Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Across the world, 48 football fields are lost to deforestation every minute. The forests around Eaglenest seemed destined to be mowed down for the promotion of football and other sports in India’s capital city. From around 1980, there was a surge in the commercial demand for timber from Arunachal, fueled mostly by the 9th Asian Games that were to be held in New Delhi in 1982. Timber operations occurred on a much smaller scale prior to that, to meet just house-building and firewood needs. With the Asian Games that opened up the flood gates for the commercial demand for timber, plantation and afforestation measures paled in meeting the demand. Indi Glow remembers that three quintals of Khasi pine (Pinus kesiya) seeds were aerially sprayed in the forests around Singchung and Tenga in 1981.

Then there were smaller patches (35-75 hectares) (now in Ramalingam and the helipad area) of blue pine (Pinus wallichiana) and chir pine (Pinus roxburghii) plantations.

So what was logging like? There are no reliable estimates of numbers—though we tried getting some. “Kya ginti karega—ek hazar se bhi jyada tha? (what will you count—there were more than a thousand people between Shergaon and Ramalingam area)”. There were enough explanations about the scale and intensity. “Jungle bharke aadmi (the forests were full with people)”, was how our conversations moved to getting more details. A contractor could have up to 100 people working under him. Around 70-150 people worked as loggers just around Sharua (the Bugun name) for the area around Lama Camp. Over a wider area (from Signal to the top of Thungree village), the logging workforce had roughly 500-600 people.

Life was not easy—people pulled logs (called dhulai in Nepali) with a chain and hook strapped across their shoulders. They pulled logs alone in tough mountainous terrain, from as far as five kilometres inside the forest, until they reached a path which was better connected. With age, their back-breaking work took its toll and left many with back and knee problems. Many paths that exist in the forest today are actually old logging trails or roads where 1-tonne trucks carried logs back to the depots. These trucks made multiple trips back and forth (to and from the depot). On a few trips they got rations for staff that were stationed at logging camps inside the forest. The amount was deducted from their salaries.

They were paid approximately 150-200 INR a day, based on the cubic feet of wood they processed. They were paid monthly or sometimes slightly later; women often said they didn’t know how much their husbands earned. Given the lack of money that came home, they ran their homes by making and selling distilled rice wine. Ironically, drinking seemed to be the very reason that money didn’t make it to their own homes.

What they called homes or logging camps were basic—tarpaulins for roofs and wood planks for walls. It was where Bishnu Maya raised Som Maya—her 9 month old infant. She feared for her family’s safety, especially because the Sharuwa Lyap/Lama Camp5 area had many Asian black bears. But all is well with Som Maya, who has settled in the nearest village from Sharuwa Lyap/Lama Camp area, and now has five children. Her eldest daughter is 18 years old.

She has more permanent neighbours now; growing up was markedly different. Many people from the logging workforce stayed for two to three months at a place and then moved on to other logging camps. Some areas inside Eaglenest were hostile to camping, especially around Chaku, as there were no water sources, and hence remained free of logging. Other places such as Jigaon, Thungree, Chillipam and Shergaon were very conducive for logging operations. This was a period that lacked chain saws and tree girths reached almost epic proportions—it took many days to cut down a single tree.

So what else changed with time apart from neighbours? Chamu Rai, who was part of the logging workforce for more than a decade, came to live in Alubari in 1994. Below Alubari they cut ootis (Alnus nipalensis), chiloni (Schima wallichi) and chaap (Michelia champaca). The forests above Alubari were good for chir pine and dhupi (Cupressus torulosa). There were 13-14 temporary houses in the area, mostly belonging to people involved in logging. The hill across Alubari had 5-6 houses where people engaged in a bit of agriculture. The number of people here dwindled as the Supreme Court passed an order in 1996 banning logging. It was the same year that Chamu Rai was mauled by a bear and got married. He jokes that maybe his wife liked his stitched-up face better.

Chamu Rai and the forests he lives in have scars that are mild but memories that are strong. Today in Alubari, Chamu Rai’s is the only house. He walks these forests now as part of the nature-based tourism set up around Sharuwa Lyap/Lama Camp. The touristic activities set up here are tailored around the spectacular discovery of the Bugun Liocichla. The Bugun liocichla was described between the community forests of Alubari and Sharuwa Lyap/Lama Camp in 2006. Dr. Ramana Athreya’s discovery has been extremely exciting—the Bugun liocichla was the first bird species to be described after India’s independence.

As interesting, linguistically, is that the discovery of this bird has given a loanword to English, which may make Bugun the only language in this region to have done so.

