Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Male pheasants are renowned for their dazzling plumage and dramatic courtship displays, and the grey peacock-pheasant (Polyplectron bicalcaratum) is no exception. While it may lack the extravagant “tail” of the Indian peacock (Pavo cristatus) or the great argus (Argusianus argus), its display is no less remarkable. (Note: What is popularly referred to as a peacock’s “tail” is actually a train of elongated upper tail-coverts, not true tail feathers.)

In contrast, the grey peacock-pheasant’s showpiece is made up of genuine tail feathers. These feathers are broad, rounded, and decorated with prominent eyespots (ocelli) that shimmer with metallic or iridescent hues. During courtship, the bird fans its tail laterally, holding it upright or angled like a traditional hand fan. While its display may appear more modest than the Indian peacock’s flamboyant performance, it is more refined and intricate. Notably, unlike the peacock, this species uses actual tail feathers, making its display both anatomically and behaviourally distinct, even though both birds share the use of eyespots and tail fanning to impress mates.

One of the most vivid descriptions of its courtship ritual appears in The Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan (Volume 2, Page 121) by Dr. Salim Ali and Dr. S. Dillon Ripley:

“The cock’s display is both beautiful and spectacular. He starts by running around the hen with his tail partially fanned and wings spread low. He then crouches in front of her until his chest touches the ground, raising and spreading his tail and wings into a fan to flaunt the iridescent ocelli. His head, half-hidden in the ruffled plumage, completes the pose. The hen usually appears indifferent but may occasionally respond with a subdued version of the same display, followed by copulation.”

Although I have never observed this display in the wild, I recall witnessing it once in the Lucknow Zoo, where up to eight grey peacock-pheasants were housed together. The performance was mesmerising — until noisy visitors interrupted it. I know that two birds are present in Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park in Darjeeling, but I am unsure of how many of these birds are currently housed in other Indian zoos.

There are eight species of peacock-pheasants found across South and Southeast Asia, but only the grey peacock-pheasant is native to India. Two subspecies are recognised in the Indian subcontinent: Bhutan peacock-pheasant (Polyplectron bicalcaratum bakeri) and Burmese peacock-pheasant (Polyplectron bicalcaratum bicalcaratum). The former is named after EC Stuart Baker, a British police officer and ornithologist of the Northeast during the colonial period. The latter subspecies is found in the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh, near the Indian border.

The grey peacock-pheasant is a terrestrial forest bird, measuring about 48 cm in females and up to 64 cm in males. Both sexes are cloaked in grey-brown plumage with striking iridescent markings on the wings. Males sport a longer tail and a distinctive bushy crest that arches forward. They inhabit dense forests with thick undergrowth, moving stealthily like phantoms and rarely venturing into the open. Their vocalisation is a series of harsh, rising croaks, typically heard in the early mornings.

Interestingly, when Drs Salim Ali and Ripley described the species in 1969 as “smallish pheasants reminiscent of spurfowl,” they were unknowingly foreshadowing modern molecular findings, which reveal that peacock-pheasants are indeed more closely related to spurfowls (genus Galloperdix) than peafowls (genus Pavo).

Thanks to their adaptability and ease of breeding, peacock-pheasants have long been popular aviary birds, housed in many zoos around the world. In India, the Central Zoo Authority once maintained a studbook (genetic and demographic records) to track and manage the captive population. According to Dr Rajat Bhargava, former aviculturist and senior ornithologist with the Bombay Natural History Society, this species was a favourite in avicultural (captive breeding and keeping) circles until the early 1990s, when the Government of India implemented a blanket ban on native bird trade in 1990-91. Previously, wild birds — especially those from the Goalpara region — were acquired by bird dealers from Kolkata and Patna and supplied to zoos and private breeders nationwide. By the early 2000s, most captive birds had died out. Dr Bhargava notes another key reason: once it became illegal to keep native birds, many private aviculturists lost interest in maintaining or breeding them, and even zoos began to receive fewer specimens.

However elusive and challenging to photograph in the wild the grey peacock-pheasant may be, it is not classified as threatened by the IUCN. It inhabits several protected areas across Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Manipur, and Nagaland. Despite its secretive behaviour, there are nearly 500 photographs of this bird on eBird, many taken in zoos or private aviaries, and over 4,500 sightings, although many are entries repeated from the same sites.

