Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Listen to this article

•

15:34 min

Media outlets in Nepal were recently abuzz with reports that the country’s iconic Bengal tigers (Panthera tigris tigris) were moving to India in search of better habitats. In Nepal, the government and various NGOs spend large sums of money every year on the protection of the tiger.

The story resonated with the public, given that thousands of Nepali people make a similar journey across the open border everyday, into the southern neighbour, in search of better jobs and incomes. “As India is doing a better job at managing its tiger habitats, Nepali tigers are crossing the border to move to greener pastures,” one media report said.

Following the reports, Nepal’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife Reserves said it was preparing plans to encourage “Nepali” wild animals to stay in Nepal.

The episode highlights one of the key human-induced challenges facing efforts to conserve the Bengal tiger population in its joint stronghold of Nepal and India: “animal nationalism,” or the belief that certain wildlife belong to a particular country.

A century ago, it was estimated that there are more than 100,000 wild tigers across Asia. By the early 2000s, their number had plummeted by 95%, largely due to poaching and habitat loss and fragmentation. During this time, three subspecies — the Java, Bali and Caspian tigers — went extinct.

In 2010, the governments of tiger range countries committed to doubling the tiger population by 2022, the year of the tiger in the Chinese zodiac. Since then, the population of Bengal tigers has bounced back, with Nepal and India leading the way toward achieving the goal.

Cover Photo: Tigers don’t recognise political boundaries and have always roamed a wide range along the Indo-Nepal border, yet even this behaviour is under threat as key corridors are restricted or cut off entirely by infrastructure projects by both countries. Cover Photo: Sriram Giridharan/Shutterstock

On July 29, International Tiger Day, Nepal is expected to announce the achievement of the goal of doubling the population, at least in some of its protected areas.

Tigers have historically moved freely between ranges in Nepal and India, establishing a rich genetic pool. “When we compared photographs of 10 tigers in Nepal and India obtained through cameratraps [in] 2013, we found that they were frequenting both India and Nepal,” said Baburam Lamichhane, a conservation biologist at the National Trust for Nature Conservation, a semi-governmental body in Nepal.

However, these movements are becoming increasingly restricted due to a host of challenges, and compounded by a sense of “animal nationalism” that threatens to fragment populations in the two countries.

“Animals don’t care which land belongs to Nepal and which land belongs to India,” says conservationist Narendra Man Babu Pradhan, a former warden of Nepal’s Chitwan National Park who now works with IUCN, Nepal. “But it hasn’t been easy for humans to understand that.”

Governments and NGOs on both sides of the border spend a lot of money and resources trying to shore up the population of tigers. As their performance is judged by the number of tigers counted in the census, the cross-border movement of tigers becomes an accounting problem.

