Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Octopuses are cephalopods that are famous for their intelligence and for being masters of disguise. Squids do not receive as much praise but are still widely known. Their close cousins, cuttlefish, however, rarely catch the limelight. But they are truly otherworldly animals.

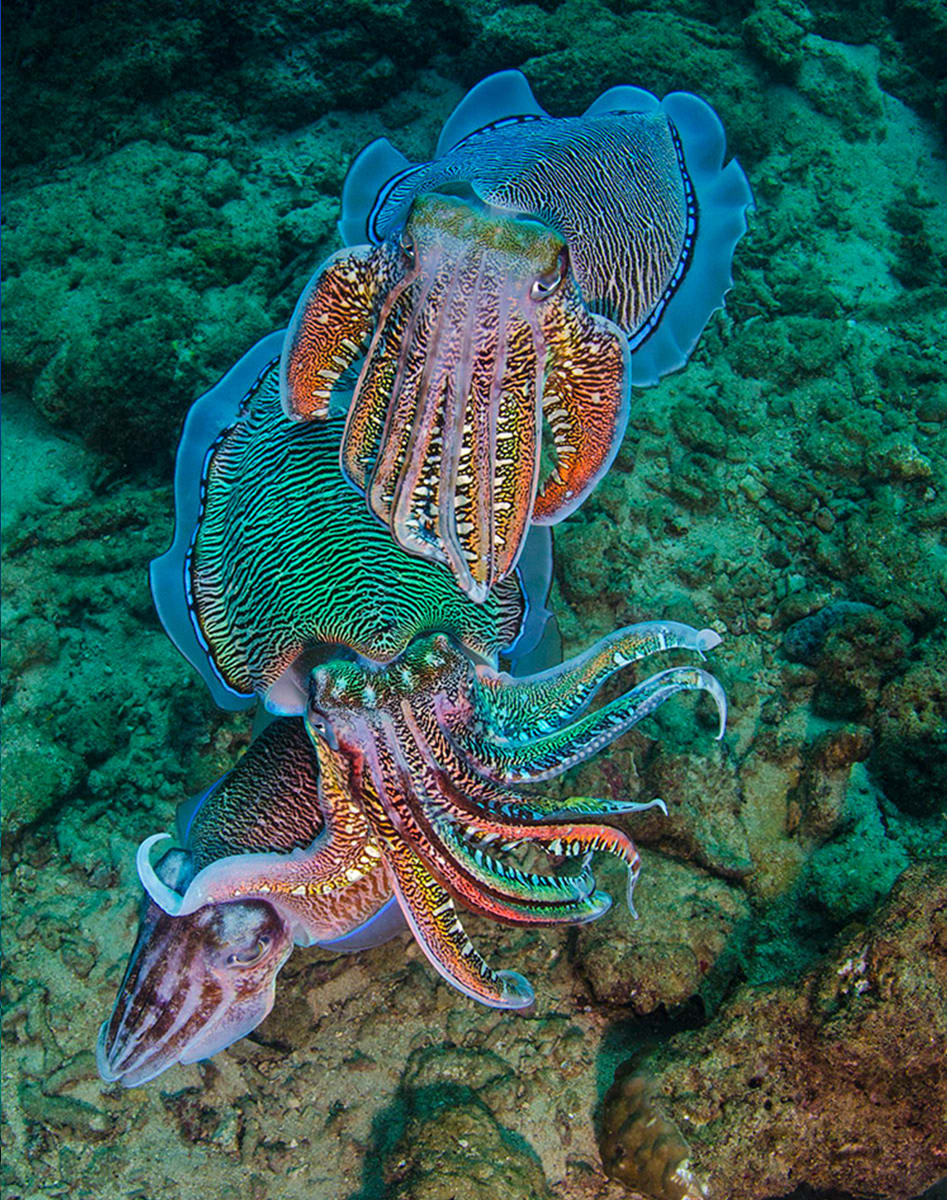

Cuttlefish, like squids and octopuses, are cephalopods (cephalos = head, pods = feet). They have thick, muscular, tube-like bodies with a large head and large eyes. The head has eight projecting arms and two additional tentacles (that are longer than the rest), which they use to grab their prey during a hunt. A thin fin runs the length of their bodies, which undulates rhythmically to propel the cuttlefish forward, sideways, or backwards (or even upwards or downwards). A singular, porous, air-filled bone, called cuttlebone, is present within their body cavity and allows them to control their buoyancy. Centred between their arms, they have a sharp-edged, parrot-like beak, and as though they were not strange enough already, all cuttlefish have a venomous bite.

Though they may be spineless, cuttlefish are some of the most intelligent species on the planet, with intelligence rivalling that of the great apes. Because of their high intelligence and ability to experience pain, they are considered sentient, i.e., animals with the capacity to feel pain or distress and cephalopods have recently been included under the UK government’s animal welfare bill. They are masters of camouflage and deceit; they can change colour, shape, and texture to blend into their surroundings or to trick potential predators.

