Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Next came the second nerve-racking part of the hunt: I had to find the sedated tiger quickly. The sooner we found him, the safer he would be from any chance encounter with another tiger or a bull elephant.

By now the capture team reassembled around me. Ranger Chinnappa, standing at six feet, five inches tall, towered over everyone. He was from the local Kodava warrior caste, and was eight years older than I. Chinnappa had schooled me in jungle craft in the years since we first met two decades earlier. We found we shared a passion for saving wildlife, not hunting it, which was the social norm those days. Over the years, we developed a deep bond of friendship. With us were two more men from the same warrior caste: forest guard Subbayya, a well-built, mustachioed former soldier in his forties, who was Chin nappa's able deputy; and the veterinarian Nanjappa, a professionally competent, compact man in his thirties.

The rest of the team was comprised of the two elephant mahouts (drivers) and a dozen trackers. All were skinny, unimpressive-looking men from the local Jenu Kuruba (honey gatherer) tribe. Their darker complexion, curly hair, and unique facial features indicated their earlier and stronger links to original migrants from Africa, the first humans to colonize the Indian subcontinent seventy thousand years ago. These tribesmen were masters of jungle craft.

Our team of tiger catchers was all male, except for the two beautiful female elephants. Unlike the men, these stately ladies would not flinch even while facing a wild tiger at close range. They were really the linchpins of this tiger beat.

I had posted Raju, the best among the spoor-trackers, as a scout on a tall Terminalia tree about one hundred meters down the trail from where I had darted the tiger. From his much higher perch, Raju looked out for the tiger after it was darted, and picked up its spoor. The rest of us followed him, fanned out in a semicircle. Behind us came the elephants with their mahouts, also scanning the jungle ahead of us for the tiger.

In late January, the earth was parched and the dry leaves littered the forest floor. Untrained eyes could never detect tiger spoor here. But Chinnappa and these hawk-eyed tribesmen could pick up minute clues-overturned leaves, grass pressed down by the passage of a heavy animal, or the faintest impression of a single toe. Tracking tiger spoor is an art, rather than a science. I was pretty good at it, but no match for these true masters.

From my scientific training, I was aware that within a few minutes the sedative would begin to paralyze the cat's hindquarters. Thereafter, tracking its spoor as it dragged its hind feet would be easier. Within ten minutes, muscles of the tiger's forequarter would also become immobile, compelling it to lie down, reluctantly. How far the tiger was able to go depended on its weight, physical condition, and the amount of drug injected. The farther it moved, the harder it would be to find. Beyond a few hundred meters, finding spoor would be nearly impossible.

After fifteen nerve-racking minutes, an eerie yell ahead startled me: it was tracker Raju. My heart skipped a beat, and then his words sank in: "Huli sikthu, saar!" ("I have found the tiger, sir!") The English honorific "sir" phonetically degenerates into a saar as it rolls off the tongues of the Kannada speakers in southern India.

A great weight lifted off my shoulders as I raced forward.

Raju told me how he had seen the big male tiger cross the dirt road, barely fifty meters from where I darted it. Raju was now in full flow: "I leaped down from the tree like a langur monkey, Saar, to dash after the tiger. He was walking all wobbly, like a drunkard returning home from the arrack shop," and added, "I followed him sir, barely an arm's length behind, totally fearless. I know you have injected him with the most powerful drug in the world, and he would do me no harm." These seemed like the words of a brave man.

I cracked a smile, and reminded Raju and other tribesmen of the events that unfolded three weeks earlier, after I had darted my very first tiger, Mudka. That was the first tranquilized tiger these men had ever laid their eyes on. When we found it, it lay on its flank, its massive chest muscles heaving as it breathed. It occasionally twitched its ears, and, most ominously, its cruel yellow eyes were wide open.

Only four of us had approached the fallen tiger: Mel Sunquist (my collaborator at the Univeristy of Florida), Ranger Chinnappa, Guard Subbayya, and me. The trackers had stood twenty meters away, watching us in alarm. We of course knew the tiger was temporarily harmless because of the loss of muscle control induced by the sedative. To these jungle trackers, however, the tiger seemed menacingly awake, and our actions entirely suicidal.

After much coaxing, the tribesmen had, one by one, inched forward to gather around the tiger. They hesitantly joined me to assist in measuring the tiger's body dimensions with a tape.

