Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Monsoons in Assam are dramatic. They smell of wet earth and orchids. Rivers swell and spill over, breathing life into nature’s stories, while erasing some forever. As a child, I saw these rains shape the world around me.

I grew up in a small corner of Golaghat district, where people never separated nature from their own stories. How could they, when mornings began with a dozen birds arguing overhead, and children on moonless nights fell asleep on their father’s lap counting fireflies?

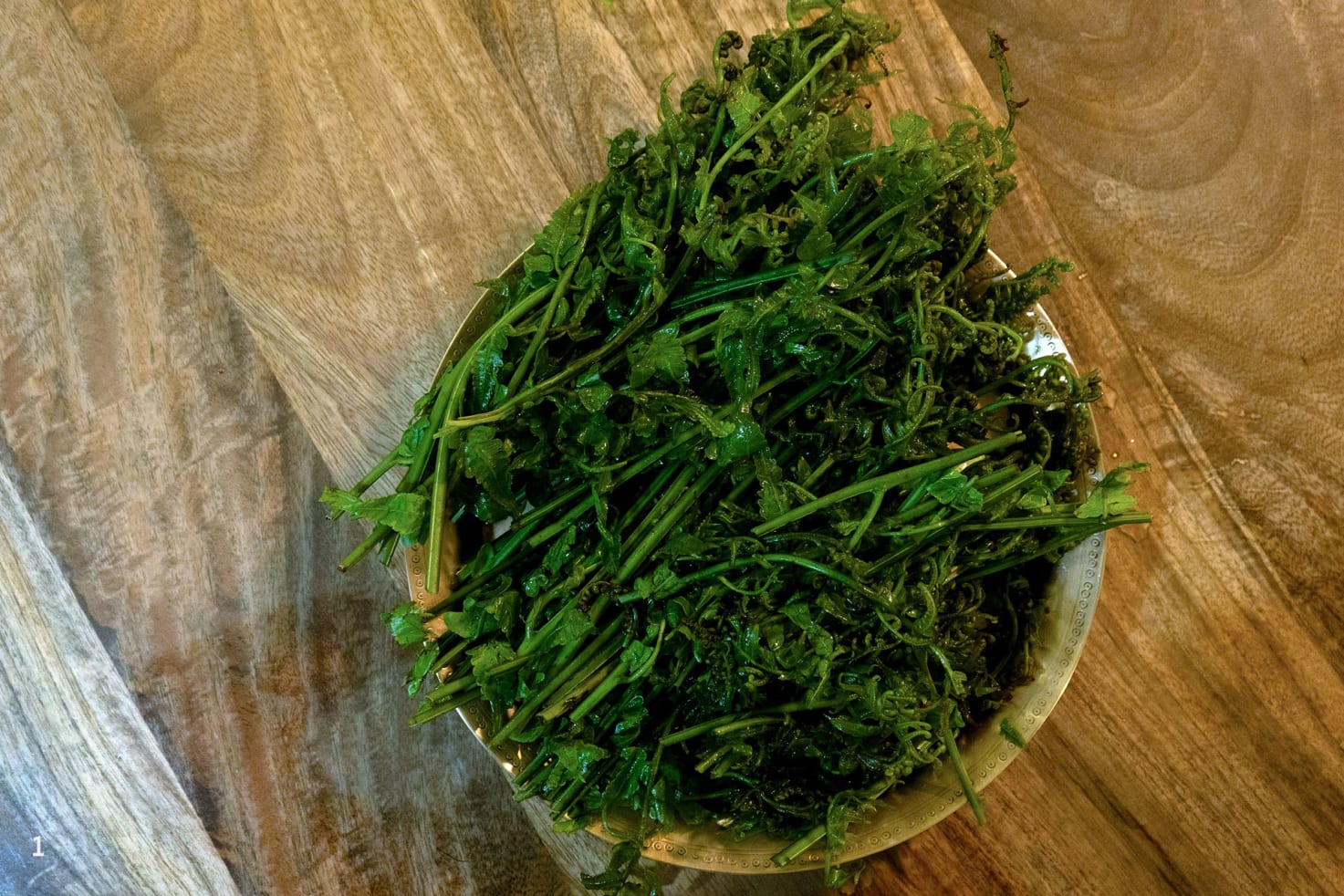

One such monsoon, during the school holidays, my Aapa (maternal aunt) came to visit us with my cousin. We had played ourselves sick that day (quite literally). By afternoon, we were exhausted, a little feverish, and sulking indoors while the rain tapped on the roof. With Maa away, Aapa knew exactly what might cheer us up: dhekia xaak (fiddlehead fern) fried with black chickpeas.

