Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

What is the most suitable way to describe an oyster? For a seafood connoisseur, it is a soft, slippery, salty shellfish with earthy notes. The textbook classification refers to it as a bivalve mollusc that lives in marine and brackish waters. But there is one more title, which some might find the most mysterious and precious of them all: it is the enigmatic maker of pearls. Oysters are each of these and much more. Oysters are an integral part of the story of the ocean. This article attempts to tease apart slivers of their story, especially the parts we typically do not think about or get to see, for it would require us to journey into the underwater world. Oysters in the wild!

Cover Photo: Umeed Mistry

What is an oyster?

Oysters are soft-bodied invertebrates that produce external shells made of calcium. We group them under the taxonomic group or phylum Mollusca along with other shell-makers like snails, as well as other squishy invertebrates with internal shells (or absent altogether) like slugs, squids, cuttlefishes, and octopuses. An oyster’s body is a soft, vulnerable mass containing all its internal organs, a mantle, foot, and head. A calcified external shell protects it from predators, physical damage, and dehydration.

Within molluscs, oysters belong to a particular group of snails that make two shells, mirror images of one another, connected by a hinge. These organisms are called bivalve snails and include clams, scallops, cockles, and several other snails whose shells open and close at a hinged joint.

Like all bivalves, oysters have a pair of strong adductor muscles attached to their shells, which allow them to open their shells when it is time to filter feed on plankton or remove debris, and keep them sealed when threatened. Oysters are typically attached and cemented to other structures in their habitat, although this is preceded by a period when they live as free-swimming larvae in the plankton.

