Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

In a fast-changing world, the true wealth of a nation is all too easy to lose if its intrinsic worth is underestimated by its citizens. Food factory, cyclone barrier, fount of myths and legends and human inspiration, the value of the Sundarbans cannot be expressed in mere economic terms. Founder of Sanctuary Nature Foundation, Bittu Sahgal whose association with this mangrove haven spans four decades, asks that the Sundarbans inheritance be protected as a covenant with tomorrow. [1]

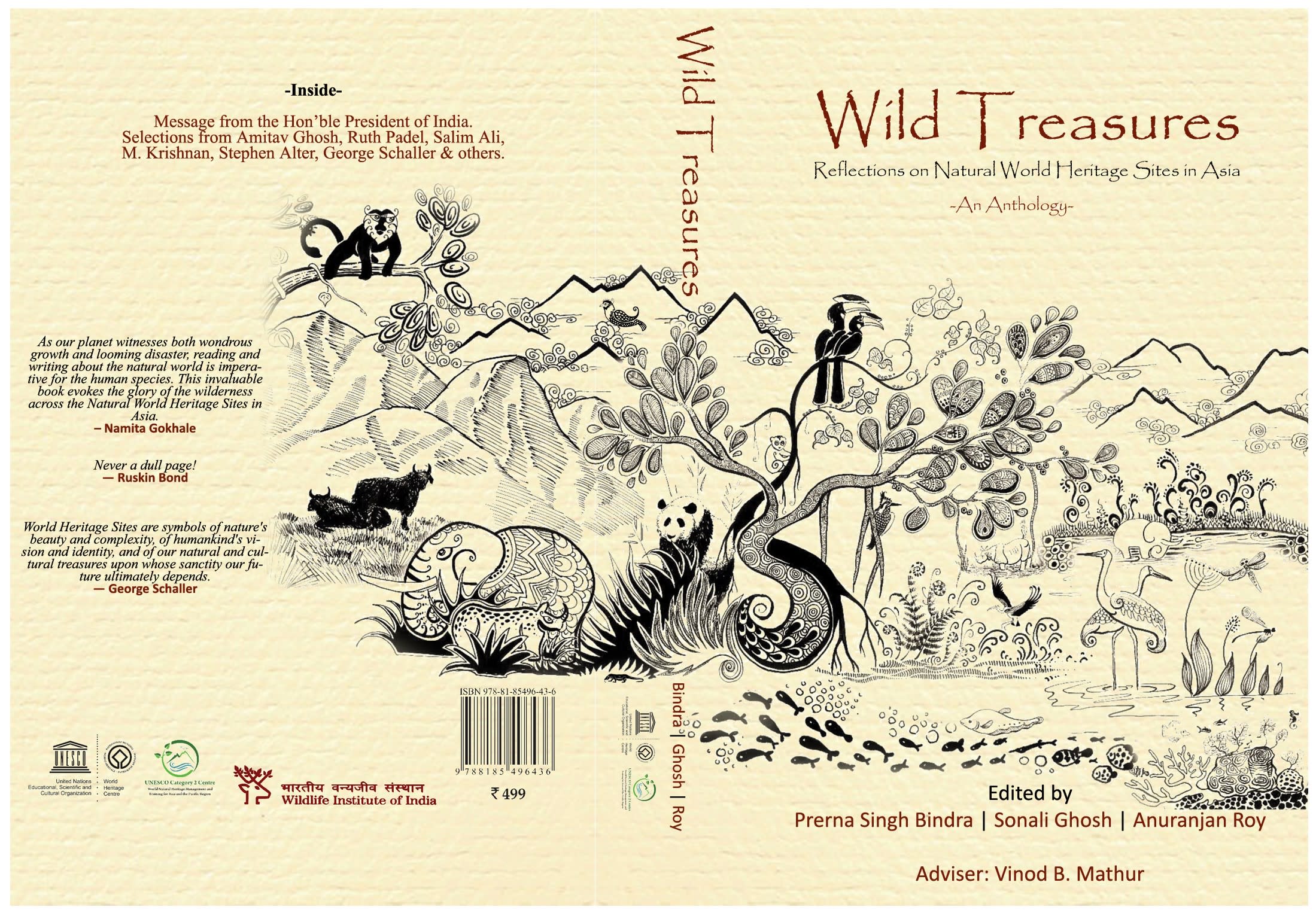

'Wild Treasures: Reflections on Natural World Heritage Sites in Asia - An Anthology' is a collection of 45 articles by journalists, writers, conservationists from some of Asia's incredible natural sites. Photo: Niladri Sarkar / Sanctuary Photo Library

Book cover artwork: Vivek Sarkar

November 1966: I stood on the wooden Kakdwip jetty in knee-deep, mud-brown water, transfixed as snake after yellow-striped, grey-green snake brushed against my legs and swam purposefully past. I thought then that they might have been checkered keelbacks, but more likely they were migrating dog-faced watersnakes, or common smooth watersnakes. I was in a wild land, where the powerful Hoogly river empties into the Bay of Bengal and felt overwhelmed by the sheer vastness of all that lay before me. My love affair with the Sundarbans had begun.

