Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

My first encounter with Ali Hussain was in October 1980. While involved in the Bird Migration Project with the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), a young, tall individual stood out from the other bird trappers at Keoladeo Bird Sanctuary (not yet a national park then). Bird trapping is a traditional practice among several communities that have lived along wetlands or forests in India. Each community is known to have its own methods, passed on for generations, using snares, nets and other decoys to capture birds either for consumption or selling in the pet trade. In 1990-91, bird trapping was declared illegal (except when it is used for research or treatment purposes), but the practice continues.

In the 1960s, Dr Salim Ali encountered two such communities of traditional bird trappers along the Kabartal wetlands in Begusarai, Bihar — the Mirshikaris and Sahnis. The wetland saw tens of thousands of birds in the 1960s-70s. Today, the wetland is a shadow of its former self. In those days, however, several bird trappers were actively trapping waterbirds during the migratory season ( to sell as food or pets in local markets). Dr Ali worked with them extensively, using their trapping skills for “bird ringing”.

Bird ringing is a research practice of attaching small, light, aluminium rings to a bird’s leg for identification and study. Each ring is coded with a number unique to the bird, much like a vehicle’s number plate, along with details of the organisation that ringed it. When researchers recapture a bird, in India or around the world, they can contact the organisation to obtain data. This allows researchers across the world to monitor bird populations, migration patterns, lifespan, and behaviour. However, to collect substantial usable data, bird ringing must be done on a large scale. Of all the birds that scientists ring, we may, at best, reencounter five per cent of them. Birds migrate long distances, change routes, many die during the journeys, or rings are lost. Encountering a bird you have ringed is low.

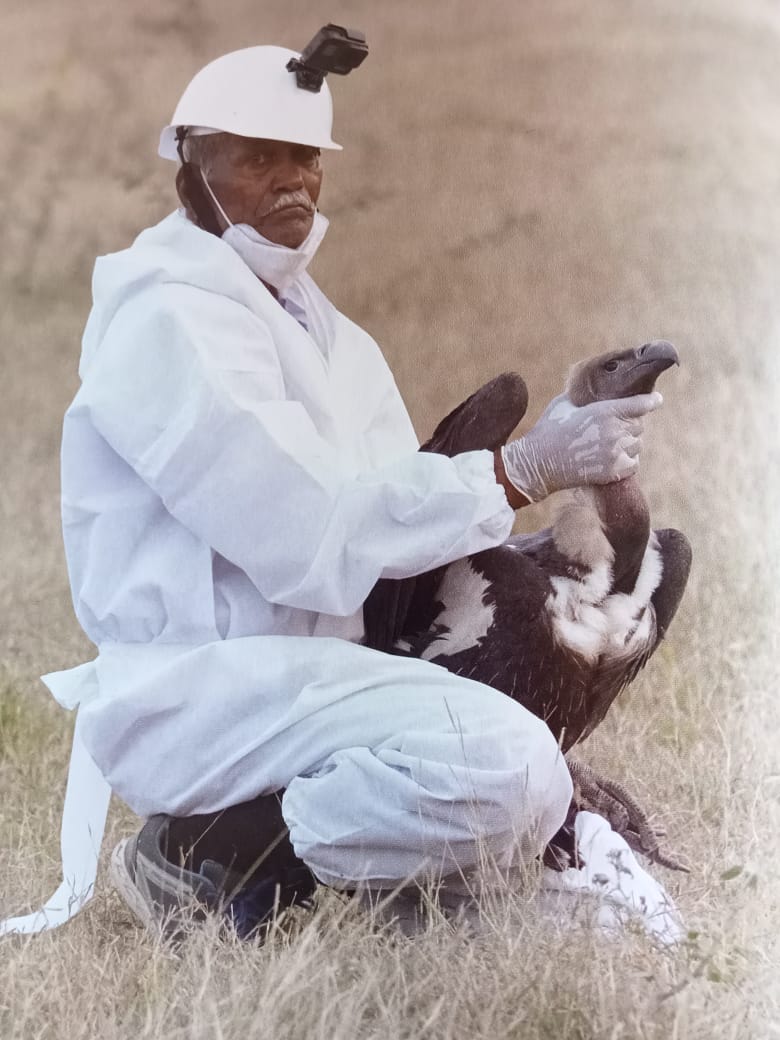

Ali Hussain helps capture and tag a vulture in Gir National Park. Photo: Wildlife Division, Sasan-Gir, Gujarat

Cover photo: Ali Hussain has worked as a trapper for the last six decades, assisting in the conservation of several birds, including a few threatened species. Photo courtesy: Devesh Gadhavi

In October 1980, I was in Keoladeo to ring birds to study their migratory routes. On any given day, we would ring about 250 birds, ensuring they weren’t injured in the process. The role of the bird trapper is both difficult and critical. BNHS had employed 10-12 traditional bird trappers from the Mirshikari and Sahni communities. In a few days, Hussain, from the Mirshikari community, stood out.

