships with the natural world. When this combined with the Christian narrative of humans having dominion over all other forms of life, Europe spent the better part of a millennium viewing the natural world as the human species versus everything else.

In a paper entitled "The "Disgusting" Spider: The Role of Disease and Illness in the Perpetuation of Fear of Spiders", Graham C L Davey observes "The development of the association between spiders and illness appears to be linked to the many devastating and inexplicable epidemics that struck Europe from the Middle Ages onwards when the spider was a suitable displaced target for the anxieties caused by these epidemics. Such factors suggest that the pervasive fear of spiders that is commonly found in many Western societies may have cultural rather than biological origins and may be restricted to Europeans and their descendants".

This culture of fear (of spiders) in the global west is evident in the psychological patterns prevalent across the United States. Between 3.5 to 6.1 per cent of the population is estimated to suffer from arachnophobia. This has prompted researchers in the United States to extensively investigate arachnophobia and its roots. Some studies on the matter have suggested that arachnophobia could be an evolutionary trait inherited from our ancestors who dealt with highly venomous spiders. However, these studies surveyed adults whose opinions and fears could easily have been shaped by experience and social learning (watching somebody else panic around spiders).

Recent studies on the subject have sought to mitigate this bias by looking for signs of arachnophobia in infants (six months old). The experiments for this study looked at pupil dilation in infants when they were shown images of snakes, spiders, and flowers. Pupil dilation in humans is understood to be a heightened sense of awareness — i.e., our pupils dilate when we are scared or excited. The results of these experiments showed that the infants' pupils dilated wider when they were shown pictures of snakes and spiders when compared to pictures of flowers.

In Western societies, the growing disconnect from the natural world also presented an excellent opportunity for Hollywood to monetise. The second half of the 19th century saw the growth of eco-horror films — a genre of cinema that demonises animals, creating characters with horrifying intentions and capabilities. As early as 1955, movies like Tarantula featured a 100-foot-tall spider terrorising people. Even as recently as 2015, Lavalantula presents giant fire-breathing spiders unleashed on Los Angeles.

India’s urban centres resemble the global west both with the “success” of capitalism and the growing disconnect with nature. People growing up in urban homes today, devoid of any natural space, find life forms like spiders and insects unfamiliar. With negative media and generational misunderstanding, we perpetuate a culture that replaces curiosity with fear. If this fear has gone as far as a phobia, then it is best dealt with by mental health professionals. However, if we are simply uncomfortable with unfamiliar life forms, we deprive ourselves and future generations of the joy of living in harmony with nature. My friends from urban centres still grapple with the idea of being comfortable around a spider. My friends from rural and forest communities, however, look at spiders just as they do any other creature (including their fellow humans) — with empathy. This empathy is rooted in the time spent understanding each other's role in our ecosystem. The spider inside your home evolved over 300 million years to eat tiny things and do little to no harm to humans. If we spend time in nature and learn to coexist with spiders, we may even be inspired by them.