I grew up in Calcutta (now Kolkata), and during those impressionable years, the Sundarbans was always a dark, mysterious, forbidding place “where tigers lived.” As a child, the only tigers I had ever seen were the sorry specimens housed in the Alipur zoo and surprisingly, fear and curiosity tinged with unadulterated awe etched wild images of the Sundarbans in my mind. Back then, even the thought of visiting a forest where tigers lived outside cages would make my pulse race.

I loved the Hoogly river and recall endless boat trips and visits to the famous botanical gardens located on the riverbank. As soon as I was old enough to buy myself a motorcycle, I found myself on a pilgrimage, driving south along the 50 km. road from Kolkata, past Diamond Harbour, past Kulpi, to Kakdwip, just short of Sagar Island in the Sundarbans.

Though Kakdwip fishermen informed me that crocodiles and sharks were common, I never saw either one despite staring long and hard at the open water and mudbanks that lined the estuary. “And what about the bagh (tiger)?” I could never resist asking. And the answer would come: “Mama (uncle)? Not here. Long time ago, he used to live here. Now he can only be found further east, towards east Pakistan (now Bangladesh).”

But I was close enough to dream.

THE INHERITANCE

After several trips and the passage of many years, my fascination for the Sundarbans has grown ever stronger. There is something inexplicably awe-inspiring about the deep swamps… like they exist in a time before the advent of man. And I, like a moth to a flame, have constantly returned.

The moment you enter the tidal world, three colours dominate – blue skies, green mangroves and brown mud. The ‘sameness’ of the mangroves lined mudbanks and the comforting throb of boat engines have a lulling effect as minutes turn to hours, then days in the water world of the Sundarbans. Yet, surprises keep jumping out at you from muddy shores that literally crawl with life.

Those who have not experienced a mangrove swamp of this dimension will find it difficult to comprehend what the Sundarbans has in store for them. It’s a half-way world between land and sea, which offers refuge to both terrestrial and marine species, with the former largely occupying the upper canopy of shrubs and trees, while the latter live underneath amidst the roots and mud. Mangrove plants themselves are ultra-adapted to cope with salinity. To extract pure water from brine, their cells exert a higher osmotic pressure than seawater. Some species have ‘learned’ to shed leaves loaded with salt. Other mangrove species actually possess salt glands and ‘hairs’ that help excrete salt. It is possible to understand the varying levels of salt concentration in the Sundarbans swamps by mapping the distribution of the various mangrove species! In addition, all mangrove fruit and shoots float to facilitate seed dispersal across the oceans. It’s all quite magnificent!

I have been viscerally influenced by the Sundarbans and my desire is to do everything within my capacity to see this mangrove wonderland protected for posterity.

I won’t make any apology for the fact that the magic of the swamps has me in its grip. But, living in an age when technology puts hard information at our fingertips with frightening ease, I am acutely aware that some of the wonderful myths and legends that abound about the Sundarbans are often just that, and not always founded on reality. I am also keenly aware that the ‘invincible’ Sundarbans has almost reached the ‘tipping point’ where further damage by humans could push the ecosystem into an ecological tailspin, from which the tiger and its co-inhabitants may never recover.

The U.N. Food and Agriculture organisation suggests that “mangroves today cover around 15 million hectares (ha.) worldwide, down from 18.8 million ha. in 1980.”[2] Roughly, one million hectares of this globally threatened heritage exists as the Sundarbans, spread across both India and Bangladesh. This is the largest, most biodiverse mangrove ecosystem in the world.

This tangle of plants, channels and islands has sheltered Kolkata and Khulna from the fury of cyclonic winds in the Bay of Bengal for eons, yet few people are even minimally aware of how this mantle of protection governs their lives. Millions who live in the protective shadow of the Sundarbans are even less aware that their fish markets – melting pots of Bengali culture and culinary pride – are direct beneficiaries of the Sundarbans inheritance. Whenever mangroves have been destroyed, anywhere in the world, the fish catch has fallen.

Human inspiration, cultures, religions and philosophies are imbued by the oral history of this little-studied, ethereal swamp that is home to tigers, turtles, sharks, dolphins and migratory waterfowl. A staggering diversity of life forms in the Sundarbans, some awaiting discovery by science, find themselves in a pincer grip between deforestation originating from the north and rising seas (thanks to global climate change) to the south.

This veritable poetry of evolution is under serious threat but nature has the power to repair and renew all… if we allow it to. That is the foundation for all of us to make the joint resolve to work for the protection of the Sundarbans inheritance.

Excerpted with permission from Wild Treasures: Reflections on Natural World Heritage Sites in Asia – An Anthology. Price: Rs 499.

—

[1] This article was first published in Sanctuary Asia’s ‘The Sundarbans Inheritance’ in 2007.

[2] As per more recent estimates, according to the Global Forest Watch and World Resources Institute, in a report from 2015, the world lost 192,000 hectares of mangroves from 2001 to 2012.