Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Around the globe, the news is flooded with stories of wild animals reclaiming space, mainly in and around cities, as a result of the lockdown and human confinement precipitated by the Covid-19 pandemic. The Washington Post reported on 15th April 2020 that, “As humans stay indoors, wild animals take back what was once theirs”. The story chronicles how wild boars are roaming the streets of Barcelona, Spain, mountain goats are doing the same in Wales, UK, and Brazilian beaches have witnessed record numbers of hawksbill sea turtle hatchlings on deserted beaches. Similarly, Indian media has highlighted the spotting of nilgai, sambar, spotted deer, small Indian civet, leopards, and elephants on city roads. The coronavirus lockdown in India has also been perceived as a blessing in disguise for the Ganges river dolphin which have been spotted in several places due to a drastic reduction in river pollution.

Undoubtedly, the lockdown has made our air cleaner and river water clearer. It is the tranquil ambience and clean environment that has changed the behaviour of wild animals. Previously hesitant to explore spaces humans occupy, animals are now coming back to these places that were colonised from them decades or even centuries ago. In these altered spaces, until now most humans had not seen wild animals; they were strangers to them. The result was wild species lost in the mists of time in urban and semi-urban areas. Fortunately, the patches of natural environment that humans have created, in the shape of gardens, orchards, ponds, garbage dumps, or farms, provide animals with suboptimal refuge. Many generalist species that could adapt to these suboptimal spaces have modified their behaviour and survived alongside human beings.

Human dominated landscapes support a variety of animal species — birds being the most common. Snakes and small mammals like jackals, mongooses, squirrels, bats, macaques are all common to urban areas, though the diversity around rural areas is greater. Agricultural, horticultural, and fallow areas provide enough food and cover to many species of rodents, like porcupines and rats, as also hares, jungle cats, jackals, foxes, hyenas etc. Wild pigs, nilgais, and macaques thrive in many parts of rural India.

Wildlife sanctuaries and forests are the true storehouses of wild fauna, including predators like leopard and tigers, and large-bodied animals such as elephants, though they too show up in cities and villages on occasion.