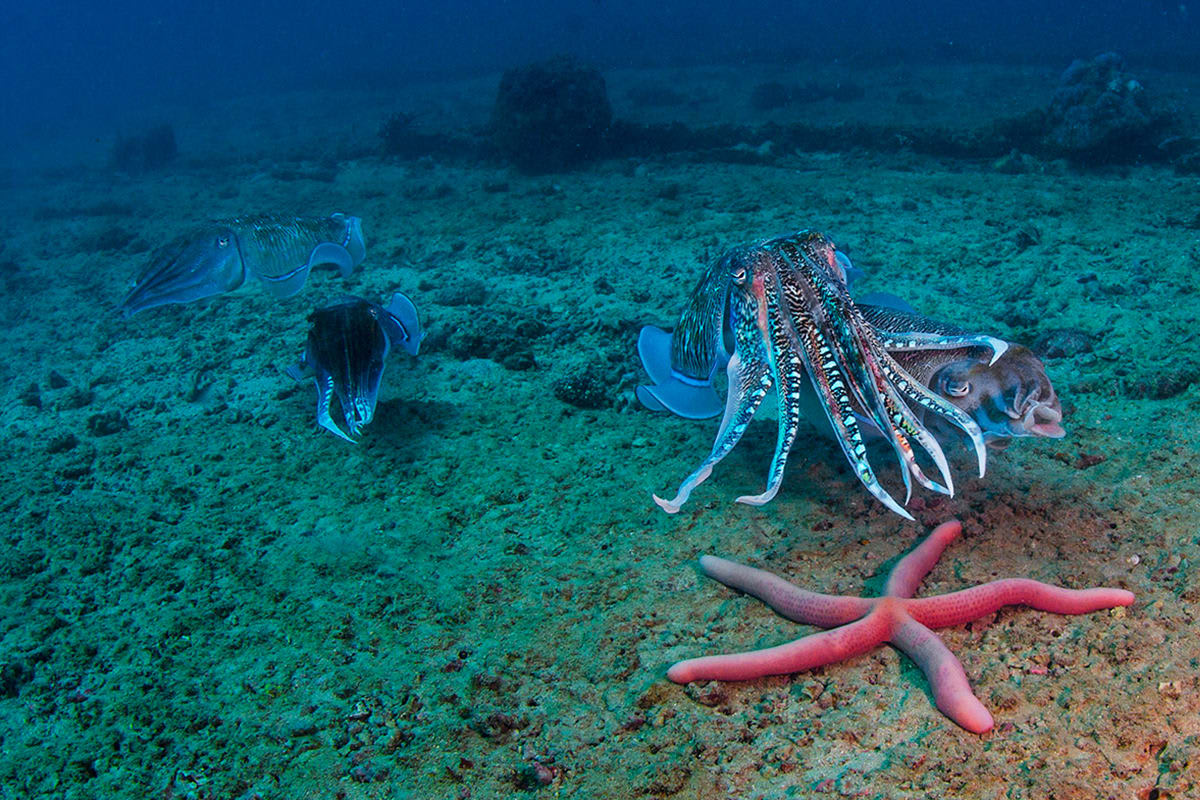

Their intelligence, camouflage, and bizarre physiology are on full display when cuttlefish come to mate. They have striking visual displays involving mate guarding and trickery from rivals. Do the biggest always win? Does an individual’s body side preferences affect their mating success? Let us explore this and more as we journey through the breeding cycle of the pharaoh cuttlefish (Sepia pharaonic).

Alternative mating strategies: Size matters with cuttlefish. Larger males win most stand-offs, scaring off or defeating almost all their smaller opponents. Where brute force does not work, however, small males have developed their own “sneak tactics.” When approaching a female that a much larger male is guarding, small males often wait until the large male is distracted while fending off another opponent and swiftly grabbing their chance to mate with the female. On other occasions, small males might hide in crevices where females may come to lay their eggs. When a female enters the crevice, the male rushes to mate with her, quickly escaping afterwards.

But if both these attempts are unviable, there is one last trick up their sleeve. They change their colouration and posture to mimic a female! Once around a potential mate and her guardian, they flash the non-receptive white stripe on their side to let the male know they are not interested. Since they are as small as the females, the defending male lets down his guard, allowing the sneaky male to nuzzle up to the female and mate with her. By hook or by crook, such males will try to mate.

Egg laying and senescence: After mating, the pair will search for a suitable spot to lay their eggs (preferably crevices within large coral boulders). Each egg is pear shaped and terminates in a long, thin stalk. The female lays multiple clusters of eggs and adheres them to coral or rock by the end of their stalks to prevent them from scattering. Larger females lay more eggs, and the pharaoh cuttlefish seen here can lay between 50-3,000 eggs. These eggs will hatch within three days, releasing baby cuttlefish into the ruthless reef.

Breeding is the cuttlefish’s final act. After spawning, cuttlefish enter a phase of life called senescence, wherein their metabolism slows down, their tissues start to degenerate, and their injuries fail to heal. Slowly but surely, their bodies begin to waste away. Within a couple of weeks after spawning, the male and female cuttlefish will die.