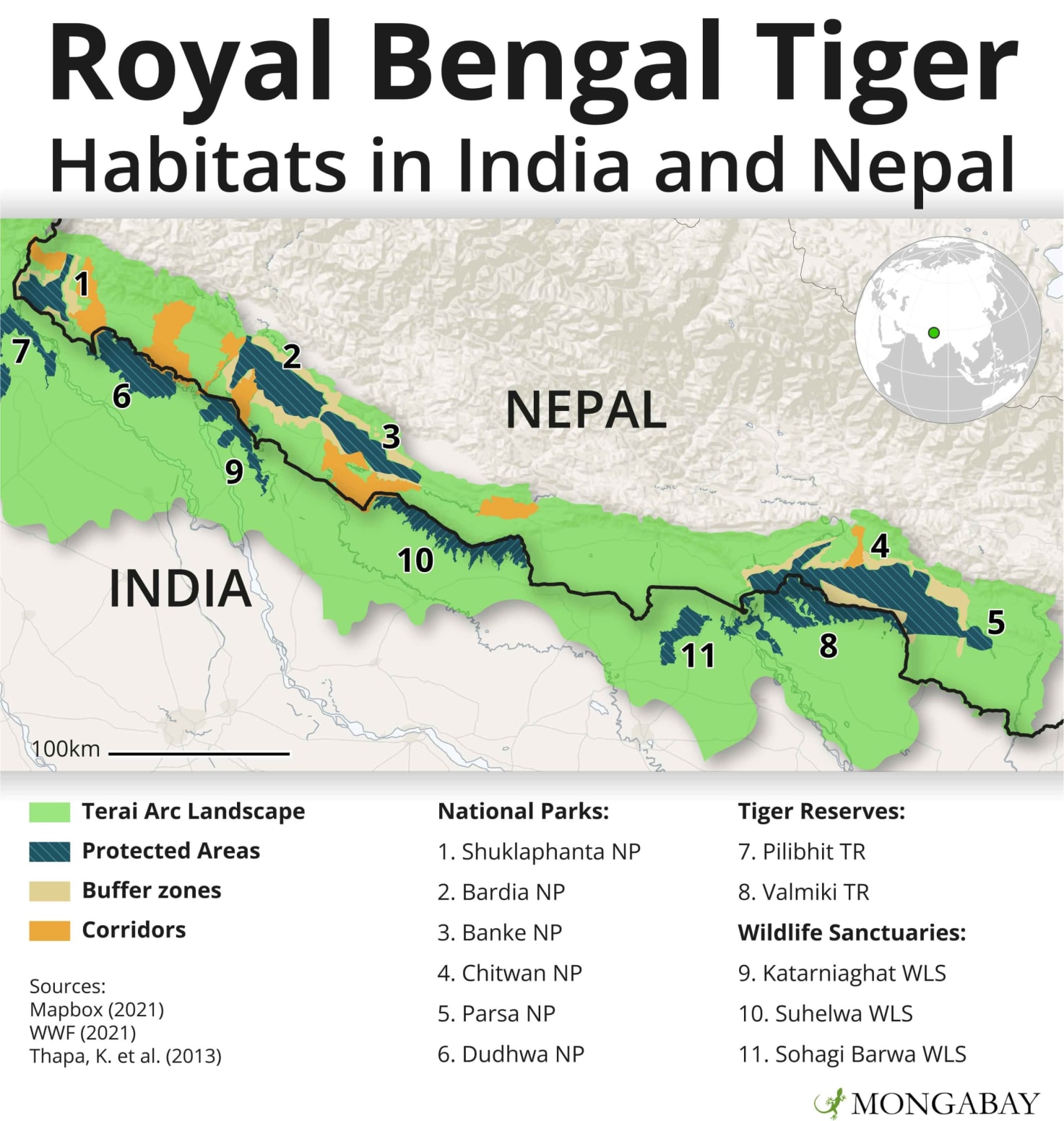

But the notion of “national” tigers was discredited in the late 1990s when conservationists realised that conserving tigers in isolated protected areas would never be an adequate strategy. A study commissioned by the Save the Tiger Fund and conducted by WWF and the Wildlife Conservation Society developed a new approach for tiger conservation. They came up with the idea of tiger conservation units, habitat blocks across the tiger’s global range with the best potential to recover and secure their populations. The TCU analysis originally identified six units across south-central and western Nepal and northwestern India.

These units were separated from one another by degraded habitat that was likely a barrier to tiger dispersal. It was agreed that conservation efforts should focus on creating habitat connectivity between these six TCUs by restoring forest habitats and corridors to facilitate the tigers’ movement. This would result in a large and connected landscape extending from Nepal’s Bagmati River in the east to India’s Yamuna River in the west, called the Terai Arc landscape.

In recent decades, rapid human population growth and land-use change, especially the building of new roads, in this landscape have led to deforestation and expansion of human settlements.

This means that wildlife that could historically move from one country to another along the 1,850-kilometer border are now limited to a few corridors that run across it (prominent among them are Boom- Brahmadev, Shuklaphanta – Lagga-Bagga-Tatarganj-Navadia, Laljhari, Basanta, Khata and Chhedia corridors).

These corridors connect key tiger habitats such Pilibhit in India with Shuklaphanta in Nepal; Dudhwa with various community forests in Nepal; and Katerniaghat with Bardiya National Park, says Pranav Chanchani, national lead for tiger conservation at WWF-India.

Contemporary use of most of these corridors by tigers has been recorded — barring Boom-Bhramadev and Chhedia where information is lacking. “Information from a radio-collared tiger in 2018 revealed that tiger movement between the two countries is not merely limited to these corridors but also occurs through agricultural areas and small forest fragments connected with Nepal’s Churia range,” Chanchani said.

Some corridors have already been affected by Nepal’s roads; their effect on tiger movement has yet to be ascertained, said Lamichhane. Although Nepal recently issued a set of guidelines for the construction of wildlife-friendly infrastructure, these are not yet fully implemented. Similar border roads are being built in India.

