Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

It was a foggy winter morning, like every other foggy morning on Ashoka University’s campus in Sonipat, Haryana. The last vestiges of sleep blurred my eyes, and I hovered between being asleep and awake. Something was poking at my window. “Must be those bothersome pigeons,” I thought. But my clearing vision wasn’t greeted by puttering pigeons. I saw a much larger and whiter bird with a yellow head and curved beak. I was staring at a scavenger vulture, just 10 feet away, tapping at my windowpane. It gave me a sideways glance, realised I was awake, and took off into the fog.

When I first stepped onto Ashoka University’s campus in early 2022, I thought my four years here would be devoid of wildlife. To a wildlife enthusiast, the towering brick buildings and acres of mustard and eucalyptus trees screamed one word — “Meh!”. It was hardly the stuff of wildlife documentaries.

Soon enough, exploring the campus and its surrounding areas, I encountered wild creatures I’d never expected to see. And I’m not referring to the occasional squirrel, but to a whole array of wildlife — from larger animals like monitor lizards, nilgai, and porcupines to snakes and tiny birds like prinias and tailorbirds, hiding in fields or bushes between fields.

A seasonal pond lies within walking distance of the university. Here, I’ve spotted creatures like snipes, sandpipers, moorhens, and nilgai spoor (evidence of their presence). Who would have thought this corner of Haryana held so much wildlife? It was a startling reminder that even in landscapes that are not “natural”, there are mini-ecosystems and wild animals to be found.

This tale seemingly recurs throughout my life. Whenever I think wildlife is vanishing, whenever I feel hope for wild creatures slipping, the universe throws me a lifeline: a feather here, a snake skin there, a large silhouette in the distance.

At no time was this more apparent than when I glimpsed what appeared to be an orange-headed thrush around the ficus trees on campus. I thought I was hallucinating. Surely, this bird I’d spent hours trudging through rainforests and scrub jungle to see couldn’t be browsing near the cricket nets.

A few days later, a friend texted me saying, “Hey, there’s this cool bird hanging around the dhaba. Thought you might like to see it.” Attached was a grainy photo with the unmistakable orange and blue hues of the thrush. I even thought I saw a mischievous glint in its eyes like it sensed the euphoria surging through my veins.

