Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

On a rainy day, we cautiously walk along a muck-ridden path to step into our guide, Milo Heshi’s home — a quaint bamboo hut with a fruiting orange tree in its front yard and at least fifty animal skulls hanging above the door. “I first started hunting with my father when I was 20,” Heshi says as he takes us through his collection. “I have killed two leopards, two sloth bears, 28 deer and countless birds and monkeys.” Heshi, 65, was something of a star hunter in Jessami, a Manipuri village along the India-Myanmar border. He is a member of the Chakhesang tribe, a Naga warrior community known for their hunting skills and traditions. Tied with twine and copper wire, the skulls are the hunting trophies he has collected and preserved over 40 years. “But this is my past,” he adds. “I haven’t hunted for at least a decade now.” With changing times, Heshi’s relationship with the forest has also changed. These days, he has a new career — helping tourists, wildlife photographers, and scientists spot the handsome and rare Mrs Hume’s pheasant or bar-tailed pheasant (Syrmaticus humiae) in Jessami’s forests.

Jessami, a remote village of 4,000-odd people, lies in the Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot, one of the world’s biologically richest and most threatened regions. In India, the hotspot includes parts of Assam, Nagaland, Mizoram, and Manipur and is home to diverse temperate and evergreen rainforests, rich wildlife, and several tribal communities. Like the Chakhesangs, for many communities, hunting is central to their traditions and beliefs. In Jessami, one of the most important annual celebrations is Tekru-nge, a 10-day festival dedicated to the sanctification of residents, and ceremonies centred around the purification of the village. Traditionally, until about a decade ago, on the second day of the festival, young boys who were a part of the sanctification ceremonies joined senior male members of the village on a hunt. About 100-200 male members of the village feasted on a large meal and set out for the jungle to hunt with catapults and sticks. Next morning, when they returned, the hunted creatures were hung on tall bamboo poles in the village square. The hunters with the largest number of animals were considered the strongest. The killings were also said to bring good luck to the hunters.

Cover photo: The stunning Mrs Hume’s pheasant is endemic to the dense forests of northeast India, Myanmar, Thailand, and southern China. It is the state bird of Mizoram and Manipur.

Hunting in Northeast India

The practice of hunting in the Northeast region of India goes beyond the need for consumption and livelihoods. Ambika Aiyadurai, in her book Tigers Are Our Brothers, says that hunting is threaded into social lives and beliefs. However, hunting has taken a toll on the region’s biodiversity over the last few decades. Guns have replaced catapults and sticks, making hunting easy and increasing the number of animals killed. Illegal trade has created a demand for wild meat and body parts, encouraging former traditional hunters to cater to the market. On the other hand, forests are being hacked for unchecked development and roads and for kiwi fruit, coffee, and palm oil plantations. Between 2001 and 2021, the Northeast lost around 4,350 sq. km of primary forest area, according to Global Forest Watch. Manipur alone has suffered the degradation of 460 sq. km of primary forests.

If habitat loss continues at this alarming rate and hunting practices are not curbed, it will only worsen an already imperilled biodiversity. "If hunting continues, we might experience the 'Empty Forest Syndrome' where a forest, which at first glance looks green and rich, is devoid of animals or birds since they have all been hunted. Some of our forests are already experiencing it,” says conservation biologist Shashank Dalvi.

A Ray of Hope

Jessami, fortunately, has reason to hope. In 2021, Nizote Mekrisuh, Chairman of the Jessami Village Council, stumbled upon an article in a local newspaper on the threatened Mrs Hume’s pheasant, the state bird of Manipur. The story spoke of how the bird was disappearing from the state and was declared “Near Threatened” by IUCN. Nizote had seen the bird in neighbouring forests and knew village elders who had grown up hunting it and decorating their headgear with its feathers during festivities. In Jessami, they called it tsara. An enterprising man with ambitions for his remote village, Nizote hoped he could use the bird to draw attention to his village. He found a willing ally in Weyepe N Mekrisuh, 34, PhD student of geology at Imphal University, and son of a former village headman. “When I spoke to my friends in Imphal and Delhi, I heard that people travel to Bhutan and trek for three days just to spot the tsara, and here it was in our backyards!” says Weyepe.

Mrs Hume’s Pheasant

Mrs Hume’s pheasant is an enigma and a photographer’s dream. In India, it is found in mountainous regions of Manipur, Mizoram, and Nagaland. The male is dashing with a long, banded tail. Its stout chestnut body has a shiny, steel-blue neck and a striking red eye-patch resembling a vermillion Zoro mask.