A recent study suggests that when roads run close to protected areas, wildlife is threatened not just by being hit by vehicles. They also face the fragmentation or loss of their habitat, reduced genetic connectivity, and increased poaching. The new border roads being planned in both countries could have deleterious impacts on tiger movement and ultimately the species’ survival unless appropriate mitigation structures are expediently built, Chanchani said.

As the human population increases on the fertile plains, vehicle traffic is expected to pick up on these roads, increasing the risk for the endangered animals. Prachi Thatte, who studies connectivity conservation genetics at WWF-India, said genetic studies on tigers reveal that high-traffic roads act as barriers to their movement.

“Even the existing national highways connecting major city centres may be permeable to tiger movement on stretches with low traffic volumes and when other landscape features facilitate movement. This is corroborated by data from radio-collared tigers that have been observed to cross national highways at night when the traffic is low,” Thatte told Mongabay-India.

While roads with moderate to low traffic are not complete barriers, they do obstruct gene flow, likely due to the risk of death. “Although tigers are currently known to navigate across low-traffic roads, this is bound to change in the future as traffic is projected to increase and roads will likely be widened to accommodate increasing traffic volumes,” Thatte added.

A 2018 report by India’s National Tiger Conservation Authority recommends that roads being built along the border with Nepal avoid traversing protected areas and corridors and ensure appropriate and adequate animal passageways where alternate alignments are not possible. But the recommendations from the report haven’t been fully implemented, as both countries continue to build roads.

Less tangible barriers are people’s attitudes towards tigers in corridors.

“Where tigers are less tolerated, or poorly protected they may not be able to disperse successfully through corridors because they are driven back, injured or killed. Finally, in areas like Suhelwa where forests between India and Nepal are still contiguous, animal movement may be constrained on account of numerous settlements along the border, with most being located at or near vital water sources,” Chanchani said.

Despite its ecological importance for the long-term survival of wildlife, especially the tiger, Suhelwa is under threat primarily from illicit timber smugglers (felling of khair or Acacia catechu trees), who carry out organised fellings in a well-planned manner, according to Sujoy Banerjee, Indian Forest Service Officer posted in Gonda in Uttar Pradesh. Surrounded by 100 villages, Suhelwa also has high human pressure.

Improved protection has resulted in the presence of tigers after almost two decades in a camera trapping exercise carried out by the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun.

“Most of the habitual offenders (illegal loggers) have been arrested and the Gangster Act slapped on them with due cooperation of the police of Balrampur and Shrawasti districts. We also have illicit fellers and poachers crossing the border from Nepal. Quite a few such offenders have been arrested and booked in a joint operation of the forest department and Seema Suraksha Bal (SSB),” Banerjee told Mongabay-India.

Tigers have even been found crossing rivers such as the Sharda (known as the Mahakali in Nepal) to move between the two countries. “In one of these corridors between the Boom Range of Champawat Forest Division in India and Brahmadev in far western Nepal, tigers swim across the Sharda river for many months of the year, barring perhaps in the rainy season,” Chanchani said.

Tiger movement has also been recorded in small sections of farmland in the Lagga Bagga-Shukla Phanta corridor, where the forests and grasslands of India’s Uttar Pradesh state meld into the Shukla Phanta Wildlife Sanctuary of Nepal, with the Sharda River looping around in the south and southeast.

But as farming areas see a rise in the unplanned building of infrastructure, it may not be easy for tigers to continue taking this route for long, experts say.

While there’s value in looking at the transboundary landscape as a single unit in conservation action — to harmonise planning and interventions for transboundary landscapes — differences in forest management and governance across countries make it challenging for combined efforts, conservationists say.

A transboundary approach to conservation has been adopted in the TransBoundary Manas Conservation Area, and to an extent, also in the Terai Arc landscape.

“However, given the differences in forest management and governance, security and development imperatives, and social, economic, cultural and political settings across international borders, it has not always been possible to align all relevant aspects of conservation programs,” Chanchani said.

Despite the challenges the Bengal tiger faces in crossing between Nepal and India, conservationists on both sides of the border agree that the fates of the animal’s populations in both countries are intertwined, as is the well-being of the people living in the frontier region.

This makes International Tiger Day this July an opportunity for the range countries to look beyond population growth, said Narendra Man Singh Pradhan.

“We should look at the landscape as one unit and come up with concrete efforts to facilitate the movement of tigers between borders,” he said. “We have no other option.”

This story was first published in Mongabay India