One of the most respected bird guides in Northeast India, Abidur Rahman, based in Bokakhat, Assam, brings valuable field insight. Leading birding tours across Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, he writes: “The Grey Peacock-Pheasant is fairly common in the foothills of the Eastern Himalayas and throughout Northeast India. Although hard to spot due to its shy nature, it is widely distributed across its range. Its call is distinctive and audible in suitable habitats, especially bamboo and cane thickets. It can be heard regularly in places like Namdapha, Mehao Wildlife Sanctuary, and Eaglenest in Arunachal Pradesh, as well as in Dehing Patkai and Kaziranga National Park in Assam.”

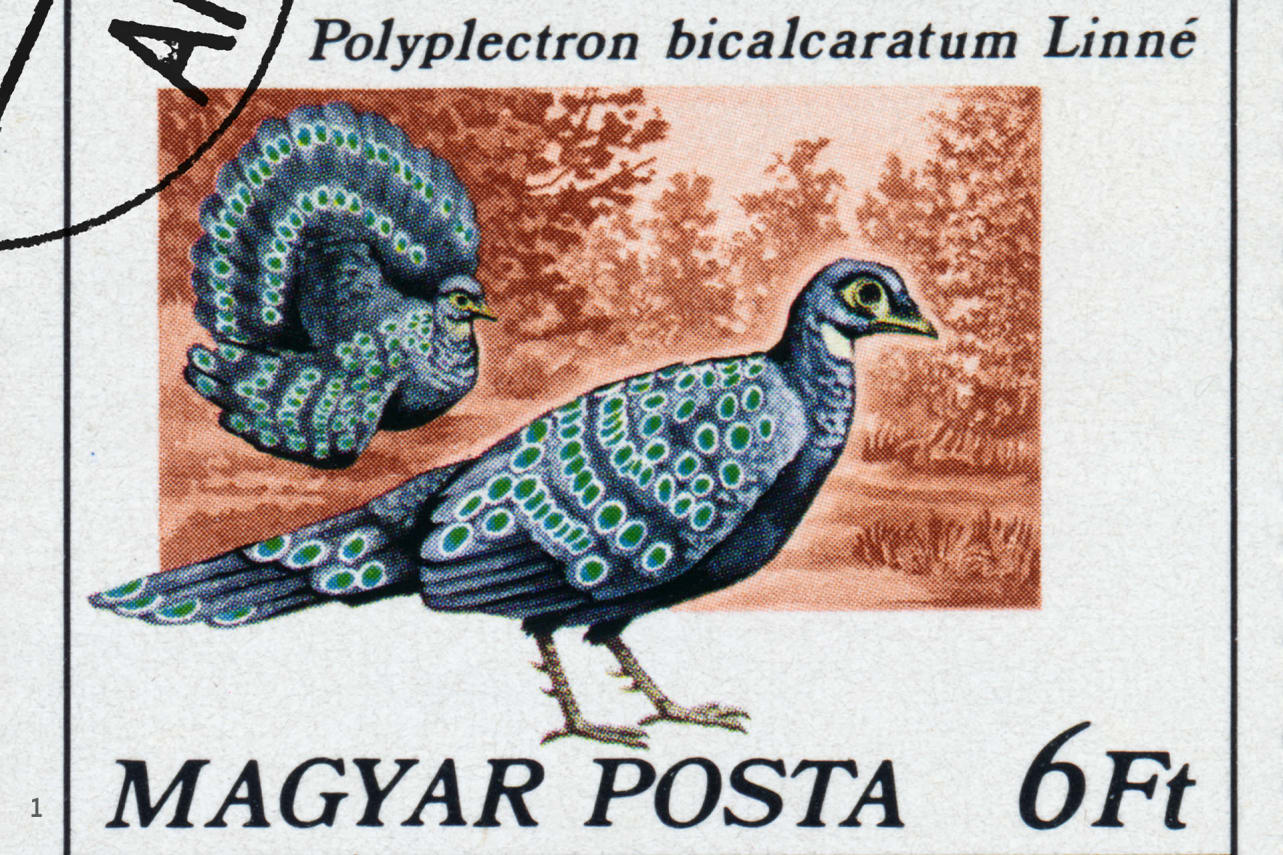

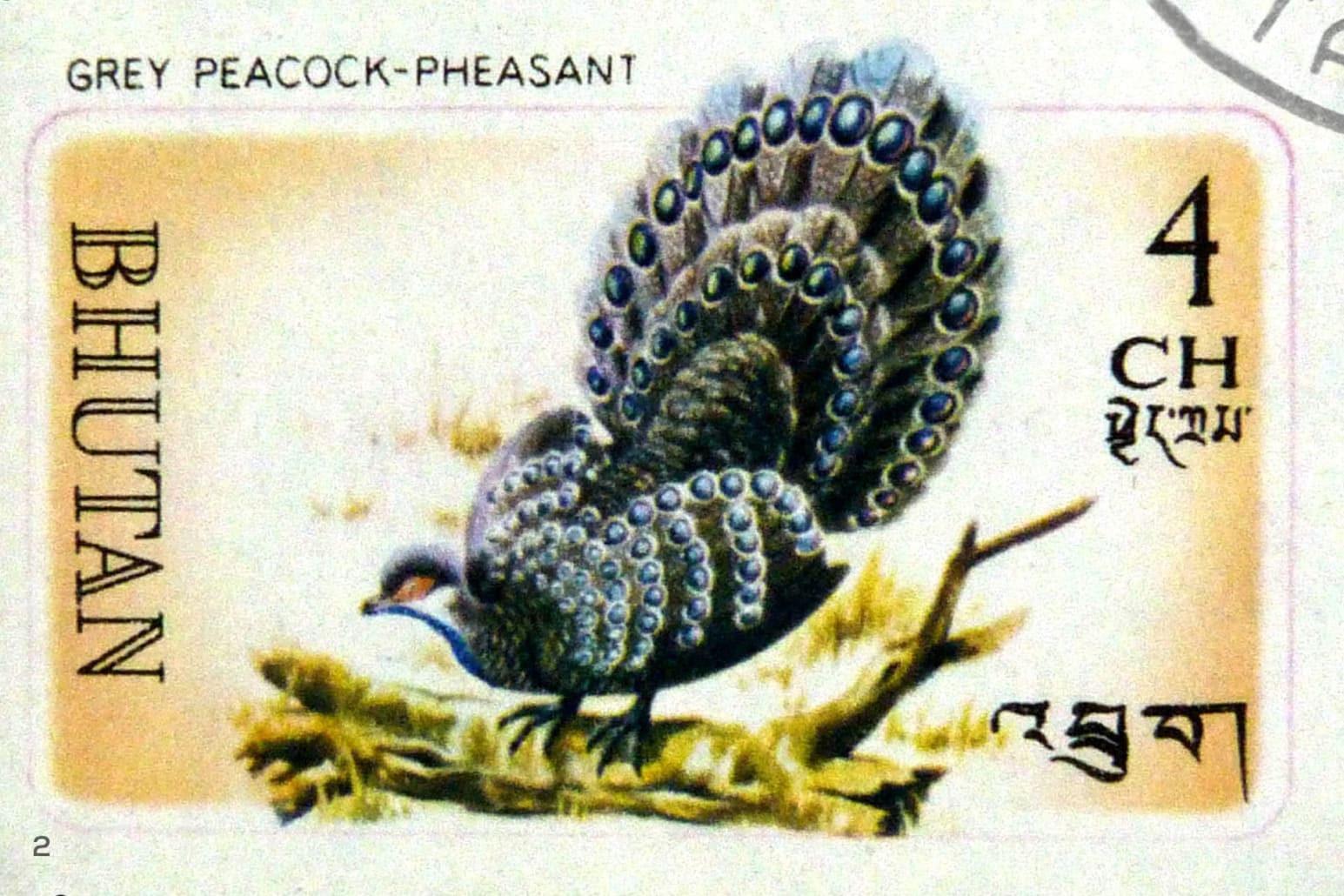

Ironically, while countries like Singapore, Malaysia, Bhutan, and Hungary, and The Gambia — where this bird is not found — have issued postal stamps featuring peacock-pheasants, India has yet to do so.

The Central Zoo Authority (CZA), under the Ministry of Environment, Forests, and Climate Change, has listed the grey peacock-pheasant for conservation breeding, designating Alipore Zoological Park in Kolkata and Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park in Darjeeling as breeding centres. Personally, I believe such a step is unwarranted at this stage. The species is currently not at risk of extinction and is thriving in several well-protected habitats. Our primary conservation focus should instead be on preventing poaching and safeguarding natural habitats. Even if we succeed in breeding a large number of these birds in captivity, where will they be released if the forests they need are gone?

Unfortunately, many conservation actions in India tend to be driven more by emotion and glamour than by scientific reasoning and species’ global status. Zoos, while valuable for education and public engagement, are not always the ideal venues for conservation breeding of threatened species. The complex science of conservation breeding requires a very different approach.