She decided to fetch some dhekia xaak from the wet thickets nearby. My cousin and I insisted on going with her. She warned us about leeches, but we didn’t listen. Finally, she pressed a big umbrella into our hands while she wore a japi; the wide, conical palm-leaf hat, herself. We joined her, still suspicious of leeches, lifting our feet often to check. And amidst plucking the ferns, Aapa told us a story, almost matter-of-factly.

“Do you know, there is a dhekia phool (fiddlehead fern flower)? And whoever finds it, is the luckiest person to exist? He or she would become very wealthy overnight, and their life would be full of prosperity and happiness.” She also added that she knew some people, who knew some people, who claimed to have found the flower and become rich overnight.

She said it was hidden deep inside the forest, and that people believed it only showed itself to those who were meant to see it. Whoever found it would be lucky forever, but one shouldn’t go looking for it out of greed. It can lead them into danger. Not knowing anything about ferns then, I was only interested in the colour of it, and I already had the answer.

Remember Tangled? The Disney movie with a glowing flower that heals? In my mind, the fern’s secret bloom was exactly like that flower, only different, because I wanted to put my own stamp on it. So instead of golden, I imagined it to be purple, glowing with a light only I could see. A ridiculous purple fern flower flickering in the rain. For a while, I forgot about the leeches and kept glancing at the damp undergrowth, half hoping the fantasy flower would blink at me from somewhere.

It was only later, when I grew up and studied biology, that I understood. Ferns are not flowering plants at all. They belong to an ancient group called pteridophytes, plants older than most trees we see today. They don’t produce seeds or flowers but reproduce through spores. The spores grow within soft, little cases called sori, which cluster along the undersides of mature fronds. In the rains and the bright months that follow, the fronds carry little freckles in shades of brown, rust, and gold.

But the fern flower story still remains. A legend born where science disagrees. And this story is actually popular in other places too. In parts of Eastern Europe, in Slavic folklore, a fern flower is said to bloom only on the night of the summer solstice, invisible to most, and bringing love or treasure to whoever finds it. Across places and languages, ferns are entrusted with a secret they never biologically had.

After learning all this, I wanted to test the edges of the legend. Not to puncture, but just to see what else it might be holding. It could be that under the moonlight and dew, sori was shining brightly when someone saw it. Or maybe a glow from fireflies, or a patch of bioluminescent fungi on nearby wood, could have appeared attached to the fern in the dark; enough for stories of sudden fortune to take root. Or maybe these stories were never meant to be taken literally at all. What if they are metaphors? Reminders? That some things in the wild should remain untouched, held apart by mystery. That not everything purple and glowing is ours to pluck or possess.

A legend about a flower you can never see can teach restraint better than a signboard ever will. Yet, it also nudges curiosity: A child who peers under a frond to look for a flower also finds sori, veins, and tiny insects. Small encounters that add up to a way of seeing. Legends both protect and provoke. Perhaps the irony of the fern flower is one such gentle reminder: the forest must always have its secrets, and the wonder itself is worth conserving. But it is just as important for people to know the actual science behind it. Eventually.

Our dhekia xaak is delicious and part of our kitchens. The same plant is also part of a living system that needs its fronds to unfurl, to spore, and to keep the patch healthy. It is the old village sense that some things must be left to ripen, and some spaces deserve our quieter footfalls.

Now, when I walk through different landscapes for fieldwork, I don’t look for the fern flower anymore, because I know it doesn’t exist. But my 11-year-old self probably still believes it does. And in her mind, it will always remain glowing purple, swaying with the monsoon wild, narrated in my Aapa’s voice, curled up like fronds into my childhood fever messily with the scent of fried fiddleheads and chickpeas.