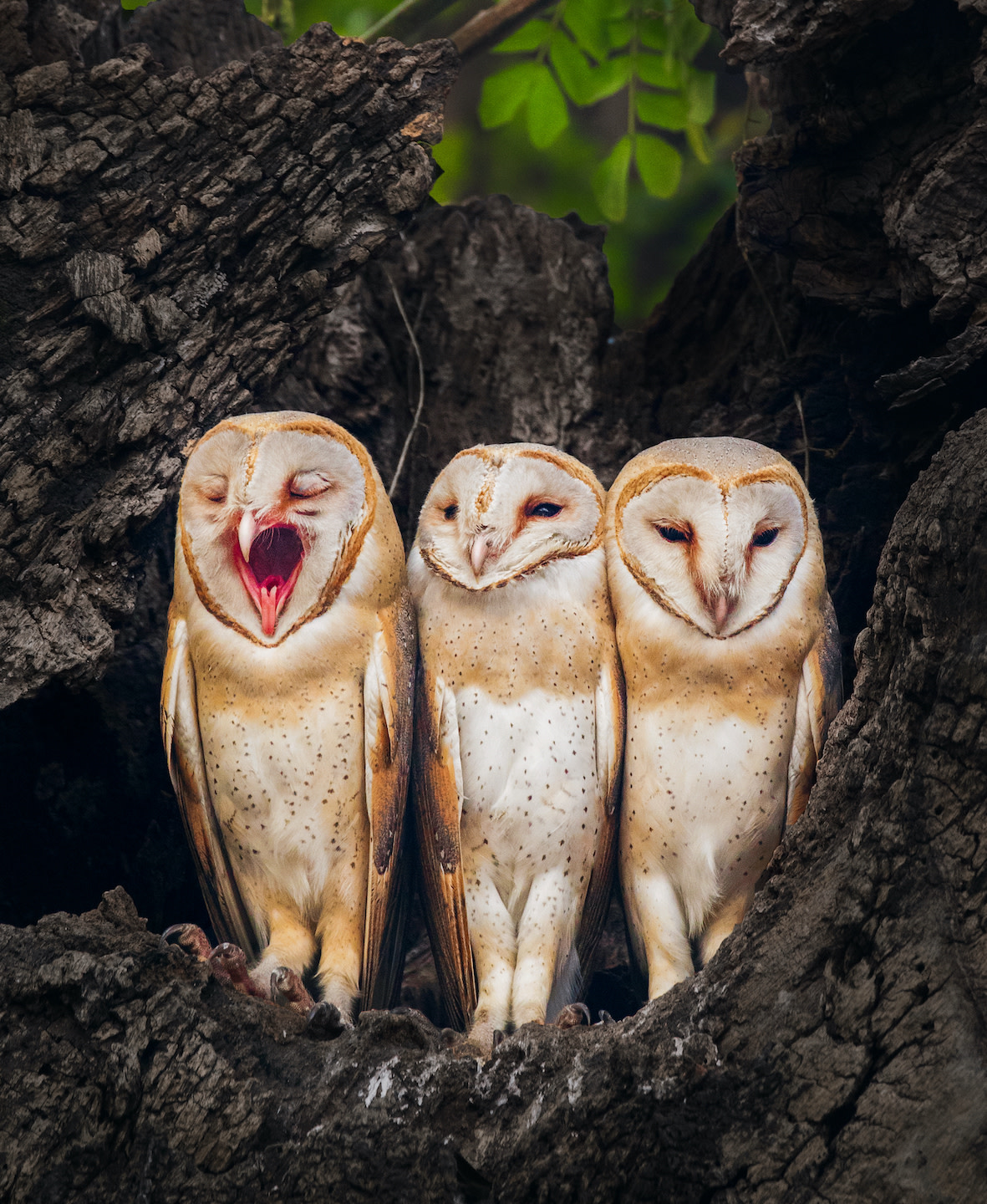

Cover photo: Since the lockdown, reports of wild creatures being spotted in cities have made headlines, but many have always shared our urban landscapes. For instance, barn owls, like this trio spotted on a fig tree in Kolkata, are common city residents. Cover photo: Sourav Mondal

By and large wild animals were not frequently detected in cities and towns before the forced silence generated by the spread of Covid–19. The key reason we are seeing more of them reclaiming human spaces is that animals are withdrawing the avoidance response to human beings. The response compels them to avoid human presence either by living away (spatial avoidance) or by staying away at certain times (temporal avoidance). These are risk minimising strategies of animals which let them coexist with humans. These adaptive strategies allow them to reduce the threat of predation, or the risk of being in conflict with humans. A 2018 study, by Kaitlyn M. Gaynor and associates published in the journal Science refers to humans as the diurnal apex “super-predator”, driving animals to temporal avoidance. Based on the observations on 62 mammal species the study established a strong effect humans have on the daily patterns and activities of wildlife.

For instance, human disturbance causes an increase in nocturnality of animals; this is highest in urban areas. Wild animals living close to human beings change their behaviour patterns and become more active at night, in order to maintain a safe distance from people.

The Covid-19 pandemic has drastically curtailed anthropogenic disturbance, creating much silence for animals in and around cities. This has allowed them to explore new spaces and look for resources for their survival, such as food, water, breeding sites, and protection. This has resulted in the sighting of more birds and mammals in cities. At the same time, people now have more time to observe their surroundings, which has also contributed to increased animal sightings. People of all age groups seem to be enjoying the viewings or news of the presence of wild animals in their vicinity. This reaction is positive and a must for the continued coexistence between humans and wildlife.

The silence and low disturbance levels in the countryside, especially adjoining wildlife-rich areas has created a different situation. Cases of wild animals like leopards, elephants, and bears coming out to human occupied areas have increased. These animals often venture into areas of human habitation in search of food, but now, with very little activity on, they are increasingly being noticed. As per media reports, wild animal-human conflict has gone up in Central India in April 2020. In Bihar’s Valmiki Tiger Reserve, authorities rescued four leopards sheltering in houses in villages close to the forest. One leopard from the same area travelled over 250 km along the river Gandak and was captured successfully. These are cases where the tranquillity has caused negative interactions between human and wildlife.

The key questions we must now ask are: How permanent are these events? Is it really going to help wildlife in the long-run? Clearly, the events are not going to be long-lasting, due to one obvious fact, that the situation will get back to square one once the ongoing crisis is over. And most importantly, animals will not find resources, especially in urban areas, to sustain their needs. For example: if a nilgai comes to Noida from the adjoining Yamuna floodplain, what will it eat in the concrete jungle? Ultimately it will have to go back.

There is another matter to consider. Wildlife sanctuaries and forest areas will also bear the brunt of the pandemic-driven economic slowdown. With increased loss of jobs, particularly among poor and vulnerable communities, people will turn to illegal extraction of forest resources to counter their livelihood challenges. This is sure to have a major impact on the quality of wildlife habitats and forest managers foresee a challenging situation.