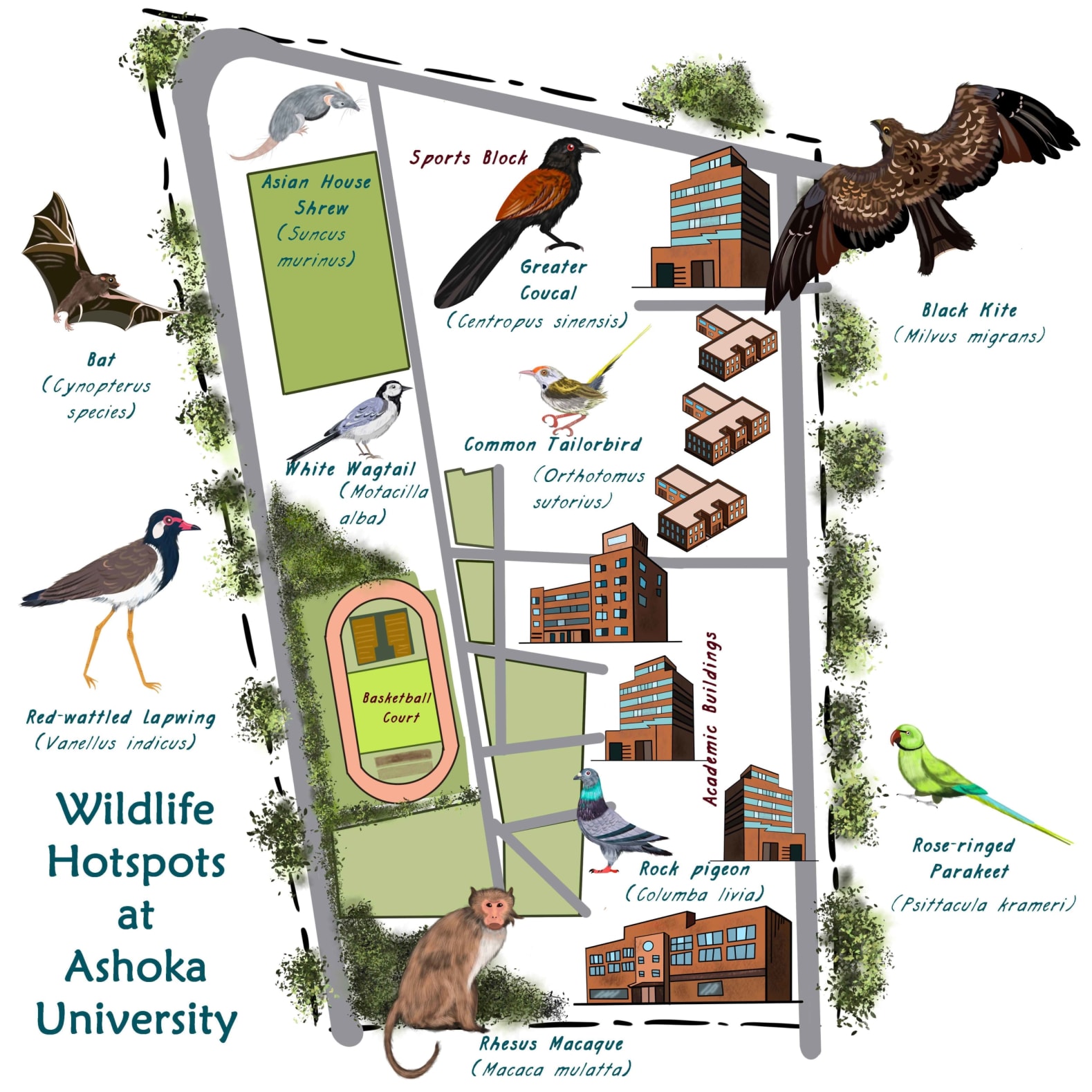

Such instances inspired me to explore the campus and surroundings further. Armed with my phone and curiosity, I began conducting surveys. My mission? To find every single wild creature that lived around me. And the list started to grow, from the red-wattled lapwings on campus that you cannot miss (these noisy birds are everywhere) to less common denizens like grey hornbills and sparrowhawks. In some ways, it’s poetic — these wild creatures calling this house of knowledge home.

To extend my eyes and ears, I started an informal birding group with interested students and experienced professors. I befriended willing didis and bhaiyas, who began taking photos of snakes and other animals they found to add to my growing list. Snakes like the common krait, common wolf snake, and red sand boa would have slipped by undetected if it weren’t for their keen eyes.

During our birdwatching sessions, we spotted migratory birds, even from distant places like Siberia. The Siberian stonechat, for instance, is no bigger than a 50-rupee note and flies 4,000 km to my university. So much for this landscape being devoid of life. Sometimes, I feel like they fly in to remind us that we are more connected than we realise on this planet we call home. It’s an emotion, rumour has it, that still burns in the hearts of all.

As of writing this article, we’ve counted around 130 bird species, and several mammals and reptiles. That number will only grow in the next few years as more Ashokans take up the search. Interestingly, we’ve added to that list by discovering a species of our own! In early 2023, researchers discovered a new species of cricket on the Ashoka campus, appropriately named Hexacentrus ashoka.

Wildlife documentaries and Instagrammers espouse the idea that wildlife is “out there” in a faraway land. To see it, you must undertake grand expeditions to the ends of the Earth. So what does a college student with a burning thirst for wildlife in a featureless landscape do?

While preserving wild landscapes is essential to the conservation movement, we mustn’t conflate it with the idea that these landscapes are the only places bursting with life. Wild heartbeats are everywhere, even in bustling metropolises, agricultural fields, and university campuses.

Don’t get me wrong; wildlife is under siege like never before. As you read this article, wild animals are dying, either from bullets or habitat loss, inbreeding deformities, or other causes traceable to humans. But, by reducing “wildlife” only to those creatures in far-off forests and polar regions, we do a disservice to those animals closer to home.

Often, these creatures are more relatable and thus can be used to educate people about broader environmental trends. Imagine the sparrow as the leading image of the conservation movement. Unlikely, but why not? It is certainly a suitable candidate. You’ve probably noticed their disappearance from places where they were plentiful. Relatable creatures like sparrows can convert disengaged bystanders into stewards of the environmental movement because they prove to us that what scientists say is real — our natural world is suffering. It would befit the honourable Salim Ali that the bird that graces the cover of his autobiography be the icon of a new environmental consciousness.

To test this theory, I compiled a field guide to the fauna in and around my university — a useful resource for everyone to access. I made the online version free because I believe this information should be freely available to anyone who wants it. To my delight, this book has received attention from folks in diverse university departments. Interest in our natural world isn’t the sole prerogative of wildlife enthusiasts. It’s open to everyone.

I’ve learnt that animals in this landscape abide by that timeless creed — the best place to hide is in plain sight. Look closer, and you’ll find a surprising diversity of life. And creatures here are not just surviving; some are breeding, too. In the past years, the Ashoka birding group has identified four individual scavenger vultures in the vicinity and has even observed them mating. I hope many more vultures are on their way. Let their calls ring like a soaring manifesto of hope.

Preparing to graduate, I leave this guide and some maps as resources to inspire all Ashokans to celebrate their wild neighbours. I hope they guide people to understand that the campus and its surroundings belong not only to the humans that dwell here but to all living things, and we should feel honoured to share this space with them. When I return to campus years later as a grey-haired alum, I hope these creatures will still be here, calling this place home. I hope to see nilgai herds roaming outside, stray porcupine quills on paths, and vultures still perching on dorm windowsills.