Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

The ocean can be a big scary place for newborns. Luckily, marine parents have evolved a variety of strategies to help them cope. There are different parenting techniques starting with the nature of reproduction: whether fertilisation is internal or external. Internal fertilisation involves copulation, much like humans, and is the norm for all marine mammals and reptiles. These species provide the highest degree of parental care. External fertilisers aren’t as involved in their children’s lives, though they do give their young a storehouse of tools and knowledge, tightly packed into their genetic fabric. Here’s a look at why ocean parents are among the best in the world:

Extreme self-sacrifice

We often talk about lost sleep and failing selfcare regimes when raising a child. In the ocean, where there are no nannies, the sacrifice can range from a few days of not eating to complete starvation and death.

Whale mothers, for example, travel thousands of kilometres, away from their feeding grounds, to give birth in tropical waters. Clear tropical waters are devoid of whale food but are ideally warm for a blubber-less calf. Here the mother breast feeds her child but is unable to eat herself. Depending on the species, the lactation period can last anywhere from 4 to 11 months. The mother fattens up the calf for their journey back to temperate seas. During this time, the whale mother often grows increasingly weak, and can become an easy target for predatory sharks or orca pods.

Such sacrifice is not limited to the higher forms of life. Invertebrates care too. Octopus mothers lay fertilised eggs in their den, guard them, and aerate them for the entire duration of their development. Octopuses are programmed to reproduce once; the females invest all their energy in caring for their eggs and die around the time of hatching of the eggs.

Marine fathers demonstrate a high degree of sacrifice as well. Brooding seahorses not only carry the eggs in their brood pouch but also supply them with energy-rich fats and minerals. Some fathers, like cardinal fish and jaw fish brood eggs/young in their mouth. They safeguard the developing eggs in their mouth, temporarily suspending feeding activities to protect their offspring.