As the nature-based tourism tents dot the horizon, the logging camps are now history. The more recent visitors to the area are tourists from all over the world who come to see the liocichla, purple cochoa, honey guide and Ward’s trogon. Right now, there is a growing list of rediscoveries and range extensions from the Sharuwa area that includes the Abor Hills agama and Jerdon’s red-spotted pit viper, and butterflies like the Ludlow’s Bhutan glory and Tibetan brimstone. The Sharuwa area also has a larger cultural significance to the Buguns, as they consider it to be a holy mountain. They have declared this area as a Community Reserve. Their forests have seen timber contractors being converted into forest protectors.

There is a walk to remember this history. ‘Tragopanda’ is an old logging trail which is three kilometers long and once had 1-tonne trucks going back and forth. Today, tourists walk through these beautifully regenerating temperate broad-leaved forests to reach a mystical mountain lake (~ one hectare in size). ‘Tragopanda’ is a portmanteau of ‘tragopan’ and ‘panda’, as it is one of the best places for tourists to sight the Temminck’s tragopan (Bugun name: aabaub) and the Red Panda (Bugun name: samamp). In a happy turn of events, the forests now belong to the Buguns and the spectacular faunal and floral species that live there. The events of the Asian Games in 1982 were not game, set and match for these forests.

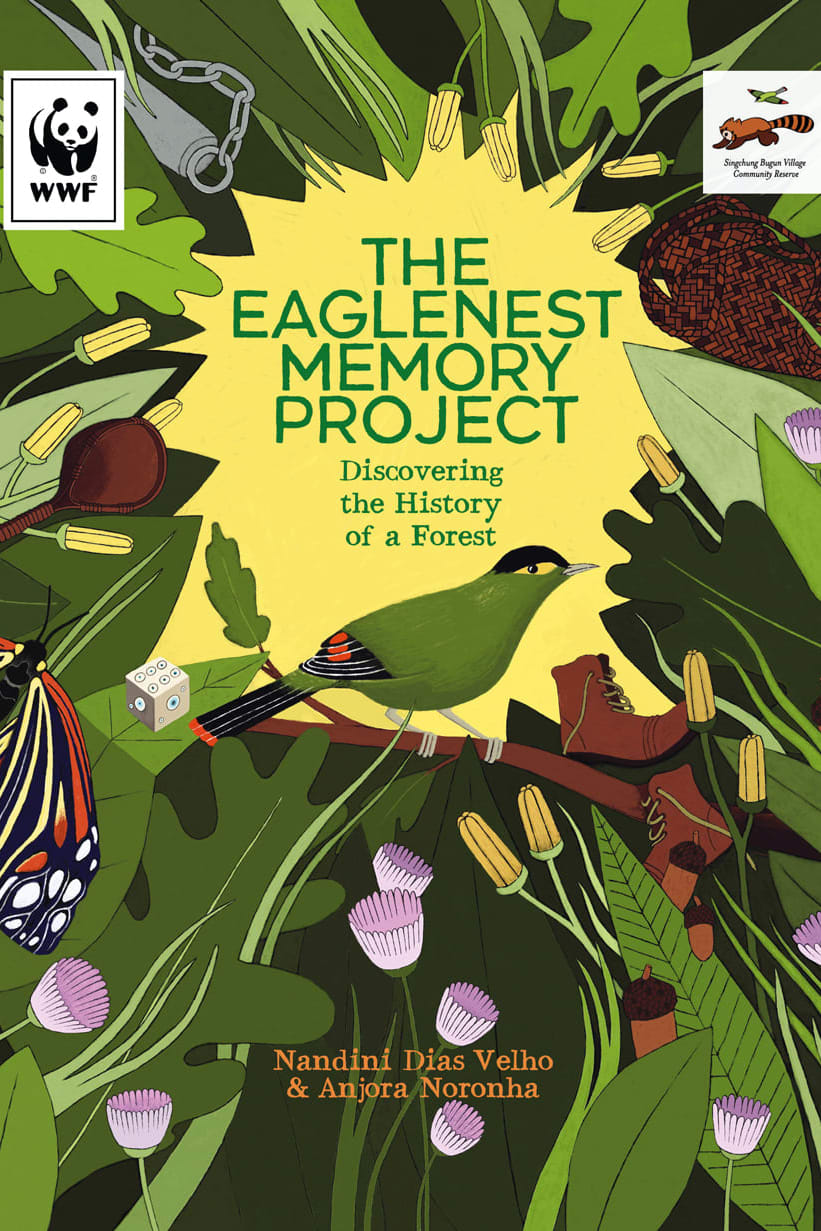

Excerpted with permission from The Eaglenest Memory Project by Nandini Dias Velho and Anjora Noronha, published by WWF-India, Price: Rs 695.00