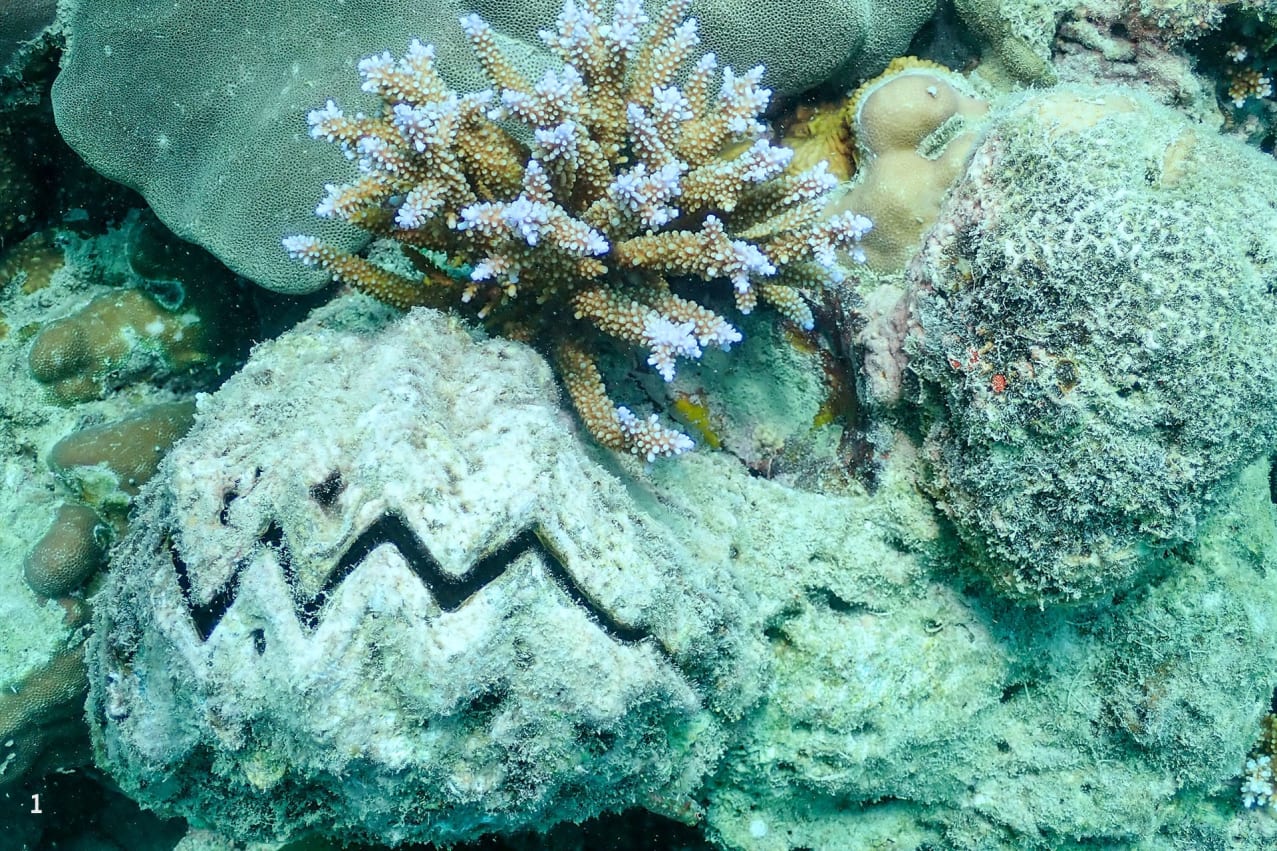

Where would we go to find wild oysters? Depending on the species, oysters live in habitats as shallow as the seashore or in reefs 30-40 metres deep. On reefs, you will see them attached to rocks and overhangs and even piggybacking on other animals like soft coral, giving them access to strong currents carrying plankton. Closer to shore, oysters can be seen studded across rocks in tide pools and dense colonies or “oyster reefs” in brackish waters and mangroves.

Wherever they are found, whether singly and underwater or as colonies on the coast, oysters act as ecosystems in themselves. Given their sessile (permanently attached) lifestyle, they offer stability to a plethora of organisms, from stationary creatures like barnacles and tunicates to mobile crabs and passing schools of fish.

Oyster predators

Many creatures love a good oyster, not just humans. Oyster predators have evolved diverse machinery and strategies to get through the oyster’s calcified exterior and strong musculature.

Crushers: Strong pincered crabs like swimming crabs, mud crabs, and red-eyed crabs can crush and dismantle an oyster’s shell to get to the soft body hidden inside.

Smashers: Oysters that live along the shore have to be wary of marine predators and carnivorous birds like Eurasian oystercatchers and ruddy turnstones. These birds can rip oysters off their substrate and use their bills to pry open the shells. They might also smash them to pieces to get to the soft tissues.

Drillers: Carnivorous snails like the moon snail, murex, triton and crown conch have radulae (tongues) modified into a raspy drill that can make clean holes in the surface of their prey’s shell. Before they do this, they first secrete an acid to soften the calcium shell, making drilling easier. Without going through the effort of destroying any more of the shell, they slurp up the oyster inside.

Pearl maker

For centuries, what has captivated our imagination the most about oysters are the precious pearls they make. A squishy creature holed up inside hinged shells can produce these lustrous beauties that have symbolised elegance, class, and purity in the human world for centuries.

Not all oysters produce pearls. Pearls are the handy work, or rather “mantle work”, of a group of oysters in the family Pteriidae. Pteriid oysters are typically found across shallow habitats in the tropics and subtropics. When an irritant, typically a parasite, enters an oyster shell, the animal releases a complex secretion called “nacre” around the irritant to protect itself. Nacre, also known as “mother of pearl”, is a mixture of 95 per cent calcium carbonate crystals and 5 per cent organic material (proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and chitins). The mantle secretes nacre slowly around the irritant in what scientists describe as a “brick-wall-style” of stacking layers. This makes the pearl resistant to fracture. The lustre, sheen and rainbow effect that pearls and the inner layer of oyster shells produce results from how light interacts with the different minerals in the pearl.

Oysters are fascinating and mysterious creatures tied to so many others in the web of life as food, habitat, and as influencers of ocean chemistry. But oysters share a similar future as several other marine invertebrates — one laced with threats. Habitat loss and degradation due to destructive fishing threaten their health and populations, as do pollution, disease, and overharvesting. Plus, they are impacted by ocean warming, acidification, and rising sea levels.

For those of us who are learning about the lives of oysters for the first time, the best place to begin oyster appreciation is at the nearest shore. Our beaches a filled with evidence of their existence, from washed-up oyster shells glistening in the sun with that inner layer of nacre to intertidal rocks studded with white blotches that you may have mistaken earlier for a whole lot of bird poop!