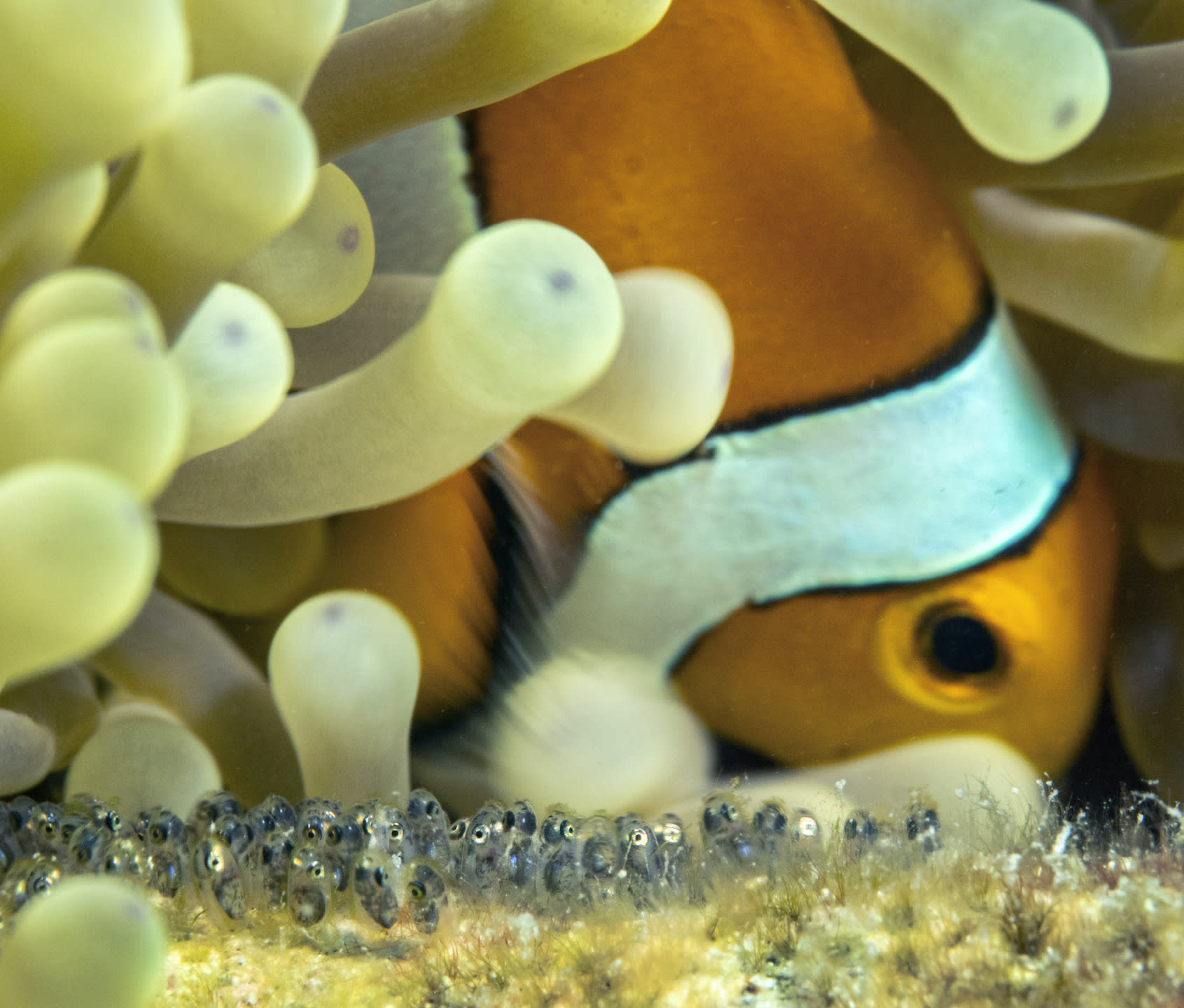

Cover: Clownfish eggs develop under multiple elevels of protective care. Besides the secure choice of a home, doting parents ensure the eggs are well aerated and free of debris, and fearlessly chase intruders off. Photos: Umeed Mistry

Attention to detail

Shark and sea turtle eggs are fertilised internally and cared for until the time they hatch. Most sharks give birth to live young in carefully identified safe areas or shark nurseries. Female sea turtles emerge on nesting beaches to lay their eggs, carefully and painstakingly dig holes, deposit their eggs, and cover them up before returning to sea. Some genius mothers also build “fake nests”, devoid of eggs, to trick and confuse predators.

Couple goals

In reef fish, pairing-up is a common way to ensure reproductive success. The brooders do it, so do some spawners and egg layers. Pairing with a good mate not only ensures high genetic quality of the offspring, but can also help share the burden of protection. In gobies, for example, the male helps guard the burrow where the externally fertilised eggs are developing, allowing the female to forage for prey. Clownfish pairs upgrade the family defence systems by laying their eggs next to their stinging anemone home, so in addition to the male and female guarding the eggs, the anemone also helps keep predators at bay.

Protective moms

The fiercest mothers need no assistance. If you regularly dive in the tropics, you may have experienced an attack by a moustache triggerfish mother. These triggerfish lay their eggs on the reef floor and guard the inverted cone-shaped space right above the nest. Unsuspecting divers are chased by these mothers when they accidentally enter their territory. My dive fins have many triggerfish bite marks from such interactions. Unfortunately, while the triggerfish is busy chasing away SCUBA divers, reef predators may chomp on her unguarded eggs.

Defence endowments

While all this care that parents take is rather admirable, most marine creatures are pelagic spawners, i.e. they release their eggs and sperm and hope for the best. It is a numbers game — they produce thousands, even millions of gametes, given the steep odds for survival. In these cases, the parents pack their kids with the necessary equipment to survive in the wild without parental care. Fish egg and larvae, for example, have generous yolk reserves to sustain themselves until they are able to feed independently.

Planktonic babies — the larvae of marine organisms that live on or near the ocean floor like coral, worms, crabs, lobsters, sea stars, urchins etc. — face pressures unfamiliar to their parents. The predators, the currents, and the constant churning is mind boggling. Their survival is based on the strategies that have evolved over hundreds of thousands of years. These babies have inbuilt buoyancy systems that help stabilise their position and orientation in the water column. They are also well endowed with defensive gear; spines or noxious compounds that make them undesirable to most predators.

In the late 1990s, a group of American researchers conducted a simple experiment to understand the morphological and chemical defences of marine planktonic larvae. Larvae were offered to common fish and invertebrate predators, and if rejected they were ground up and offered again. Predators ate snail, barnacle, crab, and mantis shrimp larvae but only in the ground up form, while certain larvae like those of worms, sea stars and corals were not consumed whole or ground up. The study was able to distinguish between larvae that rely on armour for defenses and those that are inherently unpalatable. Marine larvae might look cute and have cute sounding names like zoea (crab larvae) or planula (coral larvae), but they are mother natures’ mean survival machines.

Community care and cultural values

Even after the settlement stage, some young ones get the support of their communities. Sea urchin adults often safeguard baby urchins underneath their spines. Land crab juveniles take refuge in adult burrows, feeding on scraps left behind by the elders. And when community support is not obvious, juveniles are instilled with the right values to make the right decisions. For example, coral planula larvae are programmed to settle in crevices out of the reach of predators, where they can grow and slowly develop their hard bodies to face the big blue world.

For the layperson, successfully raising a child to adulthood is a source of immense pride. But in evolutionary terms, it defines the individual’s fitness. For all animal species, it’s not just about being a good dad or a good mom, it is driven by a biological need to ensure propagation of one’s own genetic code.