Unfortunately, the bird is disappearing across its range because of its diminishing habitat. Nizote and Wyeyepe realised how precious the bird was. The village council had already banned hunting of all animals in Jessami since 2018. They gathered all the elders over age 50 and sought their cooperation in spotting the bird. Weyepe called his friends in the media, and soon, news articles declared the bird’s presence in Jessami, attracting birders and wildlife photographers. When wildlife photographer Dhritiman Mukherjee heard from a friend that former hunters of Jessami were using their tracking skills to spot birds, he planned a trip there.

Photographing the Hume’s Pheasant

Although Mukherjee has been a professional wildlife photographer for over three decades, he had never seen or photographed the Hume’s pheasant. He arrived in Jessami in March 2022. Jessami’s forests, which lie on customary ancestral land owned by the Village Council, are about 15 km away. One windy evening, guided by Heshi and others, he set off with great anticipation.

In birder-speak, the pheasant is a “skulker” — one that hides in vegetation. It is almost impossible to spot in the daytime. However, at night, it roosts on tree branches. The village elders know where it lives, what it eats and where to find it. To track the bird, they search for trails of white droppings on branches and the floor. In a pitch-dark patch of the forest, Heshi finds droppings and then, almost immediately, a male gracefully perched amidst the crisscrossing branches of an alder tree. A buff-coloured female with a short, white-tipped tail was close by. Mukherjee finally gets his first image of the elusive pheasant.

“I was happy to get my first photograph, but then I wondered if I could see the bird in daylight without disturbing it at night,” he says. Nipewe Mekrisuh had seen the bird drinking water from a shallow pond in the forest. On a whim, Mukherjee set up a camera trap right beside it. The next day, its footage showed four to five individuals casually walking past the pond in broad daylight. “I wasn’t expecting so many! We could build a hide near the pond, where tourists could come and easily spot the bird. There would be no need to disturb it at night, and sightings would become easier,” he said.

That week, at a village council meeting, Weyepe, Nizote, and Mukherjee proposed the idea of turning this community-owned forest into a reserve where former hunters like Heshi could guide tourists and photographers. The reserve, under the care of the Jessami Village Council, could safeguard the diminishing population of the indigenous and exquisite Mrs Hume’s pheasant while simultaneously nurturing its natural habitat. “If this is successful, it could save the bird and the forest, and help the village build a sustainable tourism model that could be an example for other villages in Manipur,” said Mukherjee.

Similar stories of transformation have taken flight in other parts of the Northeast. For instance, until 2015, thousands of migratory Amur falcons were hunted in the Pangti village of Nagaland. However, the initiative of a few locals and conservationists turned the crisis into one of India’s most inspiring conservation stories. Former falcon hunters have now turned into guardians of the birds and celebrate their arrival every winter through a joyous public festival. Tourists flock to revel in the festivities and watch the spectacular migration.

A spark was lit and Jessami got to work. Mukherjee promised to return with more camera traps and train the spotters to use them. Unfortunately, a few months later, in May 2022, violence broke out in Manipur between Meitei and Kuki ethnic groups. Soon, the clashes spread across the state. Mukherjee, who had landed in Imphal with all the required equipment, was forced to go back. “There was no safe route to reach Jessami. We also did not want to inaugurate the community reserve amidst tensions,” said Mukherjee. As violence simmered, the project was put on hold.

For almost a year, Mukherjee, Weyepe, and Nizote desperately waited for a window to open to resume the project. Finally, it was decided that Mukherjee could take a longer route through neighbouring Nagaland to reach the village. Amidst still simmering tensions, Mukherjee and his team are back in December 2023. I join them on this leg. The day we reach, Heshi, Wyeyepe and other spotters lead us to the community forest to show us a large green gate proudly declaring the area as “Jessami Hume’s Pheasant Community Reserve”. The spotters are handed a camera trap that they inspect and learn to use. “You must place the camera trap near a crossroad or opposite a clear area without too many shrubs for clear footage,” Mukherjee instructs as everyone takes turns and practices.

Over steaming cups of chai that evening, the spotters entertain us with stories of adventures from their youth, especially of wild hunts. Nizote and Mukherjee are actively thinking about how conservation and the social development of Jessami can go hand in hand. An isolated border village on the edge of an already politically volatile state, Jessami often struggles to receive state benefits. “There has been no doctor in Jessami for more than one year. The community health centre has only three nurses. The closest doctor is in Ukhrul, about 118 km away,” he says. If the sustainable tourism model takes off in Jessami, he hopes it helps local livelihoods and brings development to the village. “Jessami needs the attention of the state. The bird could save this village,” he says.

Weeks after we leave, Mukherjee tells me that the results of the camera trap footage surprised him and the spotters. Over excited phone calls, the spotters reported the sightings of large Indian civets, Indian wild dogs, and wild boar — species they hadn’t seen in years.