Hussain was notably the most vocal, energetic, and assertive, engagingly discussing birds and frequently citing their scientific names. His presence was undeniable, as was his pride in his ancestral bird-catching expertise, achieving near-zero harm to his captures. His extensive knowledge of avian species, behaviours, migrations, and scientific classifications was impressive, and he was not shy about displaying it.

Dr Salim Ali’s team unearthed Ali Hussain’s talent in early 1964 during a BNHS bird-ringing mission in Bihar. He was only 17 years old then. Ali Hussain and his team played a crucial role in catching and ringing hundreds of thousands of birds in northern India. BNHS’s first structured bird ringing scheme ran from 1959 to 1973.

One of Hussain’s unique skills was trapping birds at night, especially on moonless nights, relying simply on the glow of a handheld flame torch. Despite the inherent risks involved (reptiles etc.), he was fearless, and his technique flawless.

In the 1980s, with funding from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), BNHS established major field stations at Keoladeo National Park, Rajasthan, and Point Calimere Sanctuary, Tamil Nadu, and smaller stations at Harike, Karera, Nalsarovar, and Chilika. BNHS recruited Ali Hussain and some Mirshikari and Sahani trappers. The trappers caught birds (primarily waterbirds) at night, and we would ring, measure, and release them early in the morning. For land birds, we utilised mist nets in the sanctuary’s drier areas, assisted by young locals.

Born in 1948, Ali Hussain fathered four sons and two daughters with his wife, Searun Kahtoon. His children are Mehboob Alam, Qasim, Lajeena Khatoon, Sikander and Amjad (both with BNHS), and Rukhsana Khatoon. Qasim assisted his father with the Vulture Programme in the 1990s, which studied the sudden decline of vultures. All four sons learnt bird catching from their father.

Following the end of the Bird Migration Project in Keoladeo NP in 1984, the trappers returned to their home in Begusarai. Some pursued fishing, while Ali Hussain’s family crafted fans from abundant local palm fronds. Nonetheless, BNHS occasionally called in their expertise. When authorised to colour band four bustards in Karera in the mid-1980s, I enlisted Ali Hussain. He and his son, Mehboob, a novice then, exhibited exceptional care in handling the Schedule I species, the great Indian bustard. Ali Hussain meticulously studied bustard behaviour for many days before setting the nooses. We used wheat to attract bustards, placing nylon nooses in foraging areas, a method Ali Hussain had perfected. In about a month, we successfully captured two males and two females.

Ali Hussain and conservation scientist Devesh Gadhavi tag a lesser florican in Naliya, Gujarat. Photo courtesy: Wildlife Division-Sasan-Gir

Our conversations during the long summer afternoons in the small hut included various topics, particularly birds. On one occasion, Ali Hussain corrected my misconception about the number of hoopoe subspecies, showcasing his in-depth avian knowledge.

Ali Hussain’s expertise is not an exaggeration. Those who have collaborated with him can attest to his profound avian knowledge, a culmination of years of bird trapping and subsequent immersion in ornithological literature. When not engaged in enlightening discussions with an attentive audience about his exploits, he dedicates his time to reading or meticulously maintaining his bird nets. Notably, he occasionally poses challenging questions to novice researchers or critiques their limited avian understanding, which can cause some dismay.

Ali Hussain’s lineage (his father and grandfather were bird trappers) bequeathed him a rich heritage of traditional knowledge. He significantly expanded this foundation through his own experiences and observations. His transition from commercial trapping to a more scholarly pursuit of bird knowledge was catalysed by his association with Dr Salim Ali and BNHS. Today, I regard him as the preeminent bird trapper and naturalist of the Indian subcontinent.

Hussain’s exceptional trapping skills encompass nearly a hundred techniques, many tailored to distinct species and habitats. He garnered the attention of the US Fish & Wildlife Service, which sponsored a month-long visit to the US so he could impart his expertise to American bird experts. Accompanied by his son Mehboob, and under the guidance of Mini Nagendra from USFWS, Ali Hussain captivated American wildlife officials with his diverse trapping methods, especially his claptrap and noose-trap techniques. His renowned claptrap method, documented in the “Proceeding of the North American Crane Workshop” (2008), was pivotal in capturing nonmigratory whooping cranes in Florida. He was celebrated for his efficiency and safety in capturing multiple cranes simultaneously. I learned that he successfully trapped 10 per cent of the Mississippi sandhill crane population, leaving the American scientific community in awe.

Presently, Ali Hussain and his sons and relatives remain sought-after figures for avian capture in research projects. BNHS holds him in high esteem, enabling him to interact with top officials comfortably. His reputation often precedes him, instilling a sense of accountability in those who employ his services.

In 1998, the Films Division of the Government of India produced a short documentary on Ali Hussain. It has been translated into 18 languages and screened across India, occasionally in theatres before the main feature film (now available on YouTube). Ali Hussain has received many awards for his expertise in catching birds for migratory studies. He is a masterful bird-trapper. I think even the birds feel blessed when they pass through his hands!