Then the tiger moved its head head ever so slightly, and it was like throwing a firecracker at a flock of feeding pigeons. The tight cluster of tribesmen around me exploded. They dashed off helter-skelter, seeking the safety of any nearby tree. Five of them, led by Raju, clambered up a pole-sized sapling of Phyllanthus with the agility of langur monkeys. Unable to bear their combined weight, the sapling had bent earthward, forming a graceful arch. The terror stricken men hung on for dear life, their feet just inches off the ground. With their glittering black eyes and skinny frames, the diminutive men strung along the bough tightly looked like giant fruit bats clad in khaki shorts. My peals of laughter had not helped. It took much coaxing for them to resume work.

Now, I teased Raju about his bravery in the presence of that tiger. Everyone joined in the laughter. Finding this tiger had released our bottled-up tensions. Although we had a lot to do, my team was ready to work with clockwork precision.

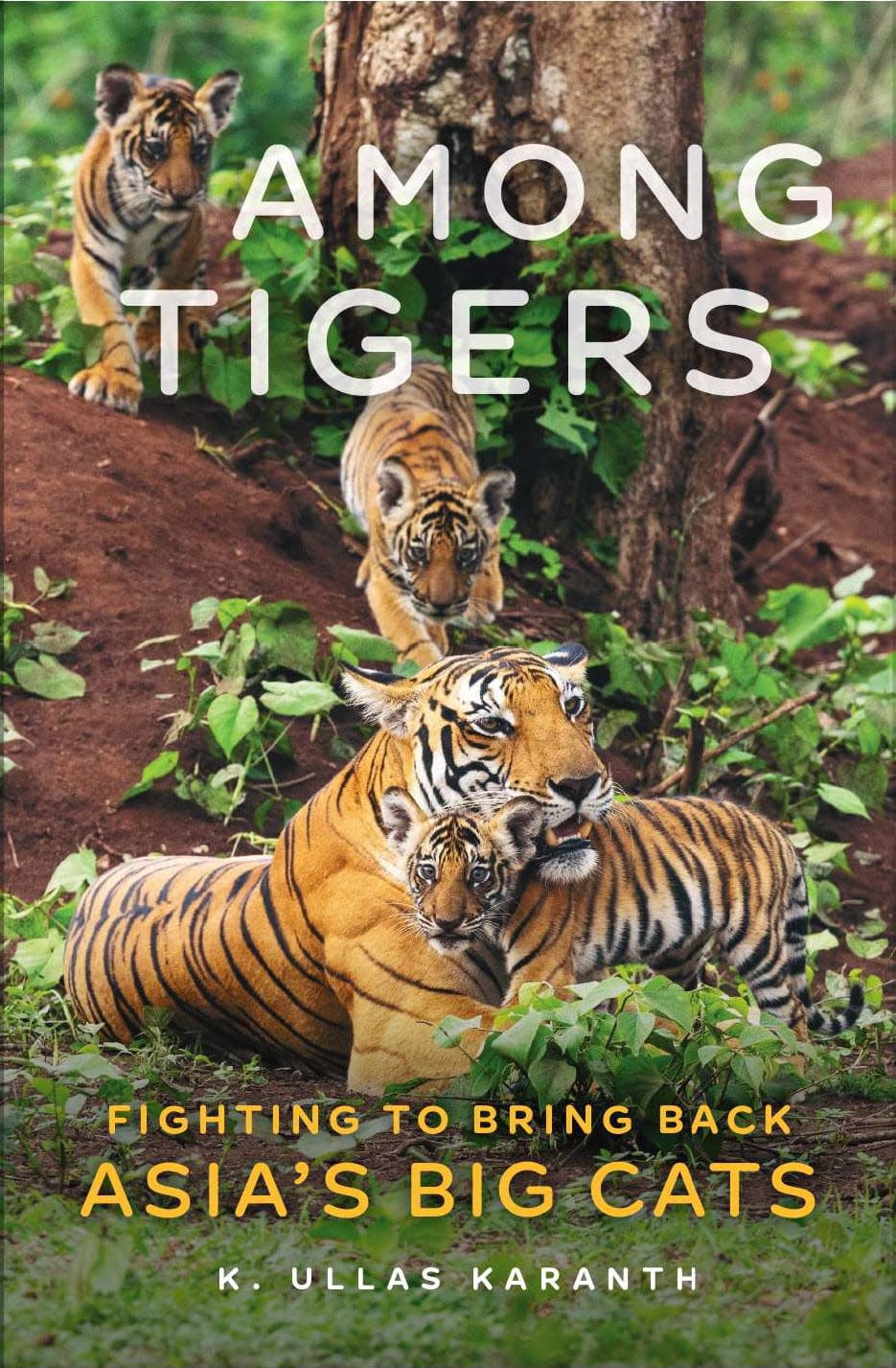

Excerpted with permission from Among Tigers: Fighting to Bring Back Asia's Big Cats by K Ullas Karanth. Published by Chicago Review Press.