From Hunters to Protectors

Mukherjee is invited to Jessami again to celebrate Tekru-nge on January 22, 2024. For the previous five years, killing animals during the 10-day festival has been banned. Instead, men and women compete in sports to demonstrate skills and physical prowess. This time, the festival is extra special as it will also mark the inauguration of the community reserve. “This is not just about saving the bird”, says Weyepe with hope. “This could protect our cultural traditions in the contemporary context. We can celebrate our festivals and our biodiversity.”

The Guide

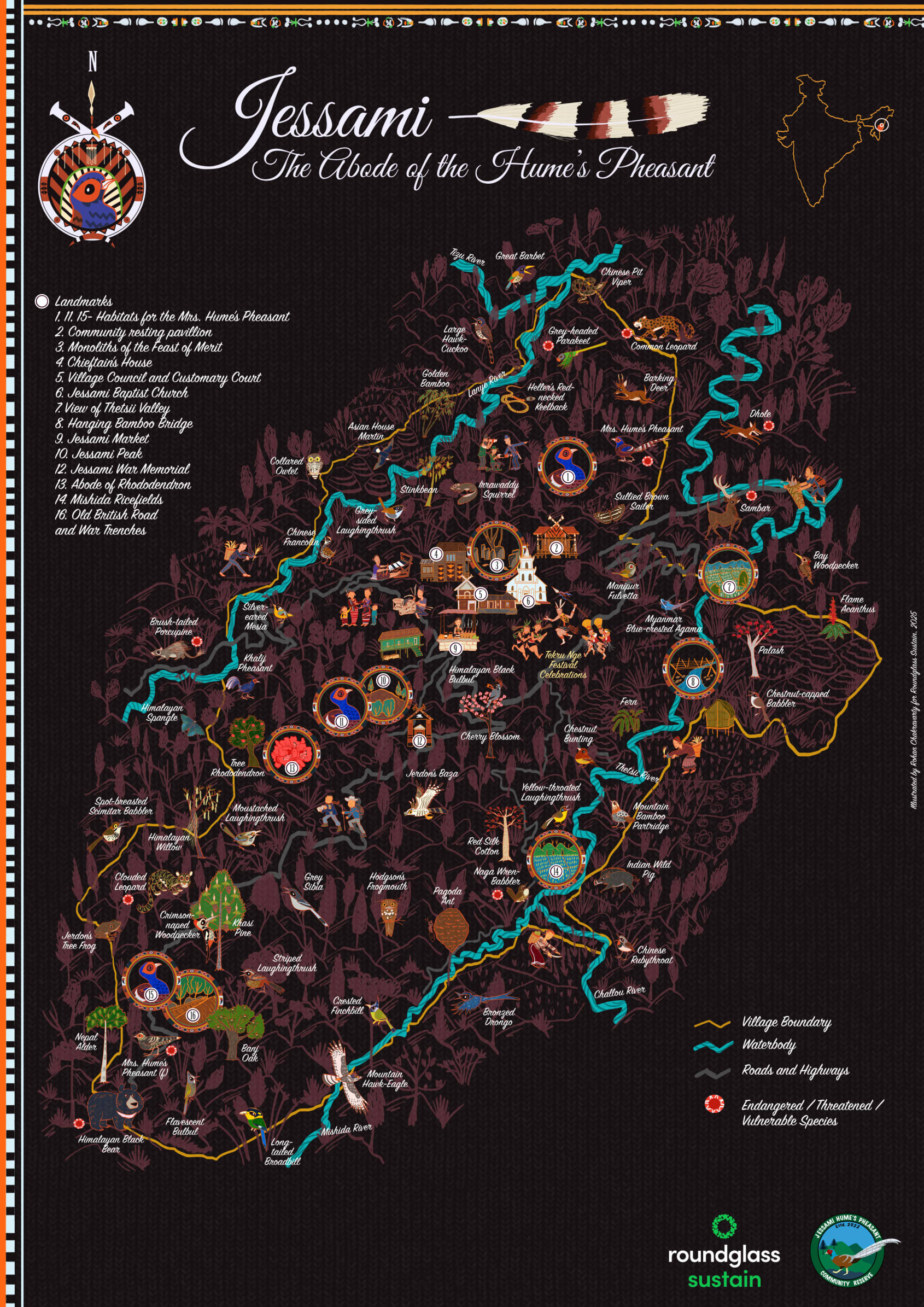

Explore: Jessami Hume’s Pheasant Community Reserve serves as a haven for numerous endangered mammal and avian species: Mrs Hume’s pheasant, clouded leopard, Asiatic black bear, yellow-throated laughing thrush, spot-breasted laughing thrush, among others.

Stay: The local council office offers a basic stay with meals within their complex.

Getting there: Imphal in Manipur and Dimapur in Nagaland have the closest airports, about 7-8 hours away.

Tourism contact: Weyepe N Mekrisuh +91 9717781304