Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

“The question is not what you look at, but what you see.”

– Henry David Thoreau

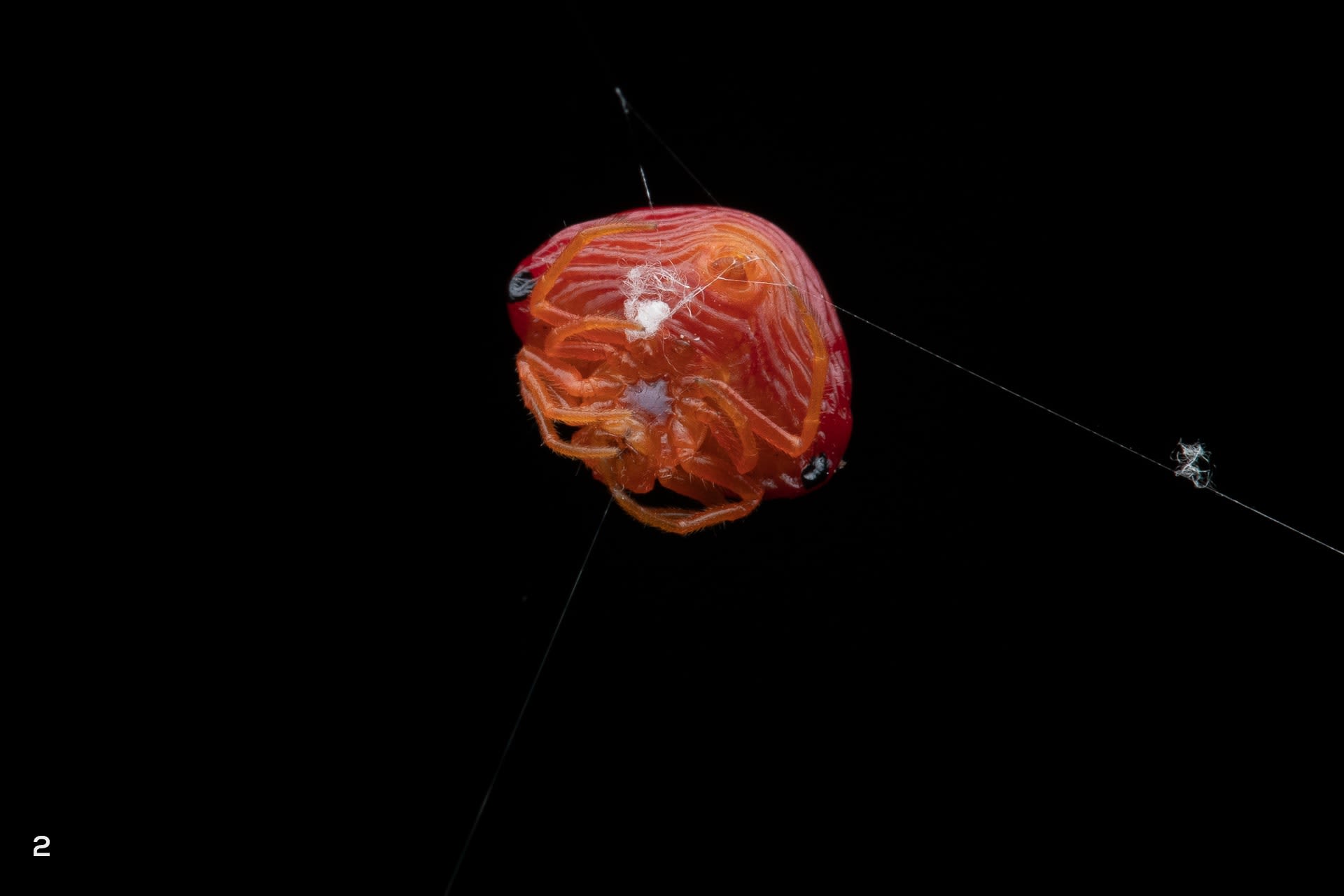

Do you enjoy a good visual puzzle? Do you love an optical illusion that baffles and blows your mind when you finally decipher it? Then, a stroll, looking for cryptic spiders, is just the thing for you. Spiders are among the most complex living puzzles ever designed. There are spiders that resemble parts of a plant; spiders that look like snails (lead image); others that look like ladybird beetles; and even spiders that look like bird poop. The most popular mimics from the spider world are from the ant-mimicking genus Myrmyrachne — each species in the genus mimics a model ant species. For instance, Myrmyrachne plataleoides exclusively mimic the weaver ant species Oecophylla smaragdina.

Why go through the trouble to look like something else? In most cases, the disguised spider is trying to evade potential predators. In a study titled “A Predator’s Perspective of the Accuracy of Ant Mimicry in Spiders”, published in Psyche: A Journal of Entomology in 2012, the authors conclude that “…ant resemblance confers protection from visual predators, but to varying degrees depending on signal accuracy”. The study supports the seemingly intuitive idea that a spider has a better chance of evading its predators if it more closely resembles its model. In looking more like an ant, they are likely to evade predators ranging from birds to other spiders who are wary of hunting an ant and dealing with the threat response of colony mates.

Each of the mimics in this story gains specific advantages by looking like their model (morphological mimicry). Brightly coloured ladybird beetles are unpalatable to a lengthy list of predators; bird poop is an acquired taste reserved for detritivores who do not pose a serious threat to spiders; and a twig or dried leaf isn’t on the menu of a spider’s natural predators.

Spiders from the genus Paraplectana are among the most vivid examples of morphological mimicry. They stick out to blend in with the right crowd. Ladybird beetle-mimics like this Paraplectana rajashree have shiny rounded abdomens with black spots to mimic ladybird beetles from the genus Coccinella. Even when these orb-weaving spiders (2) move along a line of silk or (3) sit on their orb-webs, they maintain a cryptic ladybird-beetle-like pose with their legs tucked in.

Coccinella beetles, like many other brightly coloured things in the natural world, are toxic to predators such as birds, spiders and many other insect-eating creatures. Through the course of an evolutionary learning curve, predators such as insectivorous birds have learnt to avoid brightly coloured beetles because these beetles are packed with alkaloids — chemicals that will likely leave the bird with a foul taste in its mouth and discomfort in its tummy. In fact, the bright colours and patterns on their bodies serve as a warning signal to predators (aposematism). The vibrant warning signals ensure predators leave them alone without taking a bite first. In this “eat me at your own risk” world of aposematism, mimics like Paraplectana simply adopt the warning signals without necessarily being toxic. This nifty phenomenon of a species looking like a poisonous or foul-tasting species while being perfectly palatable to a predator is called Batesian mimicry.

Over the millions of years that spiders have been around, they’ve done incredibly well to look like other things. As predators evolve new ways to see through the illusions of mimicry, the mimics evolve new ways to perfect their craft. For instance, wasps that predate spiders use chemical cues to zero in on their prey. To counter this, some spiders may evolve chemical means of evading wasps.

How, then, do you look for these nearly perfectly disguised spiders without the olfactory abilities of a wasp? What humans lack in sensory superpowers is often compensated for by our ability to take information and use it to look at the world from different perspectives. Diving into this fascinating world of mimic spiders and deciphering their camouflage requires two things — keen observation and malleable perception. You will have to look closely at everything that raises suspicion even to find the puzzle (most of the spiders you’re looking for are smaller than a fingernail). Once you’ve focused on something that could be more than it seems, explore every perspective with reason. Why does this ladybird beetle have eight legs? Why is that piece of bird poop moving gracefully along a line of silk? You may be looking at a twig, but do